“Worst of all, it isolates us.”

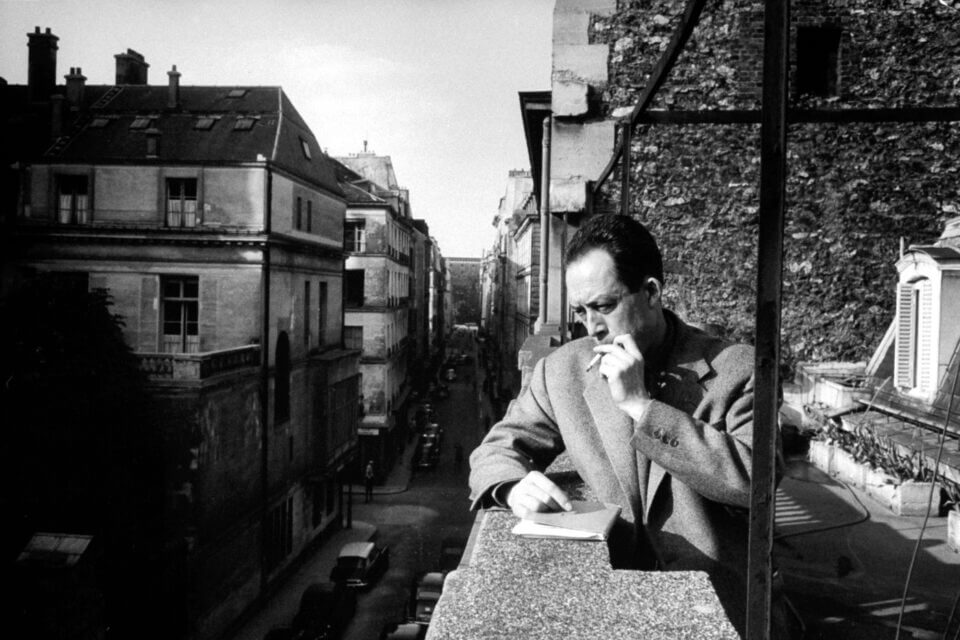

Disease is a horrid thing. It admits no distinction between the rich and poor, man and woman, old and young, and could take any of us at any moment. As Albert Camus—for one—knew, it is insidious. It works its way into our daily lives, wearing us down in a double-punch: exhausting us while also making rest impossible. Worst of all, it isolates us. It cuts us off from those around us, and we grow fearful of the simple act of association as if we are guilty of some crime just by standing side-by-side with others.

Of course, Camus was not writing only about disease. His 1947 book The Plague (la Peste) was, in part, an allegorical work on the oppressive power of totalitarianism and his experiences as a Frenchman during the early 1940s. What Camus depicted most accurately was the silent power of the National Socialist regime and its project of isolation; just as with the Cheka, the NKVD, and the KGB in the USSR, the Gestapo throughout the Nazi regime made clever use of informants. Throughout its existence, the actual size of the organization was much smaller than most citizens thought. The Gestapo ensured that the fear of the Other was inculcated through a program of terror and control. Members of the Gestapo, for instance, would appear in the dead of night and in full public view, taking away those who dared to resist the regime. As a result, no one knew whom they could trust, so, in turn, they trusted no one.

This isolation, Camus shows, was not achieved through obvious measures of force, such as a curfew or the control of movement. Rather, it was reached through inculcating a culture of fear of the Other, for what they might be or do to us. This goal could only be achieved by people who were, in fact, deeply aware of the fundamentally social nature of human beings; as Georg Hegel argued, we come to know ourselves through the Other, a morally autonomous being over whom we have no claim of authority or control, but out to whom we extend our Will and through whom we return to understand that Will’s limits. If we cannot engage in this eternal return (not, to clarify, as Friedrich Nietzsche understood the term) of our Will through the Other, we cannot learn about ourselves and cannot develop into a full person. Thus, we become mere bodies, essentially undifferentiated from any other body and, therefore, disposable.

Hannah Arendt wrote, in her 1951 work The Origins of Totalitarianism, a penetrating analysis of the concentration camps that highlighted their project of depersonalization. It was in the camps, Arendt argued, that the full project of the totalitarians was revealed. Beginning at the outset, all inmates were stripped of their external expressions of their selves, being undressed and shaved (in a specifically scientific manner, they were “deloused”), and, as they were ground through the unrelenting system of camp “life,” they were isolated so radically that they lost their personhood and—with it—their unique selves. They became, as Arendt noted, little more than bugs or vermin, who possessed no autonomous and unique selfhood and could be disposed of without a moment’s hesitation. They were no longer human, so, in this way, what the totalitarians were doing was not quite murder.

The totalitarians, who spread their system of fear throughout populations, knew how isolation went further than merely the denial of personhood and the disposability of the individual. They knew that when the individual loses his capacity of knowing himself through the Other so too disappears the realm of public action and the spontaneity of the public world. When I cannot reach out and touch the person beside me, either physically or metaphorically, I cannot form lasting bonds. With the death of the public realm comes the death of spontaneous social action and, also, the death of politics.

Disease is much the same as totalitarianism; indeed, that was Camus’ point. It is silent, insidious, and arbitrary; sure, some might be more susceptible to falling foul of its cold inevitability. However, most importantly, it rules through fear. The instability of the moment, the uncertainty of action, the unsure footing the individual stands on impedes both his capacity to think and his capacity to act. Any given action can no longer be trusted to be acceptable; even if something were allowed a few days before, it might suddenly not be. All the while, the silent monster makes no comment and watches implacably at the individual’s frustration.

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) has spread across our social lives in an uncompromising manner. In many ways, it has been aided—the entire time—by mistimed decisions, or lack thereof, and by politicians across the world. But the cruel inhumanity of this disease has been felt most keenly when it comes to our connections with others. The massive rise in mental health issues is not merely related to our inability to use the fitness center, go to the pub, or watch a film in the cinema; indeed, all of these are replicable in our isolated existences in the simple mechanisms of what they involve. We can exercise at home; we do drink alcohol at home; we have plugged ourselves into Netflix, Amazon Prime, BritBox, and enough streaming services to give Aldous Huxley himself a headache. However, what makes them feel so eerily strange is that we do them alone; there is no public sphere in the privacy of our own homes—and that is the salient point.

We find our humanity in the people around us. We know who we are by knowing who we are not, and we discover our shared fate in the public world that exists between each person. The longer this disease goes on, the longer we will feel our social existence continue to slip away from us.

Jake Scott is a doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham, specializing in political theory and populism. He is editor of the online publication The Mallard.