“On the House does not provide a clear answer, but, if one reads carefully, one might find that Boehner’s short-term pessimism and long-term optimism are both warranted.”

“There are people we are electing who will destroy this country if we aren’t careful.”

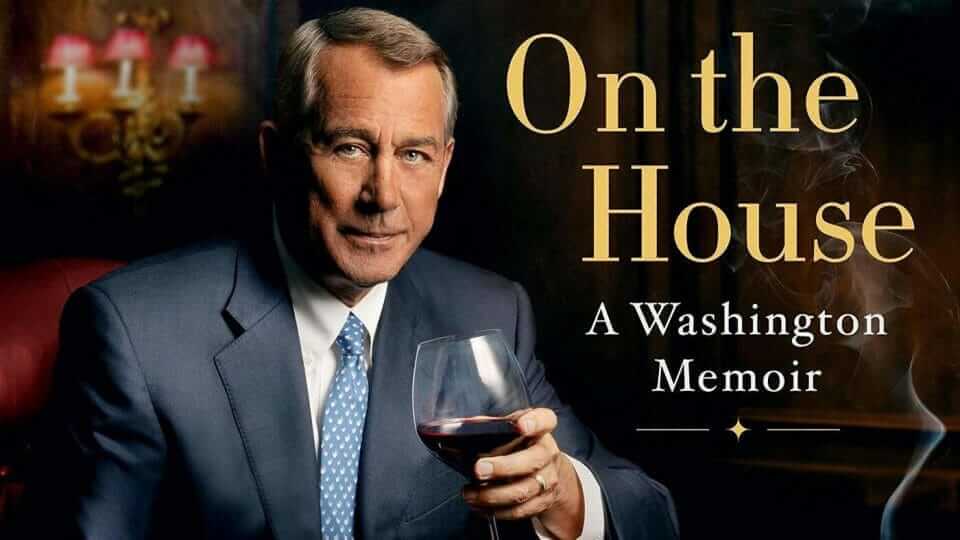

—John Boehner in On the House: A Washington Memoir

Dire warnings like these are sprinkled throughout the expletives and laugh-out-loud anecdotes filling former Republican Speaker of the House John Boehner’s new book On the House: A Washington Memoir. But so are lines like this one: “I want this book to be filled with hope. Because I do think we can solve these problems. I believe in this country and in our system.”

Throughout the course of his book, Speaker Boehner waffles between buoyant optimism and utter dread over America’s political future. Readers will leave entertained but also a bit confused. What does John Boehner, the scrappy son of a bartender from Ohio, really think? Is America doomed, or is it not? Will we muddle through like we always have or fall flat on our collective face? On the House does not provide a clear answer, but, if one reads carefully, one might find that Boehner’s short-term pessimism and long-term optimism are both warranted.

The roots of Boehner’s more dour, pessimistic takes in On the House are in the rise of the “political terrorists.” Whether it is “The Squad” on the Left or the Freedom Caucus-turned-MAGA base on the Right, Boehner detests those in Congress “peddling chaos and crisis so that everyone keeps paying attention to them.” Boehner’s time as Speaker coincided with the strengthening of the right-wing media outrage-peddling machine, so he has seen up close and personal how the so-called “political terrorists” have hijacked our politics.

In particular, Boehner laments how they have driven the governing process into the ground. Boehner is no moderate; he was elected in the early 1990s and soon ascended to Republican leadership alongside Newt Gingrich. He is unapologetically conservative, particularly with regard to finance, regulation, and taxation. But he also has a pragmatic streak; he longs for “the old-school congressional tradition of actually making deals instead of running around trying to stop everything in its tracks.” Boehner points back to his political idol, President Ronald Reagan, as an example of how to mix conservative principles with pragmatic politicking and legislative deal-making.

The political terrorists of Washington are not the underlying problem. We are.

But the folks back home and the media figures they so faithfully watch and listen to do not seem to be crying out for incremental progress, compromise, and good-faith debate and give-and-take in Congress. Looking back on the Obama years, Boehner laments how Fox News and talk radio hosts like Mark Levin and Rush Limbaugh ginned up so much right-wing rage at President Barack Obama that it made basic governing tasks nearly impossible:

“All of this crap swirling around [in the right-wing media] was going to make it tough for me to cut any deals with Obama as the new House Speaker. Of course, it has to be said that Obama didn’t help himself much either. He could come off as lecturing and haughty. He still wasn’t making Republican outreach a priority. But on the other hand—how do you find common cause with people who think you are a secret Kenyan Muslim traitor to America?”

Rather than standing up to these outrage peddlers, too many of Boehner’s colleagues in the House played right along. Rather than working hard on their committees, trying to pass significant pieces of meaningful legislation (which would, of course, have to be bipartisan, notes Boehner), or making tangible impacts on the economic health of their districts, too many of Boehner’s colleagues primarily focused on booking appearances on Fox News. Governing was less important than ideological purity and partisan outrage. Boehner’s distaste for some of the members of the Tea Party class of 2010 drips through the page as he writes: “Incrementalism? Compromise? That wasn’t their thing. A lot of them wanted to blow up Washington. That’s why they thought they were elected.” After all, “they didn’t really want legislative victories. They wanted wedge issues and conspiracies and crusades.”

And conspiracies and crusades they achieved, during both the Obama presidency and, of course, during the Trump years.

Boehner seems well-aware that these representatives’ constituents back home—everyday Americans—were the ones allowing the “legislative terrorism” that took down his Speakership (and propelled President Donald Trump to the White House) to persist. Boehner writes: “Part of the problem, if we are going to be really honest about it, is that we the people put up with all this malarkey. We prefer the easy outrage over focusing our attention on tough questions that don’t have five-second solutions.”

But many of us are not merely “putting up” with it; we’re asking for it.

The hard truth is that the “reckless a—holes” like Ted Cruz with whom Boehner served in Congress are more symptoms than causes. By looking back on his political life, Speaker Boehner reminds us that our political “leaders” are, in fact, “followers.” As Boehner escorts readers back into the “room where it happens,” it becomes clear how constrained he and his fellow politicians often are. The political terrorists of Washington are not the underlying problem. We are.

And Boehner clearly understands this, which is why as he recounts the 2013 government shutdown, the failures of immigration reform, and the death of his deal with President Obama to strike a grand bargain on the national debt, he often mixes in an aside or two about how it is up to us readers—everyday citizens and voters—to change the tenor of Washington by electing more reasonable people:

“Whether it’s the economy, or healthcare, or immigration, or national security, no meaningful progress will ever be made unless we elect serious people who truly want to make that progress. Some may say that’s surrender, and that if we just elect enough people to office who think like us, eventually we’ll be able to do everything our way. Well, if you think like that, chances are you’re part of the problem.”

Still, Boehner refuses to lose hope in Americans or in our capacity for self-government. He draws on his love of golf in particular and lessons from role models like his high school football coach Gerry Faust and former President Gerald Ford to argue that all is not lost—that our dysfunctional, outrage-ridden political moment could prove somewhat fleeting. Faust, for example, “taught [Boehner] to never quit,” and one gets the sense that Boehner has not quit on the American people just yet. Indeed, he closes by remarking: “I have just as much faith in America now as I’ve ever had.”

The preceding 250+ pages of political failures and lamentation of Congress’s growing aversion to deal-making and actually governing would seem to cut against such bright-eyed optimism, but perhaps Boehner is correct to remain hopeful for the long term. Even if we might not seem entirely up to the challenge of self-government right now, Americans have proven uniquely adept at course-correcting and muddling through in the past. There is reason to believe that a sufficiently informed and energized segment of the Left, Right, or middle may rise up and help push our politics in a more sane direction before the ship of state sinks.

After all, if this battle-hardened Washington politician can remain bullish on America’s prospects, maybe we all should.

Thomas Koenig is a recent Princeton University graduate who will be attending Harvard Law School in the fall of 2021. Follow him on Twitter @TomsTakes98