“However, in his uncompleted sequel to The Lord of the Rings, The New Shadow, as well as The Silmarillion, Tolkien presented a different vision of human nature, one that is more realistic and more concomitant with his Catholic upbringing.”

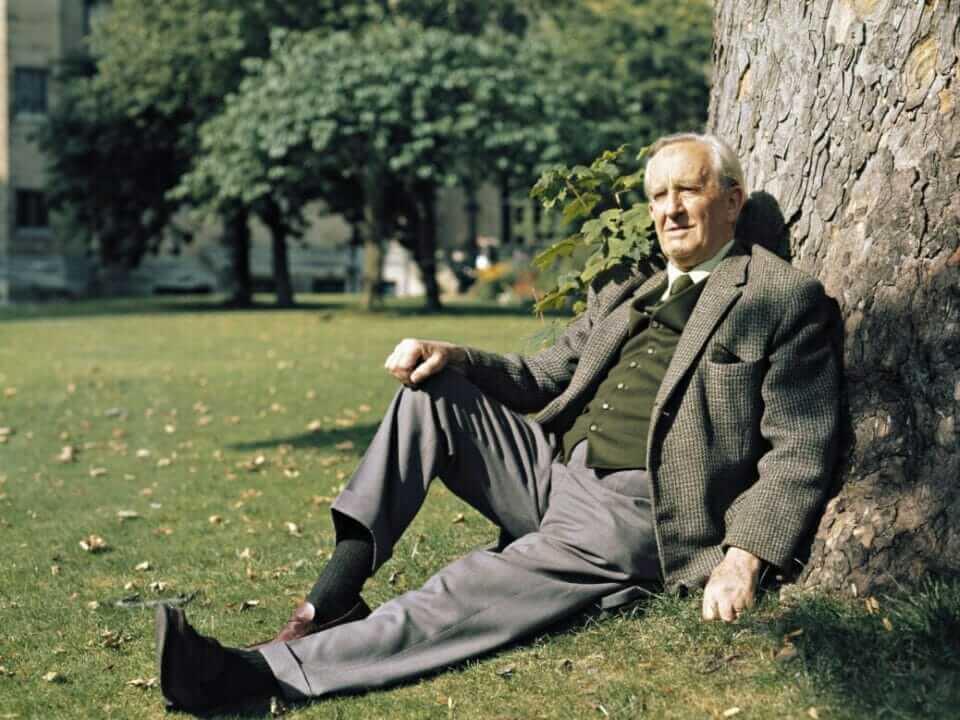

J. R. R. Tolkien would have turned 130 this month, and in spite of the apparent simplicity of his works, there are important lessons to be derived from his fantasy world. Tolkien’s oeuvre does not only teach us about the self-defeating nature of evil, the corrupting effects of power, the dangers of arrogance, and of the desire to impose order, however. For one of the recurring themes in Tolkien’s works is the human tendency to become satiated with good and cease to see evil for what it is.

In the fictional—and, in many ways, idealized—world of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit humans are taken to be inherently good, while evil is not part of our nature but is rather external, epitomized by the dark Lord Sauron and his ring of power, whose destruction leads to the triumph of good and prosperity in Middle-Earth. However, in his uncompleted sequel to The Lord of the Rings, The New Shadow, as well as The Silmarillion, Tolkien presented a different vision of human nature, one that is more realistic and more concomitant with his Catholic upbringing.

The Re-Emergence of “Shadow”

The New Shadow is set approximately a century after the events of The Lord of the Rings, near the end of the rule of Aragorn’s son Eldarion and is told from the point of view of Borlas, son of Beregond, one of the minor characters in the original trilogy. Borlas discusses the nature of evil with Saelon, one of his son’s friends, and then learns from Saelon that more and more people are becoming discontented with the state. Salon suggests that Borlas go with him to learn more about this, and Borlas decides to follow him, thinking that “[p]erhaps I have been preserved so long for this purpose: that one should still live, hale in mind, who remembers what went before the Great Peace. Scent has a long memory. I think I could still smell the old Evil, and know it for what it is.”

People of Gondor, having lived in peace for decades after the fall of Sauron, have forgotten the true nature of evil, for there always remain “some who will not be content, and to their life’s end they trouble their hearts about their neighbors, and the City, and the Realm, and all the wide world.” People tend to grow bored of good—and if we do not keep watch over evil, it will sooner or later reappear, just as it happened with Gondor when it abandoned its watch on Mordor and after the final fall of Sauron, which saw “an outcrop of revolutionary plots” and “rise of secret Satanistic religion.” Humans need a source of identity and meaning, and in the absence of a common national story, we begin to resort to modern-day cults like QAnon and other radical ideologies to make up this gap.

When there is no external enemy to fight against, a common threat that can unite people and thereby provide a clear perception of what is good and what is not, humans, with their inherent need for uncertainty and problems to address, begin to “invent” and overstate the severity of remaining social ills—a point I have made elsewhere. This explains why, following the end of the Cold War, polarization and animosity towards one’s political opponents began to rise in the United States—the absence of an external enemy redirected people’s “negative” energy and attention to “internal enemies.” Generations that did not live in times of true evil cease appreciating past achievements and the existing system, as they did not participate in its creation and did not sacrifice anything to defend it and, thus, do not value it as much as their ancestors did.

In a preface to the first edition of The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt wrote that “[w]e can no longer afford to…discard the bad and simply think of it as a dead load which by itself time will bury in oblivion.” Erasure of the memory of the true nature of evil will lay ground for its reappearance; it is no coincidence that the recent rise of the approval of Josef Stalin occurred at the same time as the Russian government had grown more repressive. In fact, according to some polls, half of Russians remain unaware of Stalinist repressions. In such an atmosphere, it should not come as a surprise that last month, a Russian court liquidated the country’s oldest human rights organization, Memorial, whose work focused on exposing victims of Soviet repressions, thereby ridding the country of a crucial element of the collective memory of the Red Terror.

Moving Beyond the Shire

In a letter from May 13, 1964, Tolkien wrote: “Since we are dealing with Men it is inevitable that we should be concerned with the most regrettable feature of their nature: their quick satiety with good. So that the people of Gondor in times of peace, justice and prosperity, would become discontented and restless.” This “inevitable boredom of Men with the good” Tolkien sees as an intrinsic characteristic of nature: “There are some enemies that such walls will not keep out.”

Tolkien’s distinctly Christian belief in a fundamentally flawed human nature, our tendency to grow “satiated with good,” which makes the re-appearance of evil possible, is present not only in The New Shadow. In Akallabêth, the fourth part of The Silmarillion, Tolkien recounts the story of the fall of Númenor, an ancient island country of humans endowed with long life and superior capabilities by the Valar as a reward for their help in the war against Morgoth, a primordial personification of evil. For a long time after Morgoth’s fall, the Númenoreans lived in peace and prosperity, but grew discontented as they began to desire immortality. And this eventually led to its fall.

One may think that this attitude contradicts Tolkien words in The New Shadow that the evil came with Melkor (later known as Morgoth), not because of inherent flaw humans: “Men did not come with these discords; they entered afterwards as a new thing direct from Eru, the One, and therefore they are called His children.” However, Tolkien’s disenchantment with his contemporary world, his resentment toward the industrialization of England, is a recurring theme in his work, especially the Shire in The Lord of the Rings, which is Tolkien’s conception of an ideal rural England that was lost in the past. There is, therefore, a conflict in Tolkien’s personal view (undoubtedly influenced by his Catholicism) of human nature as fundamentally flawed and his desire to wall off his fictional fantasy world from these negative influences, which may also explain why he decided to not finish The New Shadow.

The greatness of Tolkien’s works consists in the recurring relevance of the fundamental issues that he touches upon. In The Lord of the Rings, Samwise encourages his master, Frodo Baggins, saying that “[t]here’s some good in this world…and it’s worth fighting for.” In the age of resurgent relativism, believing in the existence of timeless truths for whose sake we can live—and sacrifice when necessary—is a way to provide meaning in our post-truth world.

A quotation often attributed to Edmund Burke reads: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” In Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, young and carefree hobbits have to leave the comforts and pleasures of the Shire to confront and ultimately defeat the growing threat of evil. Thus, only by active participation in public life can one contribute to keeping evil at bay—political amnesia and apathy of ordinary citizens is at the root of today’s polarizing culture dominated by fringe elements of the political spectrum. In order to prevent the shift of our perceptions of what is right and wrong that may occur, it is important to retain in our collective memory the recurring nature of evil and its true character: something Tolkien reminds us to do through his works.

Sukhayl Niyazov is an independent writer. His work has appeared in The National Interest, The American Conservative, City Journal, Foundation for Economic Education, Public Discourse, Law and Liberty, among others. He can be found on Twitter @Sukhayl_Niyazov and Medium @fallibilist