“Charles Darwin himself was quite wary of the metaphysical or religious implications of his discoveries.”

“Books lie, he said.

God dont lie.

No, said the judge. He does not. And these are his words.

He held up a chunk of rock.

He speaks in stones and trees, the bones of things.”

– Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

Was Darwin wrong? Did life really arise and evolve as a consequence of blind natural forces?

For most evolutionary biologists (and most modern educated people) what we call Darwinism is, “settled science.” Darwinism is nothing less than one of the great intellectual pillars of the modern, secular world.

But skeptics persist, and not simply religious fundamentalists. A small but perhaps growing minority of evolutionary biologists and other scientists insist that Darwinism as commonly understood is incapable of explaining the phenomenally complex nature of the universe in general and of living forms in particular. The theory of Intelligent Design argues that the closer we look—for example—at the molecular biology of a living cell, the more it appears to have been designed. But designed when and designed by whom? And how is asking these questions at all amenable to science?

To affirm that life on earth has been around for hundreds of millions of years is well supported by scientific evidence. To assert that biological species seem to have evolved from a common ancestor is also well-supported by scientific evidence. These kinds of facts are not particularly in question, even by advocates of Intelligent Design.

But how the facts are interpreted is open to question. To assert that all life evolved by blind chance or to assert that life emerged by design are not so much scientific assertions as they are forms of metaphysical speculation.

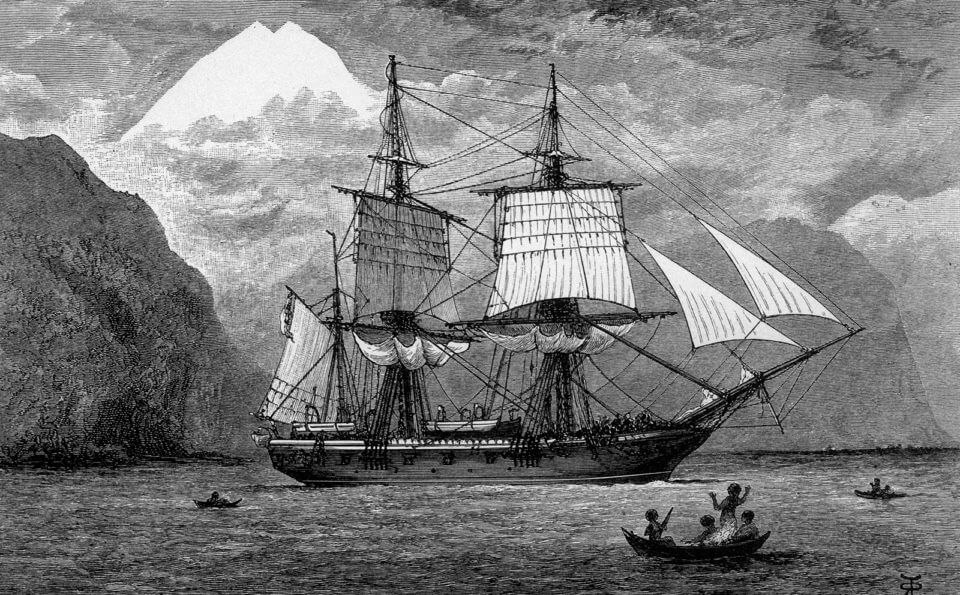

Charles Darwin himself was quite wary of the metaphysical or religious implications of his discoveries. In a letter to American botanist Asa Gray, written shortly after publication of On the Origin of Species, Darwin wrote:

“With respect to the theological view of the question. This is always painful to me. I am bewildered. I had no intention to write atheistically. But I own that I cannot see as plainly as others do, and as I should wish to do, evidence of design and beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world.”

Yet, in the same letter, Darwin continues:

“On the other hand, I cannot anyhow be contented to view this wonderful universe, and especially the nature of man, and to conclude everything is the result of brute force…”

Darwin speculated that perhaps a deity got the universe rolling with a grand design but left the details to chance. But he could not fully shed his confusion on the matter. In another letter to the theistic Gray later that year, Darwin wrote:

“But I grieve to say that I cannot honestly go as far as you do about Design. I am conscious that I am in an utterly hopeless muddle. I cannot think that the world, as we see it, is the result of chance; and yet I cannot look at each separate thing as a result of Design…Again, I say I am, and shall ever remain, in a hopeless muddle.”

Darwin’s theories did, indeed, carry greater civilizational implications. How the question of the origin of life is answered by a civilization inevitably reveals a great deal about that civilization; where we come from tells us who we are and where we might be going.

Some evolutionary biologists still look at questions of evolution as strictly questions of science, insisting upon science’s metaphysical neutrality. This seems to be a minority view; most scientists apparently feel science itself logically leads to a more atheistic view of reality. Richard Dawkins is a particularly articulate and opinionated atheist who is quite contemptuous of what he calls, “the God delusion.” Darwinism, he insists, allows him to be, “an intellectually fulfilled atheist.” This, then, is not a fringe battle in some obscure pocket of science but a titanic struggle for who we are as human beings.

The persistence of the Design/Chance debate suggests that the problem of biological evolution is but a particular subcategory of the greater problem of discerning the nature of the universe itself. The psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist addresses the issue this way:

“The most fundamental observation that one can make about the observable universe…is that there are at all levels forces that tend toward coherence and unification, and forces that tend toward incoherence and separation.”

Which is to say, existence is paradoxical. The nature of this paradox is a kind of insoluble conflict or polarity which can be described in many ways: design/chance, permanence/impermanence, order/disorder, energy/matter, growth/decay, subject/object etc. etc.

Often, we, humans, seem to be uncomfortable, if not frightened, when we find ourselves confronted with such paradoxes. We may even become muddled. Much of human thinking over the millennia has been dedicated to resolving these paradoxical polarities. They may be ultimately insoluble, yet we insist upon solving them. Indeed, every society is itself a kind of solution to these paradoxical questions.

For centuries in the West, our muddle was resolved by presuming and accepting a kind of transcendent order or design of the universe. Christianity told us where we came from, who we were, and where we could go (if we behaved ourselves), or where we would go if we didn’t. Nature was fallen, corrupt, and ephemeral, but our true destiny was somewhere else free of conflict, decay, and suffering. This static and hierarchal Christian universe sustained and ordered life for centuries. But, ultimately, like all forms in nature, it became sclerotic, desiccated, and finally unbelievable. The forces of disunification and change reasserted themselves.

By the time Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, a great metaphysical shift was well underway. Well before Nietzsche, Hegel had already talked of the death of God and the end of history. Even by 1820, Percy Bysshe ShelleyPercy Shelley described the world as filling with, “doubt, chance and mutability.” If the designed universe is false, then must not the chance universe be true? No one seemed to heed Nietzsche’s warning that such categories are, at best, useful fictions. So the designed universe dissolved into the chance universe, and most would be swept along in the great shifting tide.

Darwin’s muddle reflects a man caught in the middle of this great cultural shift. Charles Darwin, that greatest of empiricists, bears witness to the raw spectacle of paradoxical nature. He sees clearly manifestations of design, and he sees clearly manifestations of chance. Reading Darwin’s letters to Asa Gray reveals a man transfixed by the blinding spectacle of contrary forces. Darwin is a deer in the headlights: He can’t move forward; he can’t move backward.

The young science of evolutionary biology would be absorbed into the metaphysics of secular materialism. And, thus, Charles Darwin became a Darwinist.

The great tide of metaphysical interpretation would sweep over Darwin’s confusion. Paradoxical reality would be again be “solved”; only this time the forces of incoherence and chance would triumph. We may have lost access to Heaven, but we gain power over nature. With profound growing pains, a whole civilization would fabricate itself out of its ideas of a chance universe.

And in one of the great ironies of history, Darwin’s muddle would be ignored and forgotten. His ideas about the origin of species would be defined as the ultimate affirmation of the chance universe. The young science of evolutionary biology would be absorbed into the metaphysics of secular materialism. And, thus, Charles Darwin became a Darwinist.

Darwin was not the only one to see paradoxical reality. There persists another type of empirical human being who acknowledges the paradoxical nature of reality—but who is not disturbed and who has no need to escape. Indeed, this type revels in conflict and paradox. These are the poets and artists, and they’ve been confronting paradoxical reality for millennia.

Poets are not intimidated by words like “design” and “chance” because they understand their poetic nature. They understand that they are distinctions made by human beings, which describe two aspects of one thing. Iain McGilchrist’s forces of coherence and unity exist simultaneously with the forces of incoherence and disunity. Wallace Stevens expresses this in a poem entitled “Connoisseur of Chaos,” which begins:

“A. A violent order is a disorder; and

B. A great disorder is an order. These

Two things are one.”

Disorder, spontaneity, or randomness are essential aspects of evolving life. But so are harmony, order, and pattern. Any viable form in nature is a dynamic of order and disorder. Evolving biological forms maintain and manifest dynamic and (more or less) harmonious relationships within their own physical bodies—and with their environments. Those organisms (or species), which fail to do so, are precisely those that perish, those that become extinct. The unfolding of these evolving relationships over the vastness of time—organic forms adapting to shifting climates, geology, other life forms etc.—resembles music, or dance, or poetry more than the dumb combination and recombination of various elements.

The great artists and poets understand the creative and exuberant powers of nature because they experience these same powers in themselves.

To abstract the seemingly random or spontaneous activity of a given gene or gene sequence from the whole dynamic process and to then determine that that aspect reflects the essential nature of biological evolution could hardly be called science. One might as well call a symphony the product of, “random sounds.” The modern Darwinist’s insistence on focusing on one aspect of a manifestly unified process tells us more about the transcendent powers of cultural prejudices of a given time than it does about the nature of biological forms.

The world is—as we experience it—an ever-changing and evolving symphony of energy and forms, what Nietzsche called, “…a monster of energy…eternally self-creating…eternally self-destroying.” All scientific terms and all biological classifications from “kingdom” to “species” are poetic descriptions of certain relationships.

The great artists and poets understand the creative and exuberant powers of nature because they experience these same powers in themselves. They are not just observers of nature; they are simultaneously participants. What may appear to others as contrary forces are experienced as unified and necessary. For a great creative mind, there are no paradoxes to resolve, no causes to uncover. Walt Whitman in his “Song of Myself” simply bears witness to experience:

“There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now;

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.

Always the procreant urge of the world.

Like life itself, a work of art is some harmonious relationship of “opposite equals.” A great poem or painting or symphony “lives” because it embodies the dynamic forces of life itself. And as Walt Whitman himself understood, there is nothing discovered by science that conflicts with a poetical understanding of reality. Rather, “[i]n the beauty of poems are the tuft and final applause of science.”

Modern science has become our way of knowing reality, yet it seems to lack an understanding of its own poetic nature. Scientists—unlike poets, but more like theologians—are not content with simply observing and describing reality; they insist on explaining reality.

Since Darwin, evolutionary biologists claim to have discovered the cause of evolutionary change when, in fact, all they’ve done is observed certain relationships.“ For the scientific method,” wrote Albert Einstein, “can teach us nothing else beyond how facts are related to, and conditioned by each other.” Scientists confuse their very sophisticated ability to elucidate relationships with elucidating causes. Nietzsche calls this “the error of imaginary causes.” The word “cause” can be a useful term to describe a particularly strong relationship. But, taken too literally it tends to abstract elements of nature from their embeddedness in a greater totality.

This tendency to distrust immediate experience and posit a reality (or cause) behind appearances is clearly manifest in the concept of “natural selection.” Natural selection is described as the “mechanism,” which “drives” biological evolution. This reflects a nineteenth century mechanistic billiard ball understanding of reality. Natural selection as cause of evolution is an intellectual crutch for those who seem to have a crippled sense of themselves as creative powers in a creative universe.

Arguably Darwin’s great and enduring contribution is not that he discovered some “hidden cause” to explain the origin of species—but that he documented the dynamic nature of biological change. Biological organisms were not created all at once; rather, they “naturally select,” which is to say they maintain an ever-evolving and dynamic relationships with their environments.

Like natural selection, the use of the word “random” to explain evolutionary processes betrays the same kind of mechanistic unpoetic understanding of reality. Among orthodoxical Darwinists, the word random has become synonymous with the elemental processes of nature itself. To describe the workings of nature as anything other than random is apparently not only heretical but “unscientific.”

What seems to have happened in orthodox Darwinism is the little word random—like an opportunistic virus—has inserted itself into the whole science of evolutionary biology, parasitizing, and finally dominating its host. The word random has come to suggest a transcendent cosmic principle or what William Blake called a “mental deity.”

Orthodox Darwinists’ insistence on the creative powers of random processes leads them to conclude that the order and harmony we actually observe arose from what we do not actually observe. Again, what we observe and experience all around us, all day every day, is a dynamic of order and disorder…so where are these purely random forces, where is this random universe? Typically, it is a priesthood that would have us ignore our own experience and insist upon their authority over some specialized knowledge.

This materialistic Darwinism has dominated for more than a century-and-a-half, but its own explanatory power may be waning. Proponents of Intelligent Design insist that the very complexity of life cannot be explained by essentially random mechanistic processes. But Intelligent Design is perhaps a poor choice of words that tends to shift attention away from the thing (or event) observed to some pre-existing designer. You do not have to introduce the notion of an Intelligent Designer to acknowledge the existence of order and pattern in nature. The universe may be apprehended, as it was by Albert Einstein among many others, as embodying intelligence insofar as the human mind can apprehend order and harmony. For Einstein, doing science was nothing less than an attempt to understand this intelligence. Sticking to what we actually experience, the universe is better described as creative rather than created.

Civilizations get to interpret reality, but they do not get to make reality. The paradoxical universe did not go away and will not go away. Both the Christian and modern secular interpretations are ways of separating and protecting ourselves from paradoxical reality. The Designed universe has been displaced by the Chance universe, and we tend not to notice that these might be merely two aspects of one reality. Darwin noticed—and then we forgot that he noticed.

Yet the debate persists: Some of us insist on Design; some of us insist on chance. The persistence of the debate itself seems to suggest—regardless of what we presume or desire—that we have been participating in paradoxical reality all along.

Chris Augusta is an artist living in Maine.

Chris Augusta:

Calling Evolutionary Biology “Darwin” or “Darwinism” is itself a gross over-simplification. modern Evolutionary Biology includes explicitly non-Darwinian mechanisms such as Genetic Drift/Neutral Theory.

May I quote a judge who more directly addresses this issue:

“In making this determination, we have addressed the seminal question of whether ID is science. We have concluded that it is not, and moreover that ID cannot uncouple itself from its creationist, and thus religious, antecedents.” — Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District

Intelligent Design Creationism has minuscule support from the scientific community. This can be easily demonstrated by the fact that the number of scientists only named a variant of “Steve” (Stephan, Stephanie, etc) signing a petition supporting evolution outnumbers the number signing a petition questioning it. ID’s most prominent supporters include far more theologians, philosophers and lawyers than scientists. That it is a form of creationism can easily be demonstrated by its close resemblance to the earlier idea of Progressive Creationism.

A Scientific Theory does not ‘argue’, it explains. As ID offers no explanation, just the bald assertion that “certain features of the universe and of living things are best explained by an intelligent cause, not an undirected process such as natural selection”, it is not a scientific theory.

IDC prominently includes a number of Young Earth Creationists who deny that “life on earth has been around for hundreds of millions of years”. It also prominently includes those who deny Common Descent — one of its most prominent forums is one titled “Uncommon Descent”.

Creationism, including ID, works by cherry-picking and misrepresenting the facts that it chooses to interpret. A recent and prominent ID book was summarised as “compromised by [its author’s] lack of scientific knowledge, his “god of the gaps” approach, and selective scholarship that appears driven by his deep belief in an explicit role of an intelligent designer in the history of life” by one of its own cited sources.

Nietzsche introduced the idea of perspectivism: in the final analysis, all we really have is a manifold of interlocking perspectives. For example, consider the following toy model. If humans are small finite, represent each possible human perspective by a small non-empty subset of {1,…,n} where n is a large natural number. Then, there are minimal perspectives, but no maximal human perspective. Still, there is an ideal finite perspective which sees everything! If n=infinity, then there is still an ideal infinite perspective which sees everything! (God’s eye-view!) If one accepts the standard quantum logic, then one has a manifold of perspectives which cannot-by Gleason’s Theorem-be embedded into any single perspective! There are now maximal perspectives, but no universal perspective!

http://alpha.math.uga.edu/~davide/