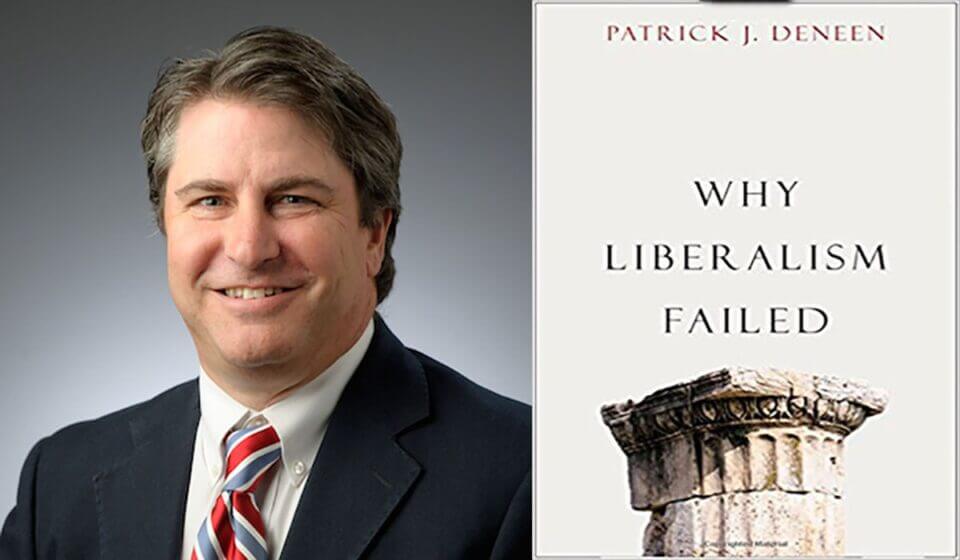

“This conquest of the engines of social formation is, as Patrick Deneen argues, why liberalism is failing.”

The fundamental questions of human life are no longer answered. And the asking of them brings derision or a lack of recognition, engendered by living in a system of thought for so long that it acts as the water in which we swim. Our origins, purpose, and existential goals are supposedly no longer important. Liberalism has occupied the commanding heights of political philosophy, and—when instantiated as the hegemonic ideology of societal institutions—it becomes the ideology to which there is no alternative. This conquest of the engines of social formation is, as Patrick Deneen argues, why liberalism is failing. Its increasing success has led to increasing failure. We are all now living with the consequences of this conquest.

Liberalism and its Discontents

We all know something is deeply and fundamentally wrong. Society, if it even exists, has gone in the wrong direction. We are unhappier than we have been for decades. We are lonelier, less connected, and are less able to find the meaning in relationships that is essential for living a good life.

Patrick Deneen writes in Why Liberalism Failed that “Liberalism has failed–not because it fell short, but because it was true to itself. It failed because it has succeeded.” In becoming more of itself—and being implemented by those in power more in concert with its fundamental principles—it has revealed its inherent internal contradictions to a greater and greater extent. Liberalism, a political philosophy launched to “foster greater equity, defend a pluralist tapestry of different cultures and beliefs, protect human dignity, and, of course, expand liberty, in practice generates titanic inequality, enforces uniformity and homogeneity, fosters material and spiritual degradation, and undermines freedom.”

What is liberalism? For Deneen, writing in an American context, liberalism is not the purview of one side of the political spectrum but, rather, the foundational reality that underpins both sides of the Anglo-sphere’s political spectrum. This foundational reality has its origins in the work of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Hobbes recast human political relations as fundamentally individualistic, albeit with an overbearing strong government to guarantee one’s personal safety. John Locke built on this in his Second Treatise, casting individuals as rational and equal autonomous units, without the imprint of cultural or political particularity, born out of place and time, with no memory of the past or conception of the future. These autonomous individuals come together in the pre-civilizational state of nature to form a community and a government through the social contract, created through the consent of all involved and dissolvable at any time. In the liberal origin story, government is created by the individual to further his liberty and freedom and to fulfill individual desires according to his will. The state is created by—and creates—the individual. This fictitious origin is so fantastical that Roger Scruton argued that Marxism was a more realistic and believable philosophical tradition than liberalism because “it derives from a theory of human nature that one might actually believe.”

Liberalism was not—and is—not concerned with the common good but with a modus vivendi between disparate groups espousing incommensurable values. The maximization of liberty through this was the highest good of liberalism. All the institutions that formed and shaped the human individual to become a responsible, self-governing member of the community were written out of liberalism at its foundations. Man was left alone, unattached and isolated. Deneen calls this “Anticulture.” Deneen defines culture as practices and institutions that almost always embody and cultivate a belief in the link between human nature and the natural world, the penetration of the past into the present, and the present into the future, as well as attachment to one’s place, imbued with sacred gratitude.

Liberal anticulture rejects all of these, since they all place limits on one’s ability to be an entirely self-making author of one’s own autonomous destiny. Anticulture, Deneen argues, rests on three pillars: “first, the wholesale conquest of nature…second, a new experience of time as a pastless present in which the future is a foreign land; and third, an order that renders place fungible and bereft of definitional meaning. These three cornerstones of human experience–nature, time and place –form the basis of culture, and liberalism’s success is premised upon their uprooting and replacement with facsimiles that bear the same name.”

A core feature of liberalism is a deep hostility to culture as something that defines and places limits on human nature. The placelessness of the state of nature is integral to liberalism, which emphasizes liberation from continuous time as liberation from our basic nature. The institutions, structures, and practices that shape our self-governing mastery over inner desire must be disassembled, setting us loose in a nowhere of time, free from memory of the past and obligation to the future. Deneen cites Alexis de Tocqueville to argue that timeless presentism enabled the dissolution of formative practices and structures to separate people’s capacity to discern a shared fate. This would lead to a new, self-congratulatory aristocracy of the successful. The geographical separation of the meritocratic Overclass from the populace shows the prescience and accuracy of this claim. The fracturing of time is embraced and entrenched by this class as a form of freedom, a dissolution of personal obligation to a shared past, future, and present.

In Deneen’s view, the modern left and right are, thus, simply variations in liberalism, not differences in kind.

When manifested in real life, anticulture has caused social problems that our compromised institutions today cannot conceive or address, let alone mend. The erosion of embedded culture enables the liberation of the placeless and timeless individual into the pervasive, all-encompassing market, alongside the empowerment of the state. A liberal individual, writes Deneen, “demands the dismantling of culture; and as culture fades, Leviathan waxes and responsible liberty recedes.” Freedom as license leads to constant expansion of arbitrary state power to pick up the pieces of the collateral damage resulting from the untutored exercise of arbitrary personal freedom.

In Deneen’s view, the modern left and right are, thus, simply variations in liberalism, not differences in kind. While this may, indeed, have been the case in America since its inception, it became increasingly the case in Britain from the end of the 19th century and then really came into its own under Margaret Thatcher and her heirs John Major, Tony Blair, and David Cameron. Both sides promise and exist to spread freedom and individual emancipation to more and more people, in more and more areas of life, through the transformation of more and more institutions.

The modern left has invested in expanding social liberation, encouraging the growth of socially acceptable lifestyles, while withholding judgments on the outcomes of these choices. Meanwhile, those who hold to older forms of social forms are castigated as inherently bigoted and prejudiced—again liberalism’s neutrality for the lie it is. Cultural relativism for me, but cultural absolutism for thee. The modern right, meanwhile, is invested in enabling and expanding personal liberty through the depersonalized space of the market, with the constant expansion of self-actualization through economic actualization. The pursuit of “rational self-interest” is the highest good of modern so-called conservatism.

Never mind the reality of the “invisible hand” being a visible fist in a velvet glove that picks winners and losers under the guise of meritocracy, shouting down those like Joel Kotkin impertinent enough to raise the issues of spiraling income inequality, the increasing proletarianization of the middle class, and the growing reality of a serf class serving an insulated oligarchy or overclass legitimized by an obsequious clerisy in the elite cultural institutions in the arts, media, law, and academia.

Both sides of our modern political spectrum service an ideology that neither can see any alternative to. Liberalism was “the first of the modern world’s three great competitor political ideologies, and with the demise of fascism and communism, is the only ideology still with a claim to viability. As ideology, liberalism was the first political architecture that proposed transforming all aspects of human life to conform to a preconceived political plan.” The penetration of liberalism into every corner of our political and cultural life has happened slowly and without much notice, with its offers of ever-increasing freedom and autonomy an evergreen source of attraction for successive generations.

However, as it has gained control of the political and cultural structures in our societies, the emancipation that liberalism has offered, the dissolution of barriers to our freedom have instead hardened into new barriers. As Deneen writes, ideology in politics always fails, “first, because it is based on falsehood about human nature, and hence it can’t help but fail; and second, because as these falsehoods become more evident, the gap grows between what the ideology claims and the lived experience of human beings under its domain until the regime loses legitimacy.” To shore up their dwindling legitimacy, ideologies enforce conformity to their indefensible tenets, or collapse comes when the gap between the claimed reality of its adherents and the perceived reality of the populace becomes too great to ignore and the whole thing falls apart.

For Deneen, “humanity comprehensively shaped by liberalism is today burdened by the miseries of its successes. It pervasively finds itself to be caught in a trap of its own making, entangled in the very apparatus that was supposed to grant pure and unmitigated freedom.” This disjunction between promise and reality is felt and seen in the realms of politics and government, economics, education, and science and technology. The institutions of each have been transformed continually to push the liberal highest good of ever-increasing freedom and control of our destiny. Instead, as Deneen writes, “widespread anger and deepening discontent have arisen from the spreading realisation that the vehicles of our liberation have become iron cages of our captivity.”

In politics, liberalism was “premised upon the limitation of government and the liberation of the individual from arbitrary political control.” And yet, government today in our Anglo countries is a massive, intrusive force that simply varies in its state capacity, its proficiency at interfering and ordering our lives in a consistent and predictable way. The liberties of thought, speech, association, and governance that liberalism promised are compromised beyond recognition. This is not a defect, not an aberration in liberal political society. The erosion of civil society in favor of increasing individual autonomy (and the resultant loss of support rooted in solidarity) leads to calls for the state to fills the gaps left behind, which, in turn, worsens the problem.

The unease and discontent manifesting in our political spheres is mirrored in the economic realm. We are still constantly told—in voices of increasing shrillness—that true economic freedom is that which allows us to buy more and more for less and less, while simultaneously freeing us from the bonds of family, community, and nation, divorced from memory, time, or place. Everything must serve the market, the economic engine for increasing individual freedom. The invisible hand requires the visible state apparatus to create the deracinated, deterritorialized conditions necessary for the market to undo the ties of tradition and particular culture.

As Deneen argues, none of this assuages the increasing precarity so many in the younger generations experiences, nor does it salve the scars on our souls that late modernity leaves. The brutal Darwinism of modern markets—again in hoc to supposed meritocracy—leaves more and more aware of the generational conditions for winning and losing. Economic inequality has always existed and will continue to do so. Attempts at equality of condition leave only equal access to rubble. The inequality we currently see is something different in kind and leaves one in a mindset of serfdom, not freedom. The alienation from labor that Marx described was also discussed by Roger Scruton, who argued that conservatives should recognize this spiritual malaise in deficient modernity, seeking to “present his own description of alienation, and to try to rebut the charge that private property is its cause,” while recognizing “that civil order reflects not the desires of man, but the self of man.”

Economic alienation is joined by the aforementioned geographical alienation enabled by a fractured sense of time divorced from place and community. The globalized economy and its elite overclass physically and psychologically removed from everyone else, pacified with somatic consumer sedatives. Even so, protests against this supposedly “inevitable process” repudiate the standardization and homogenization that this process brings about. According to neoliberal left and right, economic globalization is a “process and logic [that] can no longer be controlled by people purportedly enjoying the greatest freedom in history.” In reality, “the wages of freedom are bondage to economic inevitability.”

The logic of the market, of inevitability twinned with and growing out of man as economic material, what Heidegger called a “standing reserve,” has infiltrated and poisoned the world of education. Using language reminiscent of Irving Babbitt’s New Humanism in which he described man comprised of a lower, base nature and a higher, enlightened nature, Deneen argues that education was—and should be—for the cultivation of one’s higher nature through shaping one’s soul to the good. Great texts in the liberal arts “were great not only or even because they were old but because they contained hard-won lessons on how humans learn to be free, especially free from their insatiable desires.”

This is freedom as self-mastery through learning, not freedom to do as one wills. Now, we hear constant calls for practical education in utilitarian technical subjects, subjects where we learn “how,” not “what,” “when,” or let alone “why.” Today, Deneen writes, “liberals condemn a regime that once separated freeman from serf, master from slave, citizen from servant, but even as we have ascended to the summit of moral superiority over our benighted forebears by proclaiming everyone free, we have almost exclusively adopted the educational form that was reserved for those who were deprived of freedom.” Educational establishments, once institutions for the cultivation of virtue, historical awareness, prudence, and an obligation to the future are now the prime producers of individuals steeped in liberal anticulture. In education, anticulture erodes and erases knowledge of particular ways and means of cultures and traditions rooted in particular times and places. Instead, the free individual is primary, taught how to exercise his untrammeled will in the sexual and economic marketplace. All this in service to an economy that decides the price of the heart through addictive hedonic capitalism but ignores—and, indeed, actively denigrates—the value of the soul.

Science and technology are the means of pushing this project of enslavement-as-liberation forward. Modern science is portrayed as a means of liberating ourselves from the limits of nature itself and for controlling and dominating the unpredictability of our natural order. We are Francis Bacon’s children, Deneen avers, always attempting to wring the secrets out of the nature we seek to imprison and control. The environmental degradation and damage we see all around us are irrefutable evidence of the battles for control being lost in a war for dominance we cannot win, no matter our delusions of hubristic grandeur. In Deneen’s words, “We still hold the incoherent view that science can liberate us from limits while solving the attendant consequences of that project.”

Meanwhile, our technology is succeeding as almost nothing else has in separating us into the individual atoms that were our supposed origins in the state of nature fantasy land. Place, time, community, and identity are irrelevant in the grey environs of what Mark Dooley calls Cyberia. The devices that proclaim are liberation instead imbue our homogenization and conformation. In looking for togetherness to ease our loneliness, we instead grow further apart, ending up alone together, as Sherry Turkle puts it. The ultimate symbol of this is the drive to remake humanity itself, transcending our mortal frames through cybernetics of uploading to the cloud, forever returning through an eternal “refresh” function.

Leaving Odysseus Behind

Ultimately, as Deneen argues, from its origins at modernity’s beginning in the 17th century, liberalism “is shaping us into the creatures of its prehistorical fantasy, which in fact require the combined massive apparatus of the modern state, economy, education system, and science and technology to make us into: increasingly separate, autonomous, nonrelational selves replete with rights and defined by our liberty, but insecure, powerless, afraid and alone.” Liberalism, by endowing us with infinite choice, renders us unable to make any of the meaningful choices that Odysseus made in the Odyssey, as we saw last time. The choice to accept the limits of mortality, place, and polis (community) is stripped away from us by the overbearing administrative state and the encroachment of the market. Instead, “our liberation render us incapable of resisting these defining forces—the promise of freedom results in thralldom to inevitabilities to which we have no choice but to submit.” Odysseus’s conflict of the soul was whether to accept the givenness of his condition, or to accept the gift of transcendence offered by Calypso. The opportunity for seeing outside the Platonic cave of existence was there before him, but Odysseus chose to remain in the cave, having glimpsed what lay outside it.

Instead of a grounding in time, place, and community, liberalism instead encourages us to take the wandering path that Odysseus might have pursued for the rest of his everlasting days if he had accepted Calypso’s offer.

This is what liberalism destroys. It both offers the chance to leave the cave of the gift of our existence, and then prevents us from either remaining or reentering. This choice, in an ideology built on choice, is the one illegitimate decision that we cannot make, lest we disrupt the progress towards the liberal highest good of ever greater autonomy and choice through unfettered will. Instead of a grounding in time, place, and community, liberalism instead encourages us to take the wandering path that Odysseus might have pursued for the rest of his everlasting days if he had accepted Calypso’s offer.

The depersonalization and abstraction on offer are a thin substitute for the consolations of meaningful relationships, worship, and work that might otherwise be possible. Our main political choices, as Deneen says, “come down to which depersonalised mechanism will purportedly advance our freedom and security—the space of the market, which collects our billions upon billions of choices to provide for our wants and needs without demanding from us any specific thought or intention about the wants and needs of others; or the liberal state, which establishes depersonalised procedures and mechanisms for the wants and needs of others that remain insufficiently addressed by the market.”

The opposition of the state and market, and what this means for individual liberty, that still forms the core of our politics of the spectacle is in reality a false one. They grow together and cannot do otherwise. When man is reduced to his own resources, without recourse to family, community, locality or civil society, the state that has an interest in enabling this state of affairs inevitably grows into the void left behind. This is perhaps one of the key points of Why Liberalism Failed: “Statism enables individualism, individualism demands statism.” Thus, “modern liberalism proceeds by making us more individualist and more statist.” Both sides “move simultaneously in tune with our deepest philosophic premises,” perpetuating a spiral that promises greater and greater freedom and liberty, but which in reality sends us sliding down a slope towards greater and greater despair and anomie. It turns out that despite all the emphasis on infinite choice, what liberalism cannot do is allow us, in the words of Deuteronomy 30:19, to “therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live.”

Where Next?

Many have criticized Deneen for the paucity of the solution he provides to the terminal diagnosis he renders. Fine, they say, these are the problems, but what is the solution? Before he can even begin, however, Deneen is often accused of wanting to turn the clock back, throw women back in the kitchen barefoot, lock gay people back in the closet, and reintroduce segregation. This is frankly stupidity leveled by people too lazy to read the book and too uneducated—despite their impressive credentials—to understand it even if they did. As Deneen rightly says, there is no going back. The past is in the past, beyond the veil of time behind which we cannot reach or see clearly. What happens next is in our hands.

Leaving liberalism behind, as many in the admittedly still fuzzy post-liberal world of thought wish to do, does not mean jettisoning the benefits that were attendant to it. Deneen is correct when he says that “moving beyond liberalism is not to discard some of liberalism’s main commitments–especially those deepest longings of the West, political liberty and human dignity—but to reject the false turn it made in its imposition of an ideological remaking of the world in the image of a false anthropology.” In other words, to paraphrase the great philosopher and Renaissance man, Ozzy Osbourne in the Black Sabbath song “Supernaut,” post-liberals have seen the future under liberalism, and we have left it behind.

It is crucial that post-liberals define what it is that comes next. It is of no use simply to define and delineate liberalism’s fatalities. To rebuild we need something that can enable a rebirth, that allows for the flourishing of the fully human person. In my less than philosophically trained view, the fundamental tenet of post-liberalism is that man is a relational being, bound by limits of time and place, and he reaches the universal truths (on which we base our social and cultural realities) through the particularity of experience, community, and tradition.

We must repudiate the weightless universalism of both right and left-wing neoliberalism, as well as the crushing weight of exclusivist particularism of the new and dangerous movements towards absolutist identity politics of immutable characteristics, both in its left-wing Critical Theory and its right-wing identitarian modes. For Scruton, however, liberal anthropology “isolates man from history, from culture, from all those unchosen aspects of himself which are in fact the preconditions of his subsequent autonomy.” This existential loneliness leaves young people, in particular, desperately seeking for ties to bind themselves to others with which to face the vicissitudes of life.

In my own life, neither liberalism nor its identity-politics alternatives are sufficient to meet the needs of a life well-lived. The belief and genesis story of liberalism is shown up to be the fantasy that it is by life itself. Having a disability—as I do—emphasizes its malign falsity. Under liberalism, those like myself should be left to rely on our own resources of autonomy, undeniably limited by physical reality though they may be. In reality, liberation from the support of others is revealed as cruelty under the guise of compassion. Man’s fundamental interdependence and reliance on others is revealed day after day in my life. This is a thorough repudiation of liberalism’s central claims.

The rising identity politics of left and right poses a further threat. The left identitarians wish to imprison me in the chains of my disability, reifying this politicized identity to define me solely by this one characteristic. The right identitarians, meanwhile, mirror this view but instead wish to purge those pollutants like me from the racial bloodstream. None of the above provide the means for people like me to live a fulfilled, meaningful life.

The mediation of the universal by the particular discussed in part one of this series was brought home to me by the work of Roger Scruton. His writing on philosophy, politics, religion, and the sacred left me with a sense of connection to the past, the present, and a sense of purpose derived from responsibility for the future. We are all, as Heidegger wrote, thrown into this world. We must all deal with the alienation and isolation attendant to our fallen humanity.

Liberalism, through its entrenchment of isolation and loneliness as autonomy, and its constant deconstruction and repudiation of the familial, communal and national bonds that are a blessing rather than a burden, actively suppresses this search and attainment of relationality across time and love for people and place in the here and now. Having a disability means that the struggles common to all in this regard are heightened considerably, sometimes unbearably. The solitude of being shut up in one’s own heart, as de Tocqueville put it, is often the reality. The work of Scruton enabled me to feel at home in the world, with a greater sense of embeddedness in time and place. The liberalism that Deneen describes and criticizes denies this source of consolation that makes life worth living. The work of both has provided solace and guidance in a fast-changing, confusing world. Life’s journey is long, as Odysseus discovered, and if we are lucky enough to find those who can help us find a way to a sense of home in our time here on this earth, we should be thankful.

Both pathologies of weightless liberal universalism and exclusive identitarian particularism are inimical to the good life. They must be resisted by those who wish to both move on from the failures of liberalism and prevent these dangerous movements from dragging us over the edge into conflict, unrest, and ceaseless tribal violence. Ultimately, both Deneen and Scruton—in their embrace of the limits of time, place, and community and the hope they paradoxically provide—rest their work on a foundation of gratitude for life itself. This is where post-liberalism should begin.

Henry George is a freelance writer from the U.K., focusing on politics, political philosophy, and culture. He has also written at Quillette, Arc Digital, Reaction, The University Bookman, and Intercollegiate Review.