“Now, Peter Stothard has given us the final decades of the republic through the eyes of Crassus—Rome’s wealthiest man and former consul who famously embarked on a vainglorious and ultimately failed conquest of Parthia that culminated in his embarrassing death.”

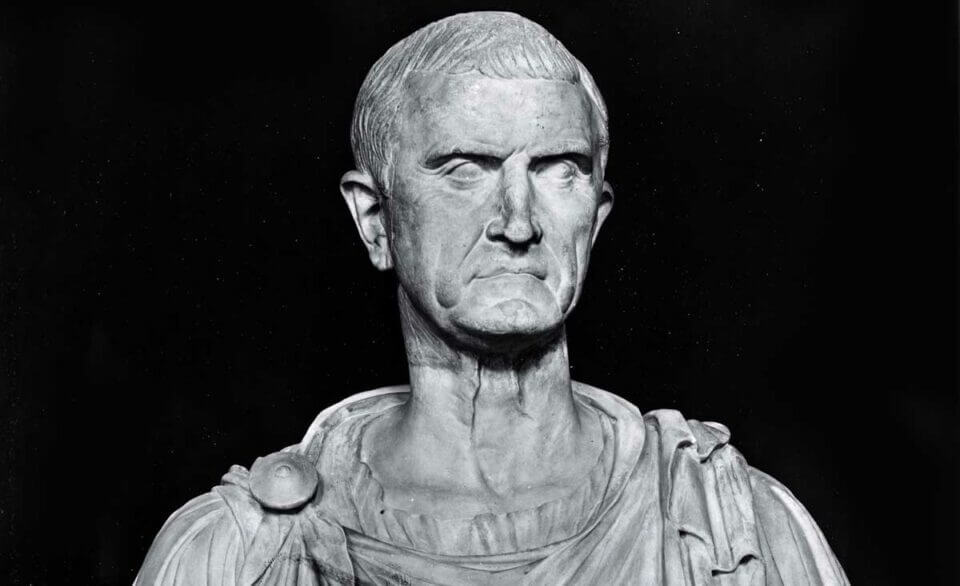

“The first tycoon of ancient Rome was also its most famous loser. If Marcus Licinius Crassus had died in 54 BCE he might have quietly entered history as Rome’s richest man, its first modern financier and political fixer…His modern face would have been from 1960, Laurence Olivier in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.” If people still know the name Marcus Licinius Crassus, it is, indeed, from Olivier’s portrayal of the Roman tycoon and general from Kubrick’s epic film. Perhaps a few others have read his name in passing from books on the fall of the Roman republic. But few have any intimate knowledge of a man who was once the rival of Julius Caesar and Pompey during the nadir of the republic, a name that all of Rome knew well in the republic’s final decades.

A millennia and half after the life of Crassus, Petrarch remarked that history was but the praise of Rome. While praise of Rome has fallen on hard times as of late, Rome still sells well and is open for business even at the places that also want to extinguish the light and flame of the eternal city perched on those seven Italian hills. There has been no shortage of recent histories of Rome, the end of the republic, and the birth of the empire under Augustus. What has proliferated in the past two decades of these never-ending Roman histories and biographies is the story told from new perspectives. This we can, and should, be thankful for.

We are all familiar with the fall of the republic from the eyes of the immortal names of Caesar, Augustus, Antony, and Cleopatra. Now, Peter Stothard has given us the final decades of the republic through the eyes of Crassus—Rome’s wealthiest man and former consul who famously embarked on a vainglorious and ultimately failed conquest of Parthia that culminated in his embarrassing death.

The fact that a biography of Crassus did not exist for popular readership has been corrected by Stothard. We wonder why it was not done sooner. Crassus’s life coincides with all of the great luminaries, once formerly famous, still famous: Marius, Cinna, Sulla, Julius Caesar, Cicero, Pompey, and Spartacus. During the tumultuous years as the republic failed and the march to dictatorship and empire commenced, Crassus found himself in the thick of the maelstrom and emerged as one of its great victors before his own greed—per Plutarch—eventually betrayed and killed him.

But the rise and fall of Crassus ran through the chaos of the final decades of the republic. His father was killed, and Crassus had to flee to Spain during the height of the populist tyranny of Marius and his supporters. By the time he was in his 20s, “he had seen politics at close quarters since he was a boy.” Witnessing brutality, murder, and scheming, Crassus was resolved to build his own fortune in a subtler manner. Acquiring run-down and decaying manors, he rebuilt them and rented them out to curry favors. He built his own private empire on social trust and financial loans to those in need but also to those who would be useful allies in the future. “Crassus took a more businesslike approach” to politics and social scheming than the murder politics with which he had been previously familiar. After all, even the winners in that latter situation did not seem to last long.

By the time Crassus became an important subordinate to Sulla, changes were brewing in the east that would garner the attention of the great men of Rome. The heirs of Alexander had been decimated. The rise of peripheral kingdoms such as Pontus and Parthia would attract would-be conquerors and saviors of which Pompey became the most famous. Eventually, the great power of Parthia became the thorn in Rome’s side that would lead to Crassus’s desert expedition as a means to rival Pompey and to keep the ambitions of Julius Caesar in check.

The uniqueness of Stothard’s account of the tumultuous final decades of the Roman Republic is in a new east-west narrative in which we see the inner workings of Rome as well as the vibrancy—however brief in the narrative—of Parthia. Most readers will not find new details about how the last years of the Roman Republic unfolded; but many readers may discover new things about how Parthia was (and about how Parthians were perceived by Romans). Though brief, Stothard’s little biography of Crassus offers glimpses into other great civilizations and peoples during the first century B.C.

The Parthians were not a reincarnation of the Persian Empire, as is sometimes imagined. The Parthians mixed Greek with their native tongue. They adopted Greek customs and drama, while retaining their own customs. Greek-style coins were minted and used throughout the expanding Parthian Empire. In defeating the Greek Syrians (the Seleucids), who claimed the heritage of Alexander the Great, the Parthians claimed the legacy of Alexander for themselves. Parthia was a hybrid culture; it was a vibrant multicultural polity that attracted the simultaneous admiration and scorn of the Romans.

It was this vibrant mixed civilization off in the east that drew Crassus, who had managed to survive and thrive through the Marian civil wars, Sulla’s restoration, and the Catiline Conspiracy. With the Roman Republic devolving into a three-man power struggle, Crassus had to pursue something that he only faintly tasted in his earlier years: military glory. Although he defeated and crucified Spartacus, the fact that Crassus’s greatest military achievement was fighting slaves did not bode well for him. Pompey had conquered the lands of the east, including Jerusalem. Julius Caesar was conquering Gaul and winning much praise. And even Crassus’s son, Publius, was making a name for himself as a daring cavalry commander in Caesar’s army.

The limits of wealth forced Crassus into military action. Even though he “was at the height of his power and hopes for more power,” the Roman tycoon needed more. Crassus needed the military glory that Pompey had won, Caesar was winning, and that was eluding him. So he assembled his private army and marched east, determined to upend Pompey and win more glory than Caesar in order to become the undisputed “first man” of Rome. Then Crassus, along with his son, Publius, met their demise in the desert sands near Carrhae in one of the worst defeats in Roman military history.

Traditionally, a failure in battle by a Roman general could be forgotten through a heroic death. Even in defeat, a Roman could win glory for how he died. Even this glory eluded Crassus. Having already lost his son and seeing his head on a spear, taunted by the Parthians during the height of the battle, the tired and exhausted Crassus agreed to a peace negotiation with the victorious Parthians. Mounting a horse to ride back to the Parthian camp, a brawl ensued. When the dust settled, Crassus was dead.

Crassus: The First Tycoon is but another piece of evidence that long after the fall of the Roman Republic and Empire, the story of Rome remains an eternal topic—the best evidence of the eternality of the city. Although countless histories of the fall of the republic have been written, this latest entry is a brief window into that collapse from the eyes of a man who was once so important but largely forgotten—mainly because he never achieved that conquering immortality of Pompey and Caesar. Stothard tells that story of how Crassus managed to become Rome’s richest man in the republic’s final decades but having never obtained the military honors of his rivals, Crassus’s pursuit of that glory—traditionally told as a continuation of his material greed—led him to an ignominious death and, ultimately, the trash heap of (mostly) forgotten history.

Paul Krause is the editor-in-chief of VoegelinView. His most recent book is Finding Arcadia: Wisdom, Truth, and Love in the Classics. He can be found on Twitter @paul_jkrause