On the current trend towards drug liberalization: “Everybody I know who functions at a high level in society is fairly reliable and trustworthy. My husband is an oncologist, and I can tell you that hardworking cancer doctors don’t spend their free time getting high.”

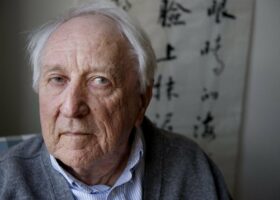

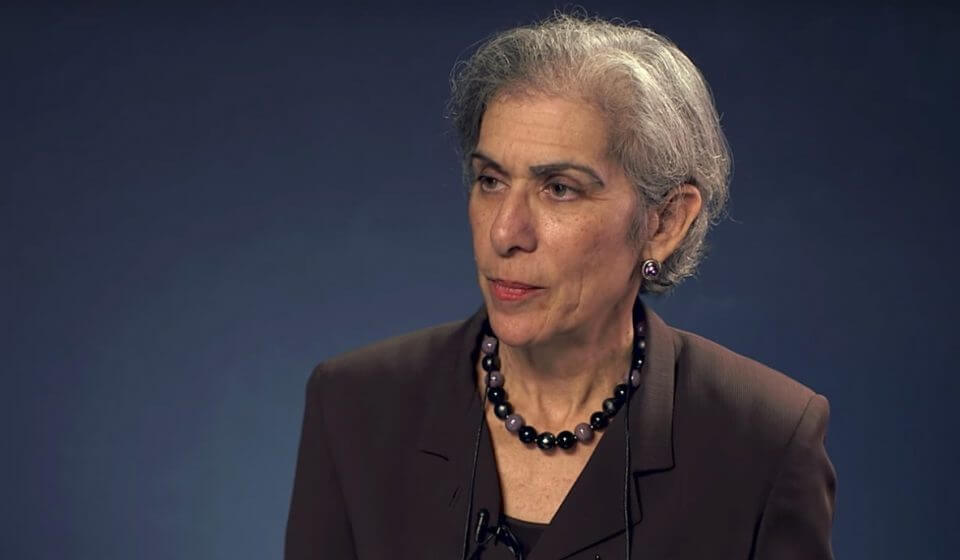

On February 13th, Professor Amy Wax of the University of Pennsylvania school of law joined Merion West‘s Erich Prince to discuss her controversial Philadelphia Inquirer op-ed on the decline of traditional values in American society, the backlash she received from colleagues and students, drug policy, and the state of conservatism in America today.

Thank you, Dr. Wax for being with us today. To begin, could you talk a little bit about the op-ed you wrote for The Philadelphia Inquirer and how you chose that publication as your outlet to share your views on the”breakdown of the country’s bourgeois culture?”

It was an accident more than anything else. My co-author, Larry Alexander, whom I’ve known for many years, asked me if I would participate or co-author this piece with him. He sent me the piece about the loss of bourgeois value because I did some editing of it. I said “okay, I’m willing to go in with you.” I sent it to an editor I knew at The Philadelphia Inquirer, and he said we’ll publish it. I thought very little about it at the time. It was the dog days of summer, August 9th. I all but forgot about it until this conflagration greeted me.

And it was shortly after August 9th that The Daily Pennsylvania, the University of Pennsylvania’s student newspaper, began to cover some of the responses to your op-ed?

A lot of different groups on campus made statements and issued condemnation, and some of them ended up in The Daily Pennsylvania. Some professors from Drexel and Temple signed a letter. A lot of the stuff ended up online. Then there was a column signed by five of my colleagues accusing me of doing bad history because of my praise for the 1950s and for some of the cultural scripts of the 1950s. I read that and didn’t really agree with it, but I thought “well, this is fine.”

I think when things really went south was when one of my colleagues, Jonah Gellbach, took it upon himself to write a letter of condemnation and a sort of categorical rejection of all my views, including an interview I gave the next day with The Daily Pennsylvania after my column appeared. He got 32 of my colleagues to sign it without really explaining why they condemned what I said or what precisely they were condemning. They also invited the students to report bias and discrimination, obviously coupling it with a condemnation of me. The implication was they that they could expect that kind of treatment from me. It was really just a lot of innuendo

Did you feel as though some of the criticism seeped beyond your arguments and views to you personally?

No, it’s not that it was personally directed. It’s that there were no arguments and no rationale. It wasn’t academically-reasoned discussion. It was just a blanket condemnation, and I took great umbrage to that, primarily not so much because it was a personal attack. I think, though, it was meant as a personal attack, but because I thought the form of discourse [my colleagues were using] set a terrible example for the students, whom we are trying to teach to analyze arguments, provide counter arguments, counter evidence, reasons and examples. [My colleague’s responses] had none of that. I found that very alarming

How emblematic do you think your experience is of the times in which we’re living? Do you think that the academic discourse has devolved since you began teaching? Has it always been this hostile towards more right-leaning views?

No, it has not always been this hostile. When I was an undergraduate at Yale in the 1970s, it was nothing like this–absolutely nothing like this. People differed sharply on many political matters and other issues. The Vietnam War was winding down; there was a lot of disagreement, but the discourse and the interaction was far more civil.

People felt the need to back up and justify their points of view. Their positions were not anywhere near as moralized and as polarized as they are now. This whole lexicon, this mindless name-calling of sexism, racism, white supremacy, xenophobia, homophobia – this little recitation that now has become a routine ritual on campus as a substitute for thought, had not really caught on. Now it’s the eight-hundred-pound gorilla that just eats everything.

In response to some of these concerns, universities are talking about how there should be almost an affirmative action effort to get more conservative professors at universities. For example, Yale, our alma mater, makes efforts to recruit professors who are ethnic minorities. Is an ideologic affirmative effort a worthwhile project or do you think that it’s almost inherently “unconservative” or problematic in its own right?

I don’t have a theoretical objection to it, although these kinds of efforts never really work. On a practical level, I’m not sure where this effort is going to be coming from. I mean first of all, the academy has become so utterly progressive and locked-in that I’m not even sure that they could do it correctly. Many are not even familiar with basic conservative positions and arguments.

They are oblivious to the positions, so they have almost zero understanding of what it is they’d be extending affirmative action to. Also, we have a tremendous pipeline problem; conservatives just don’t go into academia because they know they are not welcome.

They are not, and part of the professoriate will overtly say we don’t need conservatives because their ideas are wrong; they are anti-scientific, they are racist or sexist, they are mean, they are destructive, and on and on. Routinely you will see letters in The New York Times explaining the fact that we don’t have conservatives by saying it’s because conservatives are stupid. How are you going to go up against that?

So you think it’s more of a self-selecting situation where more liberal people are going to academia in the first place?

There is a lot of self-selection, but also there’s an indoctrination process taking place that is massive. We have very impressionable and extremely under-educated young people, which is not to say they are not smart. They have the I.Q. points in many cases but they are just profoundly ignorant. They have also been subject to the K-12 system which is also captured by progressives.

They have been fed a lot of tendentious nonsense from a tremendous amount of anti-American, anti-Western views with diversity and inclusion ideology as catechism and gospel truth and also as being the only possible credible moral position. All of this ideology is hammered into them from an early age.

Once they get to college, the process is pretty much complete. There is a small and hearty band of people who stand apart from that and are skeptical of some of the empirical claims, which they know don’t hold water because these students are well-read. There’s a core of real intellectuals out there – smart people who have been raised to value conservative ideas, but they soon get overwhelmed. I think it’s very hard for them to maintain their open mindedness.

Also there’s another frightening phenomenon, which is that women are being totally dumbed-down by the current educational system. I think the quality of women’s ability to step back and analyze their degree of learning, the amount they read of ‘the classics’ and know about the important thoughts that have been thought in the past is declining.

Women don’t feel they need to read material from all those dead white males. They’ve been told that there’s nothing worthwhile in there. So I think the gap, in just plain old cultural knowledge between men and women, is broadening tremendously. I see it in front of my very eyes. My “conservatism seminar” is one woman and fourteen men. Our reading group here on the classics is overwhelmingly male. Our Federalist Society is overwhelmingly male. And what this means is that women are just taking themselves out of the running to be influential intellectuals in the future–unless they’re just sort of knee-jerk progressives.

Do you ever observe students coming in who already lean right and when they encounter this liberal aura at the University, they almost unthinkingly become more conservative–in a reactionary sense? The term “trolling” is applied often. But perhaps what’s really happening is that these conservative students are saying is: “I’m up against you, and I’m going to hunker down and be conservative no matter what” rather than engaging with opposing ideas?

Well, trolling is in the eye of the beholder. I think there always are people who think about things more or less deeply or adhere to their position more or less thoughtfully. That’s true on both sides of the political aisle. I don’t know such people.

I think there is a bit of backlash in reaction. Actually, Steven Pinker described it very well in his remarks praising the intellectual arm of the alt-right in his remarks for Spiked Magazine. I don’t know if you’re aware of what he said there, but it got some play on the internet where he said that the pall of orthodoxy in the academy, the extreme political correctness has frustrated, and in some respects radicalized young, evidence-driven, data-driven, wonky-type guys who are very interested in the progressive Left. They feel very resentful, and that can be a radicalizing experience, I think. However, my students here really aren’t of that sort. They do get frustrated. There’s a lot of eye rolling. And they recognize that they are being sold a bill of goods by the Left. But I don’t think they are mindless about it.

I guess we’ve spoken a lot about the backlash to your ideas so I just want to talk a little bit about the ideas themselves. I was reading your piece yesterday in which you were discussing “the pill” and the war in Vietnam. I’m wondering, since you talked a lot about the Vietnam War, to what degree do more recent events like the Iraq War further undermine and lead to more distrust of government? The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution as compared to “weapons of mass destruction.”

Well, I think the government has botched a lot of stuff through different administrations. That’s been something of a generic problem all along. We fought a just war in the Second World War and that made our government look really good. However, if you dig below the surface, they don’t look quite as good. Our cause was just, but we messed up some aspects. I think there is a generalized mistrust of government that runs as a tradition to our entire culture.

We do come out of a suspiciousness towards concentrations of power. “That’s our Anglo-American heritage,” as Jeff Sessions would say. But that’s sort of the broader picture. One of the problems is that government has become very big, very powerful, and very bureaucratic.

The administrative state has proliferated and burgeoned, and people really feel powerless in the face of this enormous mob. It’s also been captured by this pseudo-expert-hyper-educated elite class, which uses it to advance their cultural values, their priorities, their agenda, thereby exacerbating this sort of red state-blue state divide because the “Blues” dominate these positions of power.

But it’s not just the government–-it’s the media. It’s the universities. It’s what the dissident-right calls “the Cathedral.” There are a lot of different things going on. I think there is also the legacy of the 60s – the anti-traditionalism, the denigration of the celebration of libertinism, of bourgeois individualism, expressive individualists and the defiance of restraints, customs, norms, and mores that were accepted for a very long time. Even institutions like marriage are now sneered at, even though ironically, well-off educated people get married the most. There’s a lot of hypocrisy. “Limousine Liberalism” is a big problem. There are all these phenomena that feed into the divides in our society. It’s very complicated.

That leads me to our next question. Some of the people who are espousing libertarianism seem to be coming, at least in my view, from some of the same frameworks and types of arguments favored by the Left. Perhaps you disagree. But what type of influence do you think the libertarian movement has on conservatism. Libertarians and traditional conservatives might be in the same voting block, but they appear to emphasize different priorities.

Libertarianism, which is a minority faction within conservatism and primarily a young man’s game, has always been a niche phenomenon in American conservatism, although a very vocal one. But you’re right. They do share a common cause with the progressive Left because they enshrine and worship the individual choices and liberty and the ability to chart your own path and make your own way. “Don’t tread on me” and all of that.

The problem is, of course, that they emphasize different things. Libertarians emphasize economic liberty, while progressives emphasize sexual liberty and sexuality as the sort of the apotheosis of self-expression. [Liberals] really put a great deal of weight on sexual liberation, much more than it can bear in my humble opinion. But they are sort of kissing cousins. And I think they do feed into each other to the detriment of communal structures and norms and intermediating institutions that keep people in check. I think the fringe, the Bohemians can only exist because there’s a core of conventional, bourgeois people who pretty much plod along and do mostly what they were supposed to do. So there is a bit of parasitism here of liberated factions on the rest of us. You’re right. There are affinities though between parts of the Right and parts of the Left.

So you mention some of the longstanding institutions, and I remember in your op-ed you talk about Hispanic immigrants maybe not feeling the same urge to assimilate that they may have in the past. I was thinking about Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone. On that subject, what degree of influence do you think multiculturalism has on some of the social fabrics in the United States and Europe?

I think multiculturalism has come along at just the wrong moment. I mean it’s a really quite a corrosive and pernicious force just when we need sources of unity, core values and ideas and commitments that we can all get behind. A lot of this is due to the 1965 Immigration Act, which went terribly awry from its original purposes. Then it was paired with our lax attitude towards illegals, which is also fed from the right and the left.

In short-term interests, we need something to bring us together, and now we have this ideology that is dividing us into these squabbling tribes where we’re each trying to claim victimhood that is greater than the other group’s victimhood in order to divide up the goodies that are allocated to victims.

I can’t imagine where we’re going to end up on this path–-nowhere good. I see us sinking from first world-ism to third world-ism. The evidence is all around us and, of course, a lot of the evidence is evidence people don’t want to see. Really simple things: like the amount of litter on the street or noise levels, the degree of consideration for others, the restraints, giving thought to other’s interests, keeping up infrastructure, punctuality, honesty, trustworthiness, obedience to the law.

I always find it very ironic that one of the pillars of strength in our system, what makes us prosperous and peaceful and attractive and a hopeful society, is the respect for rule of law which, of course, is part of our Anglo-American heritage. Yet we have a whole group of illegals who have come here claiming to want to join our society, but they do it by breaking the law. I mean their first act is to break the law, and then to insist that we overlook that fact. That is deeply concerning to me, and I think it is horribly corrosive of the strengths of our society.

For the last question, I’d like to return to this issue of the libertarian influence on the Republican party. What are your thoughts are on the liberalization of drug policy in many parts the country, including marijuana in Philadelphia, and what sort of influence you think that might have on our social structures?

Well you know sobriety is a bourgeois virtue. Someone might ask why it is a bourgeois virtue. Now whenever you say that, people respond: “But we allow alcohol. We had prohibition and now we have alcohol.” As Jim Jacobs, a scholar at N.Y.U. has put it so eloquently: alcohol has a whole long many hundreds of years of tradition and set of structures that integrated into social life – in conviviality, in celebrations, in romance.

Rules for moderation and rules that limit the time and place of consumption, there are all sorts of conventions surrounding the use of alcohol. It’s really woven into our lives and our traditions in ways that these illicit drugs, for better or worse, are not. So you know what we’re doing is we’re comparing a deeply socialized set of conventions surrounding alcohol with essentially the Wild West.

What disturbs me is what’s going along with it, a denigration of sobriety as an important social value – the deep restraint that we need when we’re dealing with these substances. A person who studies addiction, a minority psychologist, a very high profile, hip guy who I met at a conference, when I told him “sobriety is a virtue and we can’t forget that,” he just sneered at me. He said “well, that’s a white value.” That’s just white supremacy. I said “well, if you think that, and if your people share that view, that’s a problem.”

You won’t really get away with that because everybody I know who functions at a high level in society is fairly reliable and trustworthy. My husband is a medical oncologist and a medical school professor, and I can tell you that the hardworking cancer doctors that he surrounds himself with don’t spend their free time getting high. And we count on them not doing that. We really do. So for them, sobriety is a virtue.

Thank you for your time this afternoon, Dr. Wax.

Thank you for having me.