Note from the Publisher: This piece belongs to the Merion West Legacy series, referring to articles and poems published between 2016 up to Spring 2025.

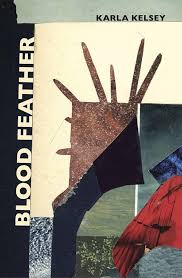

Fierce Lyric in Karla Kelsey’s “Blood Feather”

“Blood Feather stages scenes of both unexpected victory and chronic defeat in the three featured lives, while allowing us to imagine an alternative history for these women, had they been listened to and given latitude to exercise their rightful prerogatives in the culture at large, rather than retre

Timeless reading in a fleeting world.

Journalism

Commentary

Poetry

Merion West is an independent publisher, celebrating the written word since 2016.

Join Now

$3/month Free

If unable to pay, click here.