“Having engaged with Schlesinger’s thinking, readers should ask themselves: Here in the 21st century, what are the greatest threats to the liberal democratic project at home and abroad?”

At times like the present, when politics is exceedingly partisan and personal, reminding ourselves of the greatness of the American experiment—of liberal democratic capitalism, written constitutionalism, majority rule, cultural pluralism, and safeguards for individual rights—is essential. Our political bouts have turned inwards, mercilessly focused on litigating past and present points of mutual grievance, and they have grown increasingly tribal, allergic to nuanced thinking and coalition-building around discrete issues of common concern. As we perform outrage vis-à-vis each other and denigrate the value of the society, economy, history, and government that shapes the contours of American life, we fail to appreciate the sanctity of the polity—and the past sacrifices, political theory, and insights into human nature undergirding it—that has been bequeathed to us. We lose sight of the awesome value of the republic we have been tasked with keeping.

That our internal squabbles have become so all-consuming while ideological foes like China grow more powerful and confident is somewhat surprising, as external threats tend to push us to look beyond domestic disputes. When an external “other” menaces the very existence of “us,” our enthusiasm for demonizing our fellow in-group members should wane. In light of the threat they pose, external dangers have a way of clarifying who we are and what we hold most dear as a nation. The Cold War was one such period in our national life that opened up pathways for heightened clarification, self-definition, and valuation. Many Americans failed to take advantage of such opportunities, opting instead to throw in their lot with demagogues like Senator Joseph McCarthy and to denigrate the liberal democratic values which communism threatened (and which they themselves purported to uphold) in the process. But others, like Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., allowed the Cold War and the communist menace to sharpen and illuminate their thinking regarding the nature of the American experiment, its value, and how best to preserve it.

In his 1949 book, The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom, Schlesinger mounts a defense of liberal democracy (the vital center) in the face of the right-wing and left-wing political extremes of fascism and communism. Written in the aftermath of Nazism’s demise and in the early years of Cold War competition between the U.S. and USSR, The Vital Center used the real-world prevalence of totalitarian political ideologies like fascism and communism to remind its American readers of the immense value of their experiment in liberal democratic self-governance. In doing so, Schlesinger offers sharp insights into human nature and government.

While geopolitical realities have certainly shifted in the intervening decades following the publication of The Vital Center, the book’s full-throated defense of liberal democracy is still very much worth revisiting and celebrating, especially in the midst of our global democratic recession and our weakening faith in democratic norms and processes here at home. Having engaged with Schlesinger’s thinking, readers should ask themselves: Here in the 21st century, what are the greatest threats to the liberal democratic project at home and abroad? The answers might prove uncomfortable.

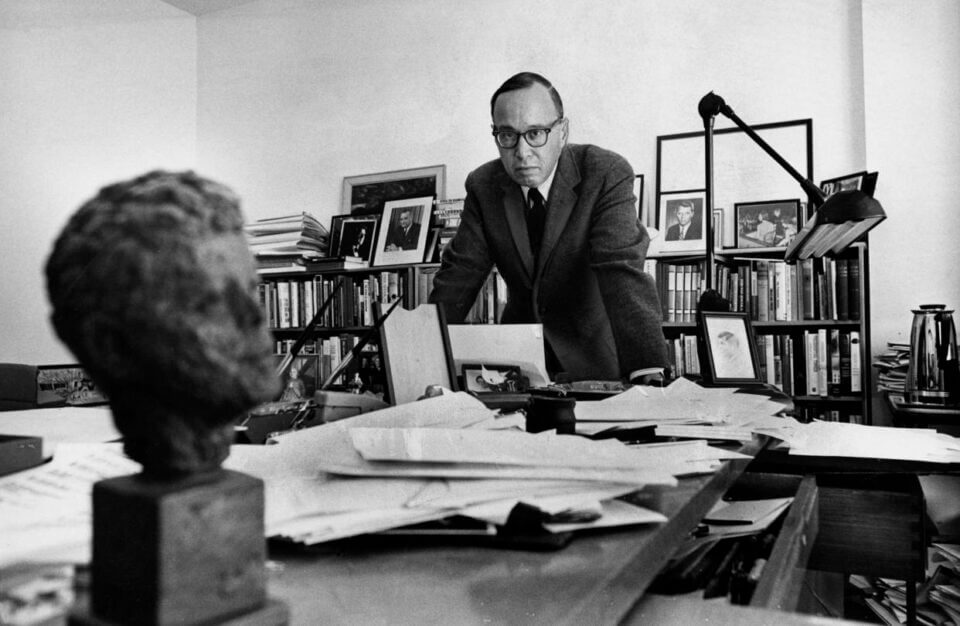

A Harvard historian who would go on to serve as a special assistant to President John F. Kennedy, Schlesinger pinpointed the source of the burgeoning ideological competition between the liberal democratic center and its extremist opponents: Industrialization. For Schlesinger, the rapid velocity of mass-scale industrialization had displaced the staid economic relations and cultural assumptions that structured society and helped give meaning to individuals’ lives in preceding decades. Industrialization impersonalized economic relations, isolating individuals and weakening the associational ties of civil society. With man sufficiently isolated, totalitarianism has a chance to take root. Schlesinger writes: “Against the loneliness and rootlessness of man in free society, [the totalitarian state] promises the security and comradeship of a crusading unity, propelled by a deep and driving faith.” As such, “The fear of isolation, the flight from anxiety lie at the bottom of the totalitarian appeal.”

On the one hand, liberal democracy is at a bit of a loss, as it cannot promise utopic visions that loosen humankind from the anxieties of modern freedom.

By premising totalitarianism’s appeal on the industrialization-inspired anxiety and anomie that can plague a free society, Schlesinger links both fascism and communism as two sides of the same totalitarian coin and charts a path forward for the preservation of liberal democracy.

Both communism and fascism, notes Schlesinger, fill “empty lives.” Totalitarian political ideologies promise the individual release from the strictures, anxieties, and complexities that plague his or her individuality by forsaking said individuality. By prostrating oneself at the altar of the one-party state that promises heaven on earth and liberation from some bogeyman of oppression, by engaging in the “escape from freedom,” the individual can extricate himself or herself from the burdens of freedom in modern society. Schlesinger argues: “Man longs to escape the pressures beating down on his frail individuality; and, more and more, the surest means of escape seems to be to surrender that individuality to some massive, external authority.” With their one-party states, secret police forces, suppression of dissent, and reliance on the sort of arbitrary violence that obliterates individuality (best embodied by the concentration camp), both communist and fascist states provide such authority. Communism and fascism, wrote Schlesinger, both fill a meaning-making void in modern life.

Having grouped communism and fascism under the same totalitarian umbrella, Schlesinger highlights the necessity of shoring up the strength of liberal democracy and outlines how to engage in that essential work. On the one hand, liberal democracy is at a bit of a loss, as it cannot promise utopic visions that loosen humankind from the anxieties of modern freedom. After all, “The honest defender of the free individual can only confess the uninspiring belief that most basic problems are insoluble.” Meanwhile, “The totalitarian promises a new heaven and a new earth.” Schlesinger is hyperaware of this disadvantage, writing: “Through this century, free society has been on the defensive, demoralized by the infection of anxiety, staggering under the body blows of fascism and Communism. Free society alienates the lonely and uprooted masses; while totalitarianism, building on their frustrations and cravings, provides a structure of belief, men to worship and men to hate and rites which guarantee salvation.”

However, even if the battle for free society can prove an uphill one in certain respects, it is a winning one so long as liberal democracies like the United States “supply outlets for the variegated emotions of man, and thus…restore meaning to democratic life.” In short, liberal democracies must busy themselves not only with providing economic prosperity, widespread subsistence, and the preservation of civil rights and liberties (all of which are tall tasks on their own terms); they must also make room for a robust civil society that is teeming with art, culture, voluntary associations, and great pursuits that dissuade citizens from turning to an all-powerful state to provide them with meaning. “We require individualism which does not wall man off from community,” writes Schlesinger, as well as “community which sustains but does not suffocate the individual.” How precisely to go about this project is, of course, a sticky question; however, the first step towards preserving liberal democracy is acknowledging the necessity of grappling with the question.

Here in the 21st century, our most prominent political leaders, at least, have yet to make that acknowledgment. We are far less clear-eyed than Cold Warriors like Schlesinger regarding the threats to liberal democracy and the inherent shakiness thereof. We seem content to denigrate and debase the liberal democratic project. In doing so, we open ourselves up to progressive (or, in Schlesinger’s phrasing, “doughface”) and populist escapes from reality and shield our eyes from the growing power and attractiveness of alternatives to liberal democracy, like the techno-authoritarianism of the People’s Republic of China.

If we are to shore up our faith in liberal democracy at home and push back more forcefully on its greatest foes abroad, we would do well to revisit books like The Vital Center, particularly their conception of human nature that lends itself to a defense of democratic self-government in the first place.

Schlesinger grounds his defense of liberal democracy in two fundamental truths: the inviolable dignity of the individual and the imperfect nature of humankind. When we actually recognize the inescapable realities of individuals’ inherent dignity and their woefully flawed nature, we will have taken an immense step towards appreciating the value of American democracy and its historic protections of decentralized rule and relatively free markets. The best that any society can do in the context of reality—in the face of human imperfection and complexity—is to uphold the inviolability of the individual, diversify power, and provide robust outlets for individuals to make meaning for themselves alongside one another.

The government itself, however, cannot provide that meaning. Whether they be promises of socialist utopia or calls of “I alone can fix it,” the progressive left and the populist right today fail to recognize this fact. Neither provides a functionable political program for revivifying faith in the American experiment—a faith that must be inculcated as the strength and sway of our most powerful ideological foes continually grows.

Thus, much as Schlesinger placed his faith in the non-Communist left and non-fascist right to uphold the vital center of liberal democracy in the face of its would-be totalitarian conquerors, the health of American democracy today—and its subsequent ability to stand tall in the face of its foremost anti-democratic competitors, China and Russia—hinges largely on the non-progressive left and non-populist right’s clear thinking and mutual cooperation. For those on both the Left and the Right who are tiring of the ascendant yet delusional left-wing and right-wing orthodoxies that neglect reality and downplay the virtues of American society and government, books like The Vital Center should serve as sources of instruction and inspiration. In the words of Schlesinger: “The center is vital; the center must hold.”.

Thomas Koenig is a recent graduate of Princeton University and will be attending Harvard Law School in the fall of 2021. He can be found on Twitter @TomsTakes98