“…nor could [Houellebecq] have emerged from the hundreds of wallet-siphoning creative writing MFA programs, whose grasp on the American literary world has sanitized literature to an unreadable degree.”

There is a scene that comes late in Michel Houellebecq’s new novel, Serotonin, where the protagonist Florent-Claude (a name he hates) goes to rent a house in the French commune Saint-Aubert-sur-Orne from a middle-aged, divorced, self-described “failed” architect, whose life he sees as so similar to his own that it is, “almost becoming oppressive.”

Whether their lives are really that similar or whether Florent-Claude is merely projecting his own failures onto this man’s life is a matter of interpretation. But when his future landlord warns him there isn’t any Internet connection in the house and Florent-Claude doesn’t seem to mind, he worries the landlord might think it strange because, “people who agree to cut themselves off from the Internet for an indefinite period without even wincing are up to no good.”

In fact, Florent-Claude is up to no good. He’s looking for a house to stalk (and perhaps something worse) an ex-girlfriend, Camille, whom he regrets ruining his relationship with years ago, for one lusty unfaithful night with another woman.

“‘I’m not going to kill myself,” he reassures the landlord, “…Well, not right now.’”

Later, after he moves in, Florent-Claude is surprised to discover the complete works of the Marquis de Sade on the architect’s bookshelf; and on the abandoned mezzanine with “disemboweled sofas with moldy fabric, half-upside down on the floor,” he finds a record player with a dusty collection of 45s, mostly “twist records:”

“In fact he must have had a past in the house, a past whose outlines I struggled to, define—somewhere between the Marquis de Sade and the twist—a past that he needed to get rid of, even though that wouldn’t open up the possibility of the future…”

Of course, it is Florent-Claude who has a past he needs to get rid of. He is “dying of sorrow” as his doctor tells him. The anti-depressants he’s used to damper his despair have now become a danger to him and threaten his health. Unfortunately for Florent-Claude, he’s in a Michel Houellebecq novel, which is a place of despair, alienation, loneliness, and not much hope.

He understands that provocation is a necessity to disrupt and explode taboos, which may be the only way to get beneath the surface of a surface-level society.

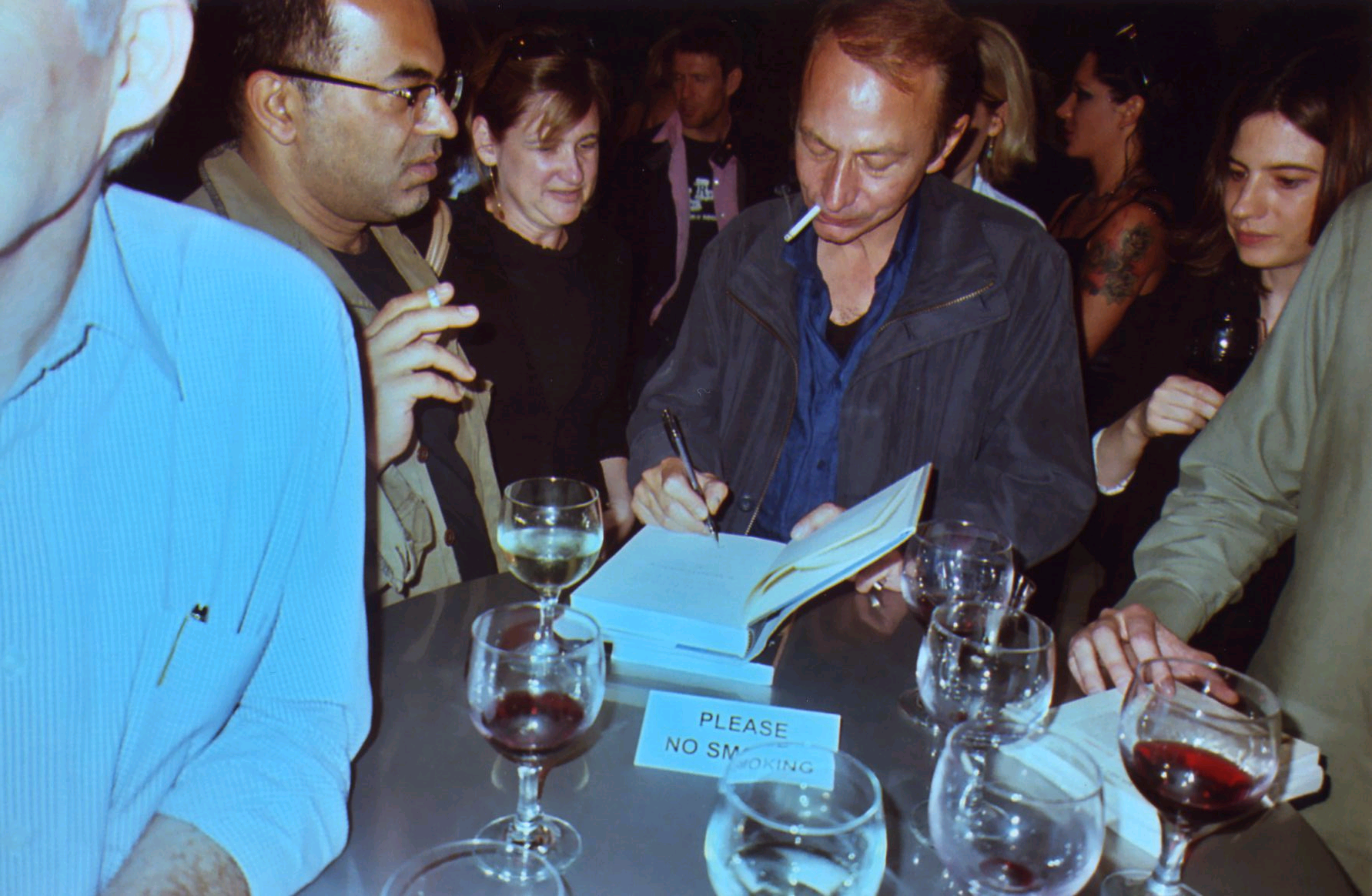

Reading Houellebecq in 2019, twenty years after I first did, feels more provocative than ever. It’s not that he’s changed—the culture has. This is a frigid age. After all, we live in an era in which a Batman movie causes moral panic. If Houellebecq were a first-time American novelist trying to get published in the United States today, it would never happen—nor could he have emerged from the hundreds of wallet-siphoning creative writing MFA programs, whose grasp on the American literary world has sanitized literature to an unreadable degree. Luckily for us, Houellebecq is neither American nor a first-time novelist. Nor is he an academic. If anything, he’s a punk—who learned how to write not in some university workshop, but in a “tiny room, bare save for a mattress, some alcohol, and a huge poster of Iggy Pop on the wall,” as Geoffrey Macnab writes in The Independent. (Years later, Houellebecq would return the inspiration, when Pop modeled his album Préliminaires off the author’s 2005 novel The Possibility of an Island.)

Like punk, Houellebecq’s voice and style is authentic and raw, and in its response to the conditions of modern life, makes use of self-reflexive irony (especially in his novel The Map and the Territory), and the need to shock. He understands that provocation is a necessity to disrupt and explode taboos, which may be the only way to get beneath the surface of a surface-level society.

Overall, Serotonin is not his strongest work to date, but its rare honesty functions like a chemical spike in a depressingly gray literary world. For any longtime fan, it may feel a bit like a pastiche of all his previous work, even parody, particularly in the sad man narrative and in the revisiting once again of his favorite theme, the decline of the West, whose citizens are bereft of any meaningful experience and resolved to a life of pill-popping, sex-obsession, and suicide contemplation. (It’s no surprise that Houellebecq won the first ever Oswald Spengler award by the Oswald Spengler Society last year.)

Stylistically, one could argue, as Houellebecq’s content grows rawer (and possibly more sadistic towards his characters), his sentences grow more elegant, with more twists and turns, but always with clarity.

If he has a target to attack in this novel, it is perhaps hypocritical progressive elites, the cultural authority of the day. And as bleak as the book can get, it also twists into hilarity in places. (Something people often miss about Houellebecq—how darkly funny he can be):

“I hated Paris, that city infested with eco-friendly bourgeois repelled me. Perhaps I was a bourgeois too but I wasn’t eco-friendly; I drove a diesel 4×4—I mightn’t have done much good in my life, but at least I contributed to the destruction of the planet—and I systematically sabotaged the selective recycling system put in place by the residents’ association by chucking empty wine bottles in the bin meant for paper and packaging, and perishable rubbish in the glass collection bin.”

Houellebecq doesn’t cut his protagonist any slack either. After all, Florent-Claude’s revolt is as ridiculous and as devoid of meaning as the superficial eco-friendly types, who think they’re doing their part in saving the planet. Is this what revolt looks like in the modern world? Throwing your bottles in the wrong bin? What a banal and meaningless rebellion. (Compared to the very real dairy farmer rebellion, in which Florent-Claude’s friend Aymeric participates—foreshadowing, as many others have already pointed out, the gilets jaunes movement).

Just as he does in his earlier novels, Houellebecq once again explores what excesses a culture conceives when it becomes bored with its own freedom.

And, of course, it wouldn’t be a Houellebecq novel without sex. In the era of #MeToo, a more self-conscious writer might have shied away from the topic or—at the very least—toned down some the scenes, but instead Houellebecq finds a way to ramp it up. In one scene, Florent-Claude discovers videos of his Japanese (soon-to-be ex) girlfriend Yuzu having sex with multiple people in his house while he’s at work, and in one particular video, even participating in what is described as a, “mini-canine gang bang.”

In the sexual marketplace of Houellebecq’s other novels, there have always been winners and losers, but never Dobermanns and bull terriers before. I don’t think he expects the reader to take these scenes all that seriously. One gets the sense he is entirely aware that he’s trolling us. You can almost hear the echo of his laughter behind each sentence. He wants us to laugh with him, and we do. At the same time, there is still worthwhile commentary here. Just as he does in his earlier novels, Houellebecq once again explores what excesses a culture conceives when it becomes bored with its own freedom. In The Elementary Particles, he uses the modern archetype of the rock star, for whom sleeping with a lot of women becomes so routine, that he turns to murder to get his kicks. In Whatever, prefiguring incels by 20 years, he uses a frustrated virgin to arrive at the same conclusion. Like money, too much or too little can lead to a lot of dissatisfaction, and, in Houellebecq’s novels, that sometimes means violence.

But where Houellebecq may seem to be purposely trying to shock or troll the reader at times, his provocations are necessary, and, in this novel—like all his novels—what his characters really want is fulfillment. Mostly, they are alienated, lonely people, haunted by the past, who often regret the trajectory of their lives, as Florent-Claude does: “It isn’t the future but the past that kills you, that comes back to torment and undermine you, and effectively ends up killing you.”

Unlike their creator, Houellebecq’s characters aren’t punk. They don’t revel in shock. If anything, they want to belong. They are citizens of the modern West, who have been mangled by their attempts to build a meaningful existence in a culture that constantly manufactures discontent. Love, spirituality, authenticity, all are unattainable for Houellebecq’s characters, who have abandoned hope like that mezzanine in the failed architect’s house. Except the house is their life. And they are the failed architects.

Clint Margrave is the author of two poetry collections Salute the Wreckage (2016) and The Early Death of Men (2012), both published by NYQ Books. His debut novel, Lying Bastard, is forthcoming from Run Amok Books in the spring of 2020. He has also written essays for Areo and Quillette, among others. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Brilliant review… far better than what The Guardian printed about Serotonin. But then again, the politics that has infested the Guardian is exactly the same politics that Houellebecq is seeking to destroy