“They persuaded 138 Republican members of Congress to vote against the certification of Pennsylvania’s electoral votes, the most significant demonstration of no confidence in American democracy since the secession of the Confederate states.”

Voltaire warned readers of his 1765 work Questions on Miracles: “Anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit atrocities.” On January 6th, as an angry mob stormed the United States Capitol to prevent the results of the presidential election from being certified, the iconoclastic French philosopher was looking remarkably prescient. The assault on Congress was shocking, but it was not a bolt of lightning from a clear blue sky. In this article, I will argue that it was the result of the convergence of two long-running trends: declining confidence in the integrity of political systems and a deepening skepticism of authoritative sources of information. We can see these developing across the West; however, for reasons I will go into, both trends are further along in the United States.

Declining Confidence in American Democracy

For American elections to be contentious is nothing new. To begin with, the stakes in American presidential elections are sky-high. The President of the United States is the most powerful and influential person in the world and is extremely difficult to remove once in office. In the parliamentary system used in most of Europe, the Commonwealth, and Japan, a government can be removed or forced to submit to another election by a no-confidence vote, and close elections often lead to coalitions or power-sharing arrangements. In contrast, an American president who wins by a single vote is just as secure as one who wins in a landslide (France also has a presidential system, but the President must share power with a cabinet that answers to the National Assembly. Furthermore, the President is elected by national popular vote, and none of the Fifth Republic’s presidential elections have been particularly close). If a Dane finds himself saddled with a Prime Minister he despises, he can take comfort knowing that the Prime Minister is not his head of state (that would be Queen Margrethe II). A Prime Minister there might fall from power at any time and would not be able to trash the world in the meantime. Not so for the President of the United States.

The United States is also unique among Western democracies in having a patchwork of state and local elected officials conduct its elections rather than a national, non-partisan electoral commission. The American electoral system is an orchestra without a conductor, and it reflects the American preference for decentralization over centralization and election over appointment. The United States is also unique in its partly-elected judiciary, which strikes non-Americans as bizarre. This fact has almost certainly fed into the culture of litigating election results, which is also unusual by world standards. In the United Kingdom, for example, the major parties have long had a gentleman’s agreement against taking each other to court over election results.

All of this means that unusually close American presidential elections have been fraught with peril. The 1876 election, taking place with occupying federal troops still in the South, led to a constitutional crisis settled by an eventual compromise between the parties. In 1960, John F. Kennedy won the White House with a bare 8,858 votes in Illinois and a larger but still modest 46,257 in Texas. Some Republicans claimed—and not without basis—that Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and Senator Kennedy’s running mate, Texas Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, had used their formidable political machines to steal the two states. The defeated former Vice President, Richard M. Nixon, however, accepted Senator Kennedy’s victory and conceded. In the 2000 election, the system was pushed to the breaking point by an unbelievably close and bitterly-contested result in Florida. When the dust settled in court on December 12th, Texas Governor George W. Bush won the state by 537 votes out of 5,825,043 cast. Vice President Al Gore, who had conceded to Governor Bush and withdrawn his concession, conceded again. But with the margin that narrow, there would have been a question mark over the outcome no matter whose hand was on the Bible on January 20th.

President Bush won re-election in 2004 by nearly 120,000 votes in Ohio, a margin that would have been comfortable in elections past. However, some progressive commentators insisted that President Bush had stolen the election (again). In fairness to them, the election in the Buckeye state had not been handled with quite the professionalism it should have been. The CEO of voting machine company Diebold had declared that he was “committed” to delivering Ohio’s electoral votes to the President, and Ohio Secretary of State Kenneth Blackwell was a co-chair of President Bush’s re-election campaign. Democrats challenged the certification of President Bush’s electoral college victory in Congress and lost 267-31 in the House and 74-1 in the Senate, the first significant challenge to the result of a presidential election in Congress since 1877 (one faithless elector was challenged in 1969, but this would not have changed the result). The idea that the Republican Party had a well-oiled election-stealing machine was harder to defend following the party’s consecutive thumpings in 2006 and 2008, but the whole electoral edifice was still a little shaky as 2016 rolled around.

The Rise of Extreme Skepticism

Cognitive bias is universal, and one of its symptoms is unreasonable credibility towards people, sources, and ideas that fit in with a pre-existing worldview and excessive skepticism towards those that challenge said worldview and make one uncomfortable in the process. Historically, it could be tempered by those around us. Before the Internet, one needed to mix with neighbors, read the same newspapers as everyone in town, and watch one of a handful of television stations. Democrats, Republicans, and Libertarians all heard Walter Cronkite’s “and that’s the way it is” evening after evening. When one’s mad uncle began spouting conspiracy theories at Thanksgiving, he was met with a wall of stony faces.

For its adherents, the natural conservative distrust of complex solutions imposed top-down by experts became a distrust of anything experts said at all.

The Internet has given us access to more information and more like-minded people than ever before; this platform is one example. But it also allows us to isolate ourselves in narrow echo chambers. Said mad uncle can go online and find a hundred others who see the world in the same way. When one chooses his own news, he gets to choose his own facts. And under Cass Sunstein’s law of group polarization, an ideological group can collectively drift to a position that is more extreme than any individual member started out with.

These ailments afflict all ideologies, but we have seen—over the past 20 or so years—the rise of a particular pathology on the American right. For its adherents, the natural conservative distrust of complex solutions imposed top-down by experts became a distrust of anything experts said at all.

If I had to start somewhere, I would begin with young-earth creationism. According to a 2018 Pew poll, between 18-31% of American adults believe the world was created by God as it is now during historical times, and this belief is particularly common among evangelical Christians. White evangelicals are a key conservative and Republican Party constituency. Believing that the Earth is a few thousand years old might seem like a harmless eccentricity, but it also means believing that the world’s scientific community must either be unfathomably incompetent or engaged in a wide-reaching conspiracy to suppress the truth. Then, we get climate change, which is a more complex issue but shows a similar divide. In 2019, around half of conservative Republicans believed that climate change was driven by natural causes rather than human activity. Of course, the scientific community can—and has—been wrong many times in the past; however, its critics have often turned to sources of information that are far less likely to be correct.

The Trump Convergence

These two trends—declining faith in democracy and a growing skepticism about mainstream sources of information—finally came together in the person of the 45th President of the United States. Donald Trump launched his political career promoting the baseless conspiracy theory that President Barack Obama was not actually born in Honolulu, Hawaii, where his parents and grandparents lived and where his birth had been recorded in state records and announced in The Honolulu Advertiser. Speaking before the Conservative Political Action Conference in 2011, he claimed that “our current president came out of nowhere,” and “the people that went to school with him—they never saw him. They don’t know who he is. It’s crazy.” It was an easy claim to disprove. President Obama’s early life is well-known, and many have spoken of their personal experience with the young future president to the media. But Mr. Trump was undeterred. The social justice movement has been fairly criticized for making unfalsifiable arguments, but, in recent years, some of its critics have had the opposite problem: making arguments that are all too easily falsified.

But it continued the pattern where hardliners in the defeated party kept insisting that they had not really lost the election.

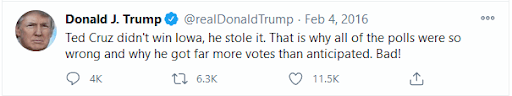

Calling the result of the 2012 election “a travesty” and a “great and disgusting injustice,” Mr. Trump entered the 2016 primaries himself, losing his first contest in Iowa to Senator Ted Cruz. He took to Twitter to accuse Senator Cruz of stealing the caucus through fraud. This claim was also baseless, and Senator Cruz (ironically given his enthusiastic support of the former President’s 2020 election challenge) brushed off the tweetstorm as another “Trumpertantrum.” However, it established a pattern where candidate Trump would allege that elections that he lost were fraudulent and, unusually for a politician, elections that he won, as well.

On the flip side, some on the Left argued that Russian interference made the 2016 election illegitimate. We know the Mueller Report established that the Kremlin did interfere in the election, but the impact of its interference is unknowable. Personally, I seriously doubt that a social media campaign could account for President Trump’s winning margin of 44,292 votes in Pennsylvania, 22,748 in Wisconsin, or 10,704 in Michigan. Amid protests, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton conceded defeat, and President Obama recognized President-elect Trump as his legitimate successor. When the electoral votes came before Congress, some left-wing members of the House of Representatives challenged the votes in a suite of states based on alleged Russian interference or perceived deficiencies in how the election was managed, but none gained the support of a senator. As such, none went to a vote, and all were brushed aside by Vice President Joe Biden. However, some Democrats, former President Jimmy Carter among them, maintained that President Trump was an illegitimate President. As Cathy Young has pointed out at Arc Digital, these allegations were never as far-reaching or widely-accepted as Republican claims of fraud in 2020, and there was never real doubt in the Democratic Party that President Trump and Secretary Clinton actually received the votes they were formally credited with. But it continued the pattern where hardliners in the defeated party kept insisting that they had not really lost the election.

The Boilover Year

The year 2020 would have been tumultuous even without the COVID-19 pandemic. In September, President Trump refused to commit to a peaceful transfer of power if he lost unless he could be satisfied that the election result was fair. So when President Trump took to the podium in the early hours of Wednesday, November 4th, to claim that he had won the election even as the count turned against him, the entire spectacle had an air of inevitability about it.

While politicians have cast aspersions at elections before, the claims made by President Trump and his supporters went before anything ever seen in the United States. President Trump claimed that systemic fraud had robbed him of a landslide victory, enough to overcome Vice President Biden’s more than 80,000 vote margin in Pennsylvania and tens of thousands more votes in other key states. President Trump and his supporters could not explain why Republican election officials in Georgia and Arizona would have co-operated with the scheme, why a Democratic Governor and Secretary of State in North Carolina apparently did not, why the Democrats did not perform better in Congress, or why the allegedly inexplicable swings towards Vice President Biden in urban counties in Georgia and Arizona were nearly identical to the swings in demographically similar urban counties in Texas. They could not explain why they were happy to seat Republican legislators elected on the ballots they insisted were fraudulent. They could not explain how this massive operation that must have involved thousands of people was planned, organized, communicated, and kept quiet. They could not explain how they would have expected a legitimate election to have played out, given it was blindingly obvious to election analysts that there would be a “red mirage” followed by a “blue shift” in states that counted in-person votes before mail-in votes.

The claims spread through alternative media, constantly shape-shifting, making them almost impossible to pin down and deal with. The fact that these arguments were rejected by Republican state electoral officials, media fact-checkers, 61 state and federal courts, or President Trump’s own Justice Department only gave them more credence among those who distrusted the institutions of the deep state. Efforts by both mainstream and social media to scrub these claims from the Internet seemed to vindicate them. Tellingly, the Trump campaign did not repeat these claims in its torrent of lawsuits, knowing that making baseless allegations in court is illegal. In one Pennsylvania submission, the campaign’s lawyers made it clear to the court that they “do not allege, and there is no evidence of, any fraud in connection with the challenged ballots.” Like Norman barons, they argued from motte-and-bailey castles. They persuaded 138 Republican members of Congress to vote against the certification of Pennsylvania’s electoral votes, the most significant demonstration of no confidence in American democracy since the secession of the Confederate states.

The Future

In politics, the English-speaking world is an American colony, and #MAGA has a surprising number of non-American devotees. I cannot escape it even here in Melbourne, Australia, and one of my own legislative councillors has taken to promoting on social media the idea that the 2020 election was stolen from President Trump. We may be approaching a fatal convergence in other countries, even the most historically stable ones.

The United States is now fragile. A majority of Republican voters do not believe the 2020 election was free and fair, particularly those who trusted the Trump campaign more than the media. The United States certainly needs electoral reform; however, no amount of reform will help if a sizable group of voters will simply dismiss—as an agent of the deep state—any electoral commissioner who certifies a result they do not favor. If Republicans win seats in 2022, which would be a normal result for a midterm election year, then theories of stolen elections might lose steam, as they did in the Democratic Party a decade-and-a-half ago. But those theories on the other side of the aisle were nowhere near as well-entrenched, nor were they as enmeshed in a completely alternative reality. Those living in Georgia’s 14th congressional district are now represented by a QAnon conspiracy theorist who has claimed that a deadly 2018 wildfire in California was started by the Rothschilds with a space laser. This is not a satisfactory state of affairs. And it is not impossible for today’s Republican Party to go backward at the midterms, particularly if it is cloven by infighting. Nobody knows what the endgame is. The worst-case scenario is that Western voters trash their democracies in order to save them from non-existent threats. But they may self-correct, as they have done in the past—if enough of us can think a little more like Voltaire.

Adam Wakeling is an Australian lawyer and writer. He has previously contributed to publications such as Quillette and Arc Digital.