Do some classical liberals and libertarians have more in common ideologically with the alt-right than they’d like to believe?

Introduction

There has recently been a swath of commentary noting the strange connection between those who initially identify as “classical liberals” or “libertarians”—particularly in online forums—and a gradual transition of these individuals toward holding alt-rights views. Sometimes called “the classical liberal pivot,” the conflation of classical liberalism and libertarianism with alt-right positions has naturally drawn the ire of many who identify with the former two. And as I shall explain, apologists are correct to contend that critics are making a serious error when they conflate classical liberalism and libertarian theory with the positions of the alt-right. Nevertheless, it is worth examining why many who do adopt this labels do paradoxically seem to gravitate towards post-modern conservative reactionary positions. This includes figures like Stefan Molyneux, who originally identified with libertarianism before going on to peddle white nationalist and misogynistic rhetoric, and Paul Joseph Watson, who also made the shift towards putting forward far-right conspiracy theories. The issue has become serious enough that classical liberal and libertarian leaning organizations such as the Foundation for Economic Education and the magazine Reason have admirably sought to distance themselves from the alt-right.

In this essay, I will contend that the roots of this inclination lie in the two ways that individuals tend to interpret classical liberalism and libertarianism. The first is truer to the roots of liberal thought in stressing the moral equality of all individuals. These figures, who are often highly critical of the alt-right, associate with classical liberalism and libertarianism because they fundamentally believe that all human beings should be free to live as they choose without being subject to coercion by political authorities. The second way individuals tend to interpret classical liberalism and libertarianism is as an ideology which is strictly inegalitarian. They tend to support it because they see society as a competitive association, where superior individuals will rise to the top due to their merits and efforts. While they identify as classical liberals and libertarians, these individuals tend to limit themselves to desiring a capitalist marketplace to discriminate between the superior and inferior by allocating rewards and honors according to economic contributions. But if these individuals come to believe the system increasingly rewards the unworthy, they can be inspired to radicalize and move further to the extremes offered by alt-right doctrines.

Classical Liberalism and Equality

The first set of individuals follow the inclinations of Will Kymlicka in regarding the “moral impulse” of liberalism as stressing the fundamental equality of all human beings. This impulse arguably goes back to even pre-liberal thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, who in the Leviathan stressed that in a state of nature human beings were functionally equal in their capabilities and value. It goes on through the work of Kant, who stressed that each human being possessed a dignity which placed him “beyond price”—and J.S Mill, who argued that the state had no business deciding what kinds of lives or doctrines free individuals should live by. Each person’s decision about how he or she was going to live a life was to be granted equal status by the law, except, of course, where such might might“harm another.”

Liberal institutions reflected these tensions, accepting ongoing discrimination against women, ethnic and racial minorities, and LGBTQ individuals for much of their history. These were appalling examples of hypocrisy which many have rightly criticized. But generally speaking, liberalism’s story has been one of granting more and more equal moral weight to all individuals from different walks of life.

In the present day, classical liberals like Milton Friedman and libertarians such a Robert Nozick largely agree with these positions. In his great work Anarchy, State, and Utopia, Nozick hypothesizes about a future where a “minimal state” exists and individuals are free to experiment with as many different forms of life as they choose. This may even include communist or socialist communities, where individuals would willingly choose to share property in common and live according to more egalitarian principles of distributive justice. But no one form of life would be enforced by political authorities, which had no business telling free and equal individuals what the best way to live was.

Of course, there were many deviations and setbacks to this moral impulse, even within liberalism itself. Many classical liberals who agitated for more egalitarian outlooks still made exceptions for large swaths of the body politic. Locke was famously critical of the pretensions of monarchists, but he was far less concerned about achieving equality for slaves and Native Americans. Kant and Mill both held racist and imperialist attitudes, even where they ran contrary to what was best in their philosophical positions. As Quinn Slobodian observed in his excellent book Globalists: The End of Empire and The Birth of Neoliberalism, Ludwig von Mises was a fierce opponent of state coercion in most circumstances. But he was willing to flirt with exceptions where violence was “necessary” to buck the power of unions and socialists—for instance during the Vienna Strike of 1927. And, of course, liberal institutions reflected these tensions, accepting ongoing discrimination against women, ethnic and racial minorities, and LGBTQ individuals for much of their history. These were appalling examples of hypocrisy which many have rightly criticized. But generally speaking, liberalism’s story has been one of granting more and more equal moral weight to all individuals from different walks of life.

For the set of individuals who identify with this interpretation of classical liberalism and libertarianism, the moral equality of all is the starting point for politics. This means that each person is taken as possessing an equal value commensurate with human dignity, common humanity, and so on. Needless to say classical liberals and libertarians, in this vein, do not intend this to mean that the moral equality of individuals requires intervention to secure greater economic equality for all. Many of the debates among classical liberals, libertarians, and liberal egalitarians and social democrats like John Rawls and Martha Nussbaum (which I have analyzed here) concern exactly this point. For Rawls, Nussbaum, and I, for that matter, the moral equality is not respected where substantial and arbitrary economic differences between individuals are allowed to persist.

At minimum, a just and fair society must take steps to ensure a largely equal baseline of skills and resources for all before one can even talk about justifiable inequalities in economic outcomes. We also tend to believe that this is valuable because it not only better respects the moral equality of individuals, but it will ultimately enhance their freedom. Contemporary classical liberals and libertarians, who also believe in the moral equality of individuals, disagree with this push for greater economic equality.

There are, of course, a variety of reasons for this. Some, like F.A Hayek, stress that any efforts to try and change the capitalist system will only lead to economic instability and ultimately make everyone worse off, including the very poor. Others, like Nozick and Friedman, tend to believe the same. But they also make a moral argument that appropriating resources from individuals who engage in free economic transactions constitutes a serious infringement on their liberty. This cannot be tolerated, in part, because morally equal individuals are entitled to have their economic choices respected, which cannot occur if they are manipulated by state authorities, who feel they know better where resources should be directed. To not respect them is, in part, to treat individuals like slaves who work in the service of another’s vision of greater economic equality for all. At base, the perspective of these classical liberals and egalitarians is that it is the state which poses the greatest threat to respecting the moral equality of all.

This debate has gone on for a long time, and I do not intend to rehash its nuances at length here. It is suffice to say that the moral differences between individuals who hold to this interpretation of classical liberalism and libertarianism—and their liberal egalitarian and social democratic opponent—are comparatively minimal. All agree that each individual possesses an equal moral worth. The debate and conflict is then over how this moral principle is best realized. Is it through a minimal state characterized by modest or non-existent efforts to redistribute resources—or is it through a more social democratic state which aspires to greater economic equality? The differences are obviously significant, but they pale in comparison to individuals on the far-right who hold to very different moral principles.

Inequality and the Far Right

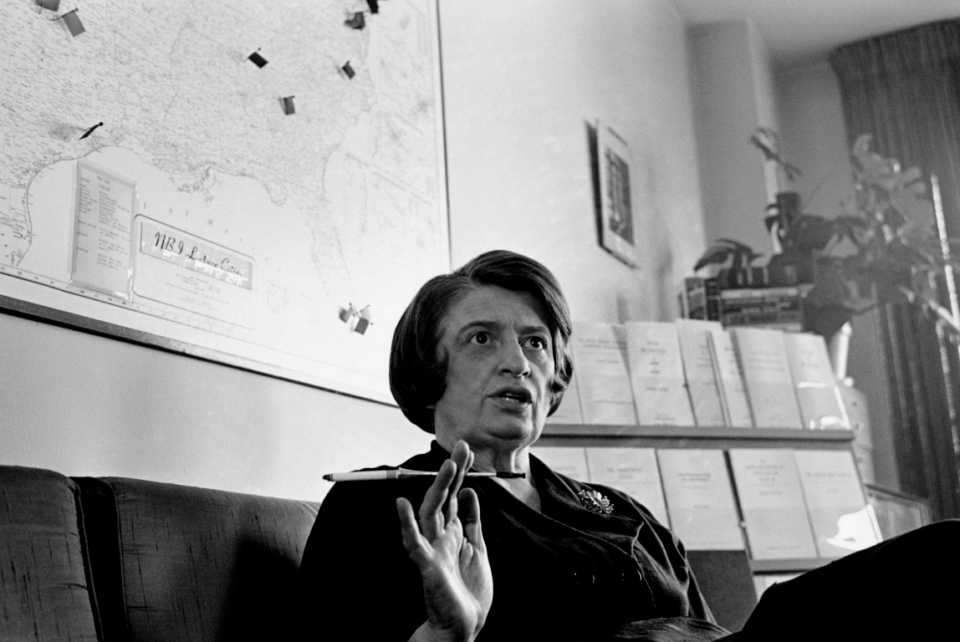

Individuals who associate with the second interpretation of classical liberalism and libertarianism may hold many of the same views as their peers in the first camp. But the basic moral principles they adopt are quite different. For these figures, society is fundamentally a hierarchical and competitive association which should be characterized by what Ayn Rand called “superior” individuals rising to the top. This, in turn, makes them attracted to capitalism as an economic system, which seems to situate figures where they belong, based on their individual merits and contributions. As time goes on, the more numerous and less meritorious will fall to the bottom, and the “superior” will rise to the top. Now, according to these figures, such an arrangement will be mutually beneficial for all, since the rewards and honors accrued by superior people are the result of what they’ve contributed. Everyone benefits through the efforts of heroic individuals who create new products and institutions which improve the quality of life for all. But, that is not the primary virtue of classical liberalism or libertarianism for individuals in the second camp. It is at best a secondary virtue. The reason why they support classical liberalism and libertarianism is because it establishes the proper hierarchy needed for the smooth functioning of a well-ordered society. Figures like Dinesh D’Souza stress these doctrines because they (falsely) see them as generating unequal results for fundamentally unequal people and cultures.

The problem these figures often run into is that the “moral impulse” of authentic liberalism will always lead to substantial criticisms of inequality within liberal-democratic societies. Even classical liberals and libertarians in the first camp can be persuaded on these points, which is partly why figures like Milton Friedman supported earlier iterations of the universal basic income project. More radically, there are liberal egalitarians and social democrats who argue that the capitalist system is too prone to rewarding individuals for morally arbitrary reasons—for instance penalizing those who are born into poor families versus those who inherit substantial wealth from their families. They will also point out that the discriminatory practices characteristic of earlier liberal societies, for instance the prejudice directed against women and ethnic minorities, continues to have an impact on those groups. A consistent liberalism would need to take steps to ameliorate these problems through, for instance, affirmative action programs.

These positions are obviously noxious to individuals who support classical liberalism or libertarianism because the political adoption of these doctrines generates a social hierarchy with the superior on top and the inferior further down. They resent any efforts by liberal democratic societies to ameliorate real or perceive inequalities, since this is typically done by granting artificial advantages, which enable the less worthy and undeserving to climb to a social rung where they do not belong. If they see this happening too frequently, these individuals may begin to lose faith in liberal institutions and believe that more radical political positions are necessary. This is where the arguments offered by the alt-right can seem increasingly attractive. They propose to use state power to eliminate those calling for unjustifiable and vulgar equality—and to entrench the authority and status of those who are more worthy. Over a sufficiently long period of time and through a process of ideological normalization, these formerly classical liberals may come to embrace more post-modern and reactionary viewpoints.

Conclusion

My point in this brief article was, of course, not to condemn the first interpretation of classical liberalism and libertarianism. While I have substantial disagreements with these positions, they accept the premise that all individuals are morally equal. Our disputes concern how to go about realizing that principle. This is a different interpretation than those given in the second camp, which reject the moral equality of all individuals. In their mind, the chief virtue of classical liberal and libertarian doctrines is their characterization of society as a competitive association where unequal people end up with highly unequal life outcomes. If these individuals lose faith in liberal democratic institutions, it is because they feel they are too prone to rewarding the unworthy by granting them artificial advantages they do not deserve. In such circumstances, the more radically inegalitarian doctrines of the alt-right can look exceptionally tempting.

Matt McManus is currently Professor of Politics and International Relations at TEC De Monterrey. His book Making Human Dignity Central to International Human Rights Law is forthcoming with the University of Wales Press. His books, The Rise of Post-modern Conservatism and What is Post-Modern Conservatism, will be published with Palgrave MacMillan and Zero Books, respectively. Matt can be reached at garion9@yorku.ca or added on Twitter via Matt McManus@MattPolProf

“Needless to say classical liberals and libertarians, in this vein, do not intend this to mean that the moral equality of individuals requires intervention to secure greater economic equality for all.”

Not true. Classical liberals and early (Georgist) libertarians advocated the Single Tax.

“At minimum, a just and fair society must take steps to ensure a largely equal baseline of skills and resources for all before one can even talk about justifiable inequalities in economic outcomes.”

This seems to be a version of the Rawlsian original position, with which classical liberals should have no truck. Instead, without the need for such abstractions, I suggest that those who have acquired wealth through proper means, enterprise or lawful inheritance, have a moral obligation to dedicate some reasonable portion of that wealth to preventing, or at least ameliorating, destitution.

They are so obliged because: a) destitution in the midst of prosperity is prima facie an offence to equal moral worth; b) their prosperity was acquired, directly and indirectly, from the labour and spending of the mass of the people; c) raising people out of destitution enables new entrepreneurs to flourish, to the good of all; d) the peace and order on which free enterprise and inheritance depend is threatened by such destitution.

There is no need of veils of ignorance; enlightened self-interest is much preferable. In practice, of course, governments have to intervene, partly as just enabler, and partly to prevent freeloading.