Note from the Publisher: This piece belongs to the Merion West Legacy series, referring to articles and poems published between 2016 up to Spring 2025.

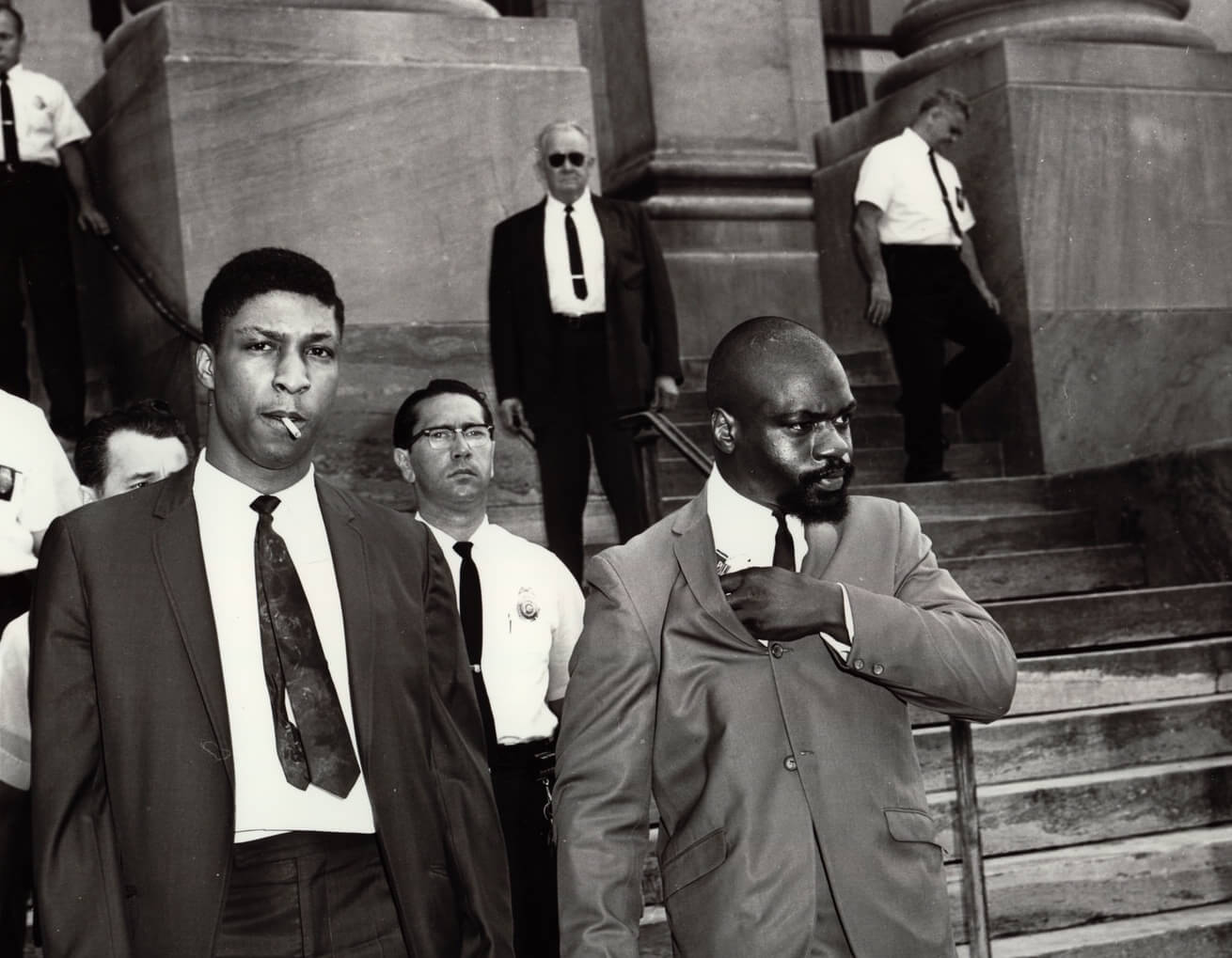

The Real Truth of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter

“To DeSimone and his acolytes, two cold-blooded murderers were freed. To our system of justice, two persons, their innocence always in question, were unfairly tried and convicted.”

Timeless reading in a fleeting world.

Journalism

Commentary

Poetry

Merion West is an independent publisher, celebrating the written word since 2016.

Join Now

$3/month Free

If unable to pay, click here.