“Patience ‘is the central constitutional virtue—and it is, by all signs, a lost one.'”

To understand our political malaise, we should approach it from multiple analytical angles. We can divide the most common of these approaches into two groups, broadly speaking: (1) those that frame our political troubles as downstream from our societal ones and (2) those that see our political discord and dysfunction as stemming from the artificial separation of American politics from our wider society. Both frames help us inch closer to a more comprehensive understanding of why American politics is so, well, terrible.

Political Defects as Downstream from Societal Defects?

The first approach emphasizes the role of our social disorders and divides in creating our unhappy politics. This line of argument sees our partisan sorting into geographic enclaves and media silos as a key driver of our political discord. Even as American society grows increasingly diverse on the whole, that diversity is not spreading itself out over the wider country in an even manner. Despite our immense racial diversity, we are still an exceptionally segregated country (including within our most racially diverse places—our cities). In education, school segregation arguably has been on the rise in recent years. And our social separation does not only run along the lines of race. As consumers, we enter into a market that is tailored to our most hyper-specific needs and desires, and we are increasingly sorting into one of the two parties on the basis of our places of residence and consumerist tastes. Under this view, our divided politics is not that unique from our divided and separated society.

Also falling under this umbrella—the view that our political troubles stem from our wider societal troubles—is the argument that a democratic-republican political culture of responsible self-governance cannot magically arise from a society where the virtue of self-control is somewhat lacking. It is not a secret that our contemporary culture places a premium on self-expression and authenticity. Those who are true to themselves—and the urges, interests, and passions that comprise the self—are lauded. Compared to the past, today we place far less emphasis on being shaped by the wider society and its core institutions like organized religion, the family, and school. Under this view, our performative Congress is not a far cry from our performative society: lots of people “being themselves,” while neglecting the constraints and norms that make Congress a lawmaking body and not just another shouting Sunday show.

Political Defects as Artificial Creations of Poorly Designed Institutions?

The second group of approaches to American political dysfunction views that dysfunction less as an organic consequence of social realities and more as the artificial upshot of highly flawed institutional arrangements unique to politics. The unfairness of gerrymandering, the undemocratic Electoral College, the distorting effects of partisan primaries, and overly lax campaign finance regulations are some of the key institutions and policies towards which this group directs its ire. These institutional structures, they argue, distort our politics. They cater to well-funded extremists and niche causes that, in fact, run counter to the preferences of a quiet, centrist, reasonable majority that spans both the Democratic and Republican parties. A generally centrist nation, so the argument goes, is increasingly forced to choose between two political extremes.

When Institutional Norms and Societal Norms Don’t Mix: Disillusionment?

Both of these approaches have significant explanatory value. There is an oft-neglected third approach, though, that complements these first two: the immense amount of friction and disillusionment that is caused by the incompatibility of our political institutions and some of our social impulses and norms.

Take the example of instant gratification. We now have the tools to instantly gratify ourselves in a variety of ways, if we so choose. Just about any type of food is a single Uber Eats order away. If we want to express rage or frustration and let everyone know about that rage or frustration, Twitter is right at our fingertips. Likewise, sexual self-satisfaction is just one pornographic web click away. Food, emotional outbursts, sex—we can satisfy many of our most base urges with a click of a button.

This slow tempo of action and progress is alien to us in the context of our personal and social lives here in the 21st century, but, in our political lives, we are forced to deal with it.

But our plodding, exceptionally brilliant constitutional system is a major exception to this contemporary social trend of the quick hit. Constitutional features like checks and balances, the separation of powers, and federalism converge to produce a constitutional system that makes political success a painstaking, slow, and arduous process. This slow tempo of action and progress is alien to us in the context of our personal and social lives here in the 21st century, but, in our political lives, we are forced to deal with it. This often results in political disillusionment and alienation from our political institutions: We cannot bring ourselves to say that the system is simply slow. No—it must be “broken” or “rigged.” We cannot fathom that there are stubborn roadblocks standing in the way of our will, given that the mix of contemporary culture and technology have all but removed many will-constraining roadblocks in the realms of the personal and the social.

When we understand precisely why our constitutional system was designed to be so slow and, at times, frustrating, we might come to appreciate it a bit more. Understanding and knowledge can help chip away at anti-institutional and anti-constitutional disillusionment and grievance.

That said, when we gain a stronger grasp on the slow-moving design of our constitutional system and the reasons for it, we might also discover justification for certain political reforms: Some of our political norms and practices today not only slow the pace of our politics and the will of majorities but consistently thwart majorities. As such, those norms and practices might be woefully out of step with the original rationale for America’s pace-slowing constitutional system.

Slowness as a Feature, Not a Bug

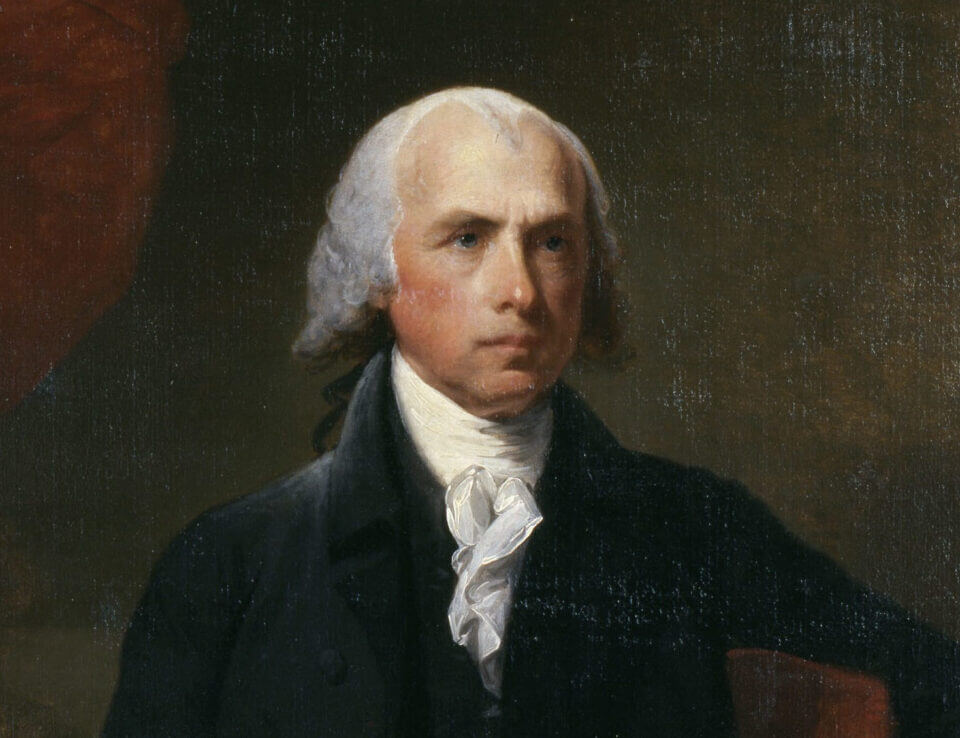

In his 2012 book Madison’s Metronome: The Constitution, Majority Rule, and the Tempo of American Politics, Assumption University professor and American Enterprise Institute visiting scholar Greg Weiner explains that the slow-moving nature of American policymaking is very much a feature of our constitutional system, not a bug. Probing the “temporal republicanism” of James Madison, Weiner argues that Madison was a veritable democratic-republican through and through: He saw majority rule as both normatively preferable and empirically inevitable. That said, Madison was under no illusions regarding the potential pitfalls of majority rule. Weiner persuasively makes the case that Madison framed a number of the key elements of his constitutional thinking as means not to thwart the rule of the majority but, rather, to slow it down. For Madison, writes Weiner, “Because time defuses the passions, majorities should prevail only after cohering for an interval sufficient to ensure that reason rather than impulse guides their will.” Constitutionalism itself is a means of slowing down and tempering the whims of the majority; under a system of government premised on popular sovereignty like ours, constitutionalism is a restraint that the people willfully place upon themselves. Madison went further still in advocating certain constitutional mechanisms that were specifically geared towards slowing down, albeit not thwarting, the wills of majorities.

For example, Weiner makes a persuasive case that along with the separation of powers and even the Bill of Rights, Madison’s theory of the extended republic that he famously expounded in Federalist No. 10 serves the cause of temporal republicanism: “An extended republic naturally filters out proposals based on [the] forces [of passion and temptation] because the time required for a majority to coalesce and prevail across broad expanses of territory exceeds the lifespan of a typical eruption of passion.” Weiner goes too far in saying that, for Madison, “The relevance of the country’s large geography was the time required to traverse it.” His exceptional analysis makes clear that this is an overlooked part of Madison’s thinking. That said, a plain reading of Federalist No. 10 suggests that the core rationale for “extending the sphere” is still taking in numerous factions. With multitudinous factions jockeying for power, a single faction is less apt to predominate in the extended republic than it is in a small republic. The basic understanding of the tenth Federalist still holds, though Weiner’s time-centered gloss on it is important.

In Madison’s mind, passions and quick thinking went together, as did reason and slow deliberation. Indeed: “The concepts of the immediate and the ultimate operate in Madison’s thought as almost exact parallels to passion and reason.” Thus, the longer it took for the majority to enact its will into law, the more time there would be to ensure that reasonable provisions—those that respected minority rights and actually advanced the common good—would prevail, while support for unreasonable, passionate initiatives would wither away. Weiner writes: “Madison believed majorities or their leaders should prevail when cold, considerate, and cautious; those heated by passion should be stalled.” Forcing them to cohere for a sustained period of time would serve this end in Madison’s mind, since he viewed passionate majorities as “inherently fleeting” and “not persistent.”

The Virtue of Patience

The final chapter of Madison’s Metronome is fascinating, as Weiner notes that in the 18th and 19th centuries when Madison was pondering how best to temper, rationalize, and soothe majorities, the technological constraints of Madison’s day naturally provided his preferred balm of time. Prior to our immense improvements in communications and transportations technologies, it would inevitably take a good bit of time before a majority could grow aware of itself, gather, and push its will through the political channels. Without technological limitations imposing this temporal constraint, writes Weiner, “a virtue must intervene: patience.” Patience “is the central constitutional virtue—and it is, by all signs, a lost one.”

And so Weiner has ushered us back to the conundrum outlined above: We live in a society that places a premium on instantaneity and under a Constitution that, deprived of the pace-slowing limitations of technology, increasingly calls on us to exercise the virtue of patience. This is one of the central constitutional challenges of our time, and the past few decades have indicated that we are far from capable, as things currently stand, of meeting it. The turn to the courts to settle political disputes, which Weiner laments in Madison’s Metronome and elsewhere, indicates that we are not willing to subject ourselves to the slow-moving pace of American politics. The courts present a welcome political version of the quick hit, the instant result. While Weiner is correct to lament this litigatory turn in our politics, his study of Madison’s temporal republicanism also might indicate that some of the majority-thwarting structures of modern American politics might need to be peeled back. If we are to rediscover republican self-government—if we are to have faith that our political channels, instead of the courts, can be responsive and deliver real policy wins—we might need to remind ourselves that Madison sought to temper majorities, not thwart them.

The Case of the Filibuster

Take the example of the much-derided Senate filibuster. I am not here to weigh in definitively on the fraught controversy over the filibuster. But having read Madison’s Metronome, it seems fair to question whether super majoritarian mechanisms like the filibuster, which was not a part of the framers’ original design for the Senate by any means, are worth keeping. Patience ought to have its limits. Our political landscape must make sufficient room for majorities to feel agency, to have a sense that they do, indeed, have the power to enact much of their will into law. Super majoritarian requirements like the one enshrined in the Senate rules by the filibuster seem to result in three things: fewer policy wins in Congress (and, thus, greater willingness on the part of the public to turn to the courts instead), more unwieldy and sloppy simple majoritarian mechanisms to work around the filibuster, and the most meaningful legislation working itself through Congress only in the event of a crisis. This is not optimal, nor does it stay true to Madison’s understanding of temporal republicanism: Remember, the goal is not to thwart a majority—the goal is to slow it down.

A democratic-republican through and through, Madison saw majority rule as both a normative good and an empirical fact.

Perhaps rather than elimination, filibuster reform—such as limiting the frequency of its usage as Benjamin Pontz and Gettysburg College Professor Scott Boddery recently proposed in The Dispatch—is the way forward. At any rate, mechanisms like the separation of powers and legislative bicameralism already slow the governing pace of majorities in America to a considerable extent. A 60-vote requirement in the Senate may be doing more harm than good.

Putting the specific issue of the filibuster aside, engaging with Madison’s political thought should leave us both with a renewed focus on cultivating civic virtues like patience and a recognition that such virtues have their limits. A democratic-republican through and through, Madison saw majority rule as both a normative good and an empirical fact. The question that permeated his political thought was how to harmonize majority rule and the public good. Tempering, not thwarting, was his method. We would do well to follow in his footsteps as we seek to cultivate social norms and virtues more becoming of a republican people, while also ensuring that our political institutions are sufficiently responsive to ward off further disillusionment.

Thomas Koenig is a recent graduate of Princeton University and will be attending Harvard Law School in the fall of 2021. He can be found on Twitter @TomsTakes98