“However, dive a little deeper, and one finds a curious form of expression that—for all of its subversion of the law and public morality—was just as vibrant and popular as the subjects being parodied.”

In 1967, the underground satirical magazine The Realist published an infamous image at the behest of its founder, Paul Krassner. Bluntly called the “Disneyland Memorial Orgy,” this irreverent illustration by comic artist Wally Wood gained notoriety for its crass portrayal of Walt Disney’s characters, its publication shortly after Disney’s death, and its subsequent piracy over the decades that followed. Nevertheless, its publisher’s criticism of the emerging censorious threats copyright policies posed to creative liberties remains even more relevant today, especially when it comes to what constitutes “fair use.”

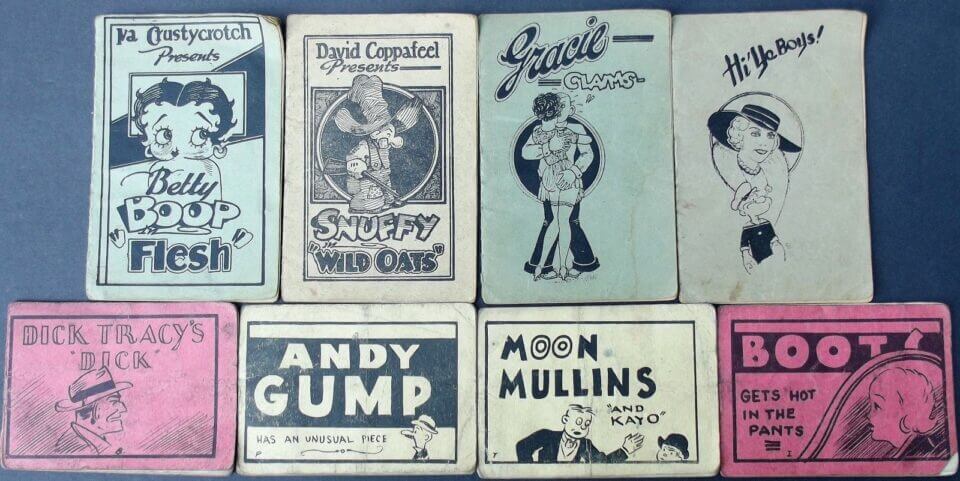

Worth highlighting, however, is how this piece of art was also an homage to a peculiar piece of Americana that, by then, had taken its last breath. Known over the years by terms as varied as “bluesies,” “jo-jo books,” “eight-pagers,” and, eventually, “Tijuana bibles,” these relics were independent comic booklets that flew in the face of intellectual property. Often parodies of established works and illicitly sold, their infamy stemmed from the parodies’ explicit nature. If they are remembered at all in common discourse, it is all too easy to brush such works aside as a raunchy footnote in history.

However, dive a little deeper, and one finds a curious form of expression that—for all of its subversion of the law and public morality—was just as vibrant and popular as the subjects being parodied. It is a story that crosses paths with various events in American history and the evolution of copyright law. Even to this day, its impact is felt, however unrecognizable it may be. To understand all of this, it is best to turn the clock back by about a century.

American Backroom History

Early 20th century America saw moguls like William Randolph Hearst forging media empires, some of which have long endured. This was also an era when copyright and intellectual property laws in the United States were more limited in practice. As chaotic as it may have been—with states having their own conflicting (if not inconsistently enforced) policies—it nevertheless opened up new opportunities for creators pursuing newspaper strips, and what eventually became the first comic books. It was in this context that the first Tijuana bibles emerged in the 1920s.

It is unknown where these comics were first produced or even when. What is certain is that by the time the first arrests over such “obscene literature” were reported in June of 1926, they were already present in Midwestern towns in Indiana and Minnesota. Featuring then-popular characters such as Tillie the Toiler and the cast from the long-running strip Bringing up Father, these Tijuana bibles spread throughout the country over the next decade. It was not until the Great Depression, however, that they truly exploded in reach and infamy. According to cartoonist and Maus author Art Spiegelman, a total of about 700 to 1,000 distinct titles were estimated to have been made, with millions of copies produced and sold.

This feat could partly be attributed to the fact that anyone with a small printing press could mass-produce booklets with relative ease, though it is unclear whether such operations were purely “Mom and Pop” affairs or, more likely, were involved with organized crime. This was also helped by the fact that such bootlegging was done through varied distribution networks across state lines, from smuggling along railroads and discreet mail deliveries to simply stashing them in automobiles. Whether it was in one of the many sleazy shops in Times Square or outside schoolyards, once at their destination, these items were sold wherever there was a demand. And, in the 1930s, there was a lot of it to go around.

The sheer absurdity of seeing the likes of Blondie, Betty Boop, Clark Gable, and even Al Capone in pornographic misadventures often went hand-in-hand with the sort of irreverence that flew in the face of public morality.

Tijuana bibles, at this point, had diversified to include higher-quality “premium” versions that ran up to 16 pages. On top of parodying various fictional stars of their day, in a manner not unlike fanfiction, the subject matter came to encompass real-life personalities and original characters doing the deed. The sheer absurdity of seeing the likes of Blondie, Betty Boop, Clark Gable, and even Al Capone in pornographic misadventures often went hand-in-hand with the sort of irreverence that flew in the face of public morality. Yet, by the very same token, they provided much entertainment to many Americans, especially those suffering from the hardships of the Great Depression. Since these comics served as a discreet measure for the popularity of certain mainstream brands, many creators were content to let them be, with Li’l Abner author Al Capp going so far as to remark that he knew he had hit it big when Tijuana bibles began featuring his work.

Unfortunately, few names could really be ascribed to the authors behind the Tijuana bibles. While some booklets included a fictitious publishing company on the label, none had so much as a pseudonym for a by-line. As a result, collectors and aficionados over the generations came up with various monikers to identify these largely anonymous creators, such as “Blackjack.” One notable exception to this was freelance cartoonist Ainsworth “Doc” Rankin, who is believed to be the man behind “Mr. Prolific,” an artist responsible for 200 Tijuana bibles in 1930s New York, which often mirrored the source material almost uncannily. It is believed that at least some of these individuals may have also been industry professionals working incognito for extra cash or exposure, with Will Eisner reportedly turning such an offer down in what he would later recall as the toughest decision of his life. Without sufficient proof—and with the passage of time—the identity of the Tijuana bibles’ creators will likely remain unknown.

Perhaps this was for the best. Crackdowns on such material usually referred to as “obscene books” were not uncommon even at the heyday of bluesies—and would have ruined the artists’ careers if they were ever identified. Indeed, one of the more notorious cases on record happened during the 1939 World’s Fair, when the New York Police Department trailed peddlers to (and raided) a Brooklyn warehouse filled with over 350,000 booklets. Moreover, in addition to the kind of irreverence that some today would still consider “politically incorrect,” these booklets provided writers a means to express themselves without fear of censors or editorial oversight. Although such works were often not “political” in nature—usually translating to gratuitous cussing, crass stereotypes, and indulging in fetishes of all sorts—they also expressed political views that would not have been acceptable in polite society. Take, for instance, “That Nazi Man.” While it was very much a product of its times in treating homosexuality as “degenerate,” in its lampooning of Adolf Hitler, it also provided serious appeals against Nazism and anti-Semitism.

Beyond appealing to a distorted nostalgia for “the good old days” or shedding light on how the 20th century everyman entertained himself, to call Tijuana bibles a slap in the face to copyright law would be an understatement. Yet, they were also a vibrant expression of free speech, however crass or explicit they may have been. Given enough time and legitimacy, it is not hard to imagine how these comics could have fostered a creative media landscape that Americans today would find recognizable, if not iconoclastic. This was not to be, however. Circumstances conspired to snuff those flames out forever.

The End of an Era

Various explanations have been offered over the years as to what finally killed off Tijuana bibles. Rather than any singular cause, it is safe to say that a mix of factors was at play, with some being more significant than others.

The United States’ entry into World War II could arguably be seen as the beginning of the end. If the case of “Doc” Rankin’s later career is any indication, then it is also likely that many of the anonymous artists responsible for the booklets wound up being in the military, quietly “retiring” from their old habits in one way or another. This also translated into a decline in overall quality, as less competent artists tried to fill the void during and after the war, culminating by the late-1940s in the sloppy, mean-spirited diatribes of a man dubbed “Mr. Dyslexic” by Spiegelman. Meanwhile, wartime shortages in paper and other supplies resulted in production taking a significant nosedive. More frequent raids by law enforcement, especially by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, further crippled the old distribution networks and, as a result, dealt a hefty blow to the Tijuana bibles. A blow from which they would never recover.

Another reason was the emergence and popularity of glossy pulp publications after 1945. Whether it was humor-oriented Mad, “men’s magazines” like Man’s Life, or the likes of Playboy, these publications provided Tijuana bible authors a path towards legitimacy. More than just financial perks and a shot at being in the industry, these also gave such artists a degree of protection from the moral panic over comics that ensued by the early 1950s. Public backlash became significant enough, especially in the wake of Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, that there were fears within the wider industry of direct intervention by the United States government over “juvenile delinquency,” in which eight-pagers were particularly seen as indicative of that immorality. These sparked a chain of events that culminated in the establishment of the self-regulating and censorious Comics Code Authority in 1954.

Their fears about a chilling effect on free speech and creative liberties proved prescient in hindsight.

By the 1960s, what had been one of the most infamous pieces of Americana was reduced to obscure novelty items in adult stores, before quietly vanishing from view altogether. It was also during this time that trends in copyright law had begun coming home to roost. While many creators opted against prosecuting bluesie artists, it was an open secret that the Walt Disney Company was not at all happy with its intellectual property being violated or anyone challenging its image. In addition to redefining the public domain and maintaining its hold on Mickey Mouse indefinitely, the corporation’s lobbying efforts ensured that copyright infringements involving its brands would not happen again. This led to Congress passing the 1976 Copyright Act, which defined for the first time the factors for courts to consider in determining “fair use.” Tijuana bibles, by their very nature, would have been deemed a “market substitute,” lest artists risked being on the receiving end of hefty lawsuits from major corporations and publishers. Under such circumstances, sustaining a market—let alone continuing to produce booklets—was near impossible.

It was this ignoble turn of events that Krassner and Wood protested against with the “Disneyland Memorial Orgy” poster. Their fears about a chilling effect on free speech and creative liberties proved prescient in hindsight. Now, well into the 21st century, one need only look at those abusing YouTube’s Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown tools as a means of censorship and the mixed reception surrounding the CASE Act to see Krassner and Wood’s concerns largely vindicated. On a more mundane level, while the debate over fanfiction as legally acceptable has grown more positive (and the case for parody as being categorized under “fair use” or “transformative” has been successfully made in courts), the existing legal landscape all but ensures that creative work along the lines of eight-pagers will remain dead for the foreseeable future.

An Unlikely Legacy

Even as Tijuana bibles went into terminal decline, they helped to inspire comic book artists and cartoonists in later decades, from the early staff of Mad to Alan Moore. As Spiegelman and others have pointed out, they also ignited the rise of the underground “comix” industry during the 1960s and 1970s, which, in turn, gave rise to the “indie” comic scene during the 1980s. Although more politically charged—and not necessarily explicit—these comics nevertheless sought to retain the old irreverent spirit. The efforts made by collectors and artists to archive the booklets for posterity have similarly ensured that these comics will never fully disappear—no matter how much the Walt Disney Company or others want them to.

Coincidentally, one of Tijuana bibles’ most vibrant successors can be found across the Pacific. Japanese self-published works—or doujinshi—have emerged independently over the past 100 years. Despite the country’s common perception as being culturally conservative, the growth and evolution of this scene mirror the rise of Tijuana bibles, which also use existing characters. If anything, some of the material sold in events such as Comiket can be even more overt, transgressive, and graphic than yesteryear’s bluesies. Unlike their predecessors, not only have advances in photocopying (and later access to the Internet) given “doujin” creators greater control and reach than their American counterparts but the tacit permission of intellectual property holders and publishers in general—despite technically falling foul of Japan’s copyright law—has fostered a sizable industry like no other, with some creators having even become distinguished professionals in their own right. It is difficult to say, though, if this can last indefinitely.

For that matter, the future of free speech and copyright law remains murkier than ever, and much could happen in any direction. Nevertheless, the legacy of the eight-pagers and their impact on the wider cultural milieu cannot be erased as easily as some might have hoped.

Carlos Miguel del Callar is a freelance writer in the Philippines.