“You can’t take politics out of the judicial process because judges are human.”

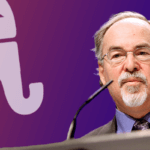

Randy Barnett is the Director of the Georgetown Center for the Constitution and serves as the Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Legal Theory at the Georgetown University Law Center. An expert in constitutional law, Barnett has written several books on the subject, including Restoring the Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty and Our Republican Constitution: Securing the Liberty and Sovereignty of We the People. Barnett appeared before the Supreme Court in the case Gonzales v. Raich, which challenged Congress’ authority to criminalize the use of homegrown marijuana in states that allowed its use for medicinal purposes. Today, Barnett joins Merion West and Erich Prince to discuss his experience arguing a case before the Supreme Court as well as new challenges that the Court faces today.

Professor Barnett, thank you for joining us today. To get started, what are some of the main differences between standing before a normal court, as opposed to being before the nine justices Supreme Court of the United States?

First off, there are nine of them, which differs from the three you get in the Court of Appeals and the one you face in District Court. You have nine potential people asking you questions which you need to satisfy. You are doing so with several hundred people standing behind you, while there is a jury box to your left recording what you are saying. Also behind them, you have someone drawing you for the artist’s rendering of your argument.

That plus the fact you are standing within inches of your opponent proposing oral arguments, who in my case was sitting to my right, is quite remarkable. You are very close to the justices. In fact, they sit in a semi-circle, and you are in the center of it. In order to speak to the justices, you have to turn to your left or right to face them.

On the subject of nine potential justices asking questions, I understand you were not there on that very infrequent occasion when Justice Thomas asks a question.

I was not there when he asked questions. In fact, when I did argue he didn’t ask me any questions. It would have been very helpful if he had, because the only people who asked me questions in the Raich case were justices who ultimately voted for the other side. Therefore, all of their questions were antagonistic for me. We had three votes for us on our side, Chief Justice Rehnquist who was sick, Justice O’Connor who didn’t ask questions, and Justice Thomas who rarely asks questions. Therefore, I got no help from the justices. Justices do help as well as give hard questions. They help the side that they are on. I only got questioning from the six judges who voted against us.

So it must have really felt like you were on the hot seat?

I was definitely on the hot seat. Although since then, I have seen people get it worse than I did. I will say Justice Kennedy got a little hot under the collar, and Justice Souter got a bit excited. But generally speaking, they are all very mannered, and it is collegial when they ask you questions. I have seen them be less collegial in high profile cases, but, in my case, they were pretty tame. I should say it is the substance of what they are asking you and the need to respond so effectively that is challenging—not their tone of voice.

I would imagine that in answering the questions a Supreme Court justice, you are engaging in a very elaborate and nuanced understanding of the law.

It is nuanced, but it is not more nuanced than you would expect it to be. Because by the time you argue in front of the Court, you have been involved with the case for a long time. I also did three moot courts before I did the real thing. So it is no more nuanced or sophisticated than you are prepared for. It is really that they are asking you the hardest questions for your side. It is that way no matter which side you are arguing. There are very hard questions regardless. Sometimes the answers you have aren’t satisfactory, and they come at you harder and harder. It is really like a contest; it is nuanced but that is not the problem. They ask you difficult questions that are designed to be difficult to answer, but you have to answer anyway.

You obviously come in prepared knowing the best arguments of the other side. Do you know the best argument they will present before they even say it?

Pretty much. You don’t exactly know how they will specifically respond to your first response. Even if you prepare for a question and you have a prepared answer. Once they give their response, it may not come out how it does in moot court. That is what moot court is for though. The moot court judges follow up on your answers to test you. In fact, in my first moot court, there was one important argument I had to respond to that I gave in front of the Court of Appeals, and it just didn’t work. I couldn’t deal with the follow-ups, and it really was going to be devastating if that was how it went in the Supreme Court, which would only be three weeks later. However, I found answers to that question in the next three weeks to escape devastation, which is what would have happened had I answered it the same way I did earlier.

In terms of medical marijuana, the decriminalization of marijuana, or even the decriminalization of other hard drugs in general, to what degree does public opinion affect the law, or vice versa?

I do think public opinion does matter. Even though the justices are supposed to be above politics and public opinion, they are still human beings. And we all live in the social and political world that is around us. So within that world, there is an acceptable range of positions for people to hold on any policy issue. That bleeds over into legal issues as well. So there is a left side of normal and a right side of normal, and as long as you stay within that guideline, then you are pretty safe. If you try to venture too far left or right, you will more likely get an unsympathetic hearing from the judges.

They are also restrained from what they can do legally. So it is an interaction of politically and legally accepted arguments. So you have to try and have both going for you.S

Switching gears a bit and given your work at Cato and in libertarian thinking, when it comes to questions of individual rights and freedoms in 2018, what are some of the current issues of concern for you? What rights or freedoms do you think may be in the crosshairs and at risk of receding?

I can think of two areas: economic liberty and the right to bear arms. In respect to economic liberty, the Supreme Court has set up a doctrine in which only rights that the Court deems to be fundamental get any protection. So judges have to deem a right to be fundamental. Through the way they determine that, no economic liberties are fundamental. Some personal liberties are, but economic liberties are not. Therefore, there is very little judicial scrutiny of laws that limit economic liberty.

On the other side, there is an enumerated right, the right to bear arms, that the Supreme Court finally recognized to be a fundamental right. Yet lower courts are not scrutinizing restrictions on that right to the degree they have in the past, or as they have for freedom of speech or abortion. So this particular freedom is not being treated with the same degree of judicial protection that other rights have been. This is partially the fault of the Supreme Court, that has not done anything to discipline or rein in lower courts that are essentially allowing this right to be regulated in ways others have not.

Do you think there is a particular set of reasons that have made the Second Amendment stick out among other issues?

First of all, there is a considerate part of the electorate that really dislikes this right. Lower court judges who are a part of the electorate find ways to uphold laws they think are good laws because they believe it is a valid exercise of public policy on behalf of local lawmakers. There is also the lack of will from the Supreme Court to push back and keep lower courts in line. I do think this is a right that is more controversial than the right of freedom of speech, even though in some respects today that right is also controversial as well.

So you can’t take the politics out of the judicial process?

You can’t take the politics out of the judicial process because judges are human. There is a certain amount of give in the joints of what they can and cannot do under the laws they are enforcing or the Supreme Court doctrine they are supposed to be applying. That is true at the lower court level but doubly true at the Supreme Court level, where justices do not have to follow precedents, if they don’t really want to. Lower courts try harder to follow precedents than the Supreme Court does because they feel less empowered to change that. They are not supposed to change what the Supreme Court is saying, where the Supreme Court itself can always change.

Back on the topic of the Supreme Court, I want to quote something you said in October in reference to Aaron Belkin saying we need more seats on the Supreme Court. You said: “Under our current institutions, we have a Supreme Court that has had a stable number of justices for a very long time. But now, because finally it may be the case that the Left has lost a majority of the court, because of that and only because of that, we’re now supposed to change the court so we can ensure the Left wins again.”

This issue of court-packing has some historical precedent. Can you speak more on the history of the term and why it’s back in the spotlight?

Court-packing is not a legal term, so you have to figure out what you mean by it. What some people interpret it as is when one political party has judicial nomination power, and they choose judges that are amenable to that party. That is not court-packing. It is called court-packing, but that is not what it is. We have a system at the federal level which anticipates that a politically-elected president is going to be selecting judges that are confirmed by a politically-elected Senate. So there is going to be a political valence to the judges that they pick.

So as long as there is a divide between the two parties of what the proper roles of judges are and what the proper role of judging the Constitution is, there is going to be a difference in judges picked by Democratic and Republican presidents.

Is that political charge two-fold in that perhaps a politically-appointed judge might feel a certain loyalty to share the positions of the president who appointed him or her?

I think there is very little partisan loyalty as far as judges go across both parties. I feel that, generally speaking, this is how they feel. However, they are chosen by a particular president and party because they share a particular approach to the Constitution and the job of judging. They can be predicted to act upon that preexisting judicial philosophy that they have, which I would not call ideology. They will predictably act on the basis of the judicial philosophy, which led to them being nominated.

As long as the two parties are picking people with different judicial philosophies, those judges can be expected to act differently when they are called upon to rule. None of it is done out of personal loyalty to the president or party that nominated them. I don’t think that is how most of them think.

That is not court-packing though. That is how the system was designed when it was set up. Eventually Franklin D. Roosevelt got to name all nine Supreme Court justices, and he picked justices that would have been friendly to the New Deal. As a result, he got what he wanted. That is what the system contemplates.

The original meaning of court-packing is to expand the number of judges so that you can pick your own judges and water down the majority of justices who are seated against you. That is what Roosevelt proposed, which was called the Court-Packing Scheme. As long as a judge was over a certain age and didn’t retire, he would get to nominate another judge. That was even unpopular with the Democrats in Congress when he had a supermajority in both houses, and they opposed the scheme.

Now some people are proposing to try it again. They don’t seem to realize that if Democrats can do it, so can Republicans. Both sides tend to have similar tunnel vision, but today I think it is fair to say that progressives are much more prepared to question or get rid of any Constitutional structure that stands in the way of their victory.

They blame the electoral college and the fact that each state regardless of population has two Senators for losses. There is a filibuster that they long supported until it was used by Republicans, and then they got rid of the filibuster. Whenever there is a barrier in way of what they want, they think it should be eliminated in favor of a majority will, until the minute they don’t have the majority. Then they become in favor of filibustering and lawsuits that invalidate popular laws. They are happy to do that when they lose in the electoral process.

Right, I have heard some self-reflective Democrats admit that they would have been very in favor of the electoral college in 2004 if John Kerry had won Ohio and thus the electoral vote, even if he had lost the popular vote to President Bush by almost three million votes.

Yes, exactly. And I think it is important for people to realize that the number of Supreme Court justices is not fixed by the Constitution, and therefore it is within the power of Congress to set the number of justices. That number has ranged from six to ten over the years. We have had nine justices for a very long time, but that can be changed by a simple statute that is passed by both parties of Congress and signed by the president.

When both Houses are held with a majority by the same party they can change the number of justices, and that is not unconstitutional. We have had nine since around the end of the Civil War. It briefly went up to ten before shifting back down to nine. However, we did start off with six.

Lastly, to what degree was the Kavanaugh hearing the culmination of a long-standing effort to upset the nomination of Republican judicial nominees? Is this something that was a singular event or something that had been building and taking place for a while?

I would say it is the latter. For a very long time, there has been an effort to personally demonize Republican nominees that we have not seen go in the other direction. I am not saying that no one in the general public tries to demonize nominees, but it has not been true in the Senate Hearing.

I think, in a way, Republicans have not opposed Democratic nominees on the basis of judicial philosophy as much as they should have in the past. To oppose a nominee on the basis of judicial philosophy is not the same thing as trying to personally destroy them from issues that came up in their adolescence.

That is something we have not seen before. We did see this with Robert Bork, but it didn’t register pretty much because most of the opposition to him was his judicial philosophy. While most people are not old enough to remember this, they were trying to get Bork’s video rental records and figure out what videos he rented to go against him personally. Then in the Thomas nomination, it was marred by the Anita Hill allegations, which came about as a result of a leak from Democratic staffers to the press following the closure of the hearing. That information was all in possession of the Democrats during the hearings, which were led by Joe Biden. But nothing was done about it by the Democrats because it wasn’t something they wanted to get into.

This idea of personal destruction as a political move towards Supreme Court nominees is an increasing trend, and it really was the pinnacle of this with the Kavanaugh hearings. Once again, the Democrats were in possession of this information, they deemed it not suitable to proceed with or mention it to their Republican counterparts until it was leaked following the closing of hearings. That’s when everything hit the fan, and it was very analogous to the Thomas hearings.

The difference was during the Thomas hearings the Democrats did inform the Republicans about what was going on, and they had an investigation prior to concluding the hearings. This time they kept it to themselves and wanted to wait to have an investigation on the fly, which was hard to deliver at that point

Thank you for speaking with us today, Professor Barnett.

Absolutely. Thank you for having me.