“In one of the great exercises of academic sophistry in our times, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva wants to persuade us that color-blindness is racism, and color-consciousness is anti-racism.”

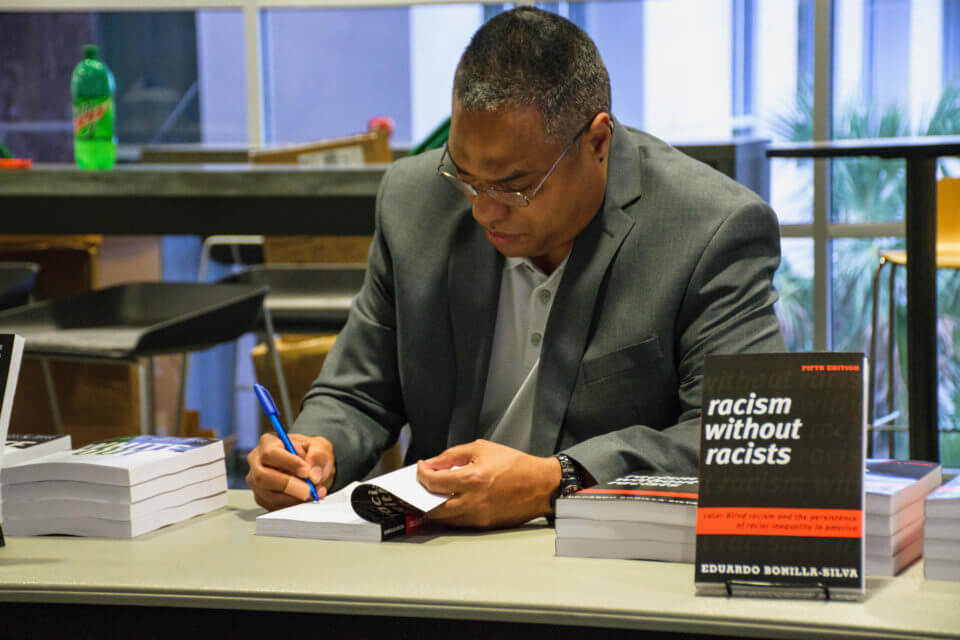

In the wake of George Floyd’s death, Robin DiAngelo’s widely-touted 2018 book White Fragility has become even more of a bestseller. Despite its popularity with many readers, the book has received many negative reviews. These negative reviews are mostly deserved, given that DiAngelo preposterously claims that if one denies being a racist, then that proves—all the more—that one is a racist. This argument—while outrageous—is far from new. Well before White Fragility, one prominent sociologist at Duke University, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, was making a similar claim. And, indeed, DiAngelo is sure to reference Bonilla-Silva several times in White Fragility. In Bonilla-Silva’s account, if one does not care much about race as a concept (a commonsensical definition of anti-racism), that proves one is a racist.

Martin Luther King Jr. famously dreamed of a day when his four little children “…will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” These are beautiful words. Yet, in our times, the phrase “I don’t see color” is considered a microaggression. How did we get to this confusing state of affairs? Bonilla-Silva’s influence has something to do with it.

Bonilla-Silva came up with the concept of “color-blind racism.” In Bonilla-Silva’s account, hardcore racism—as exemplified by hate groups, discriminatory laws, explicit attitudes and so on—is in decline. However, he argues that racism is as strong as ever. This is because, now, instead of expressing explicit hatred towards ethnic minorities, whites simply claim to not care about race, and, by doing that, they show themselves to be indifferent to the racial inequalities that persist. Therefore, they follow an “ostrich approach to racial matters.”

Bonilla-Silva presumably refers to the trope of the ostrich refusing to see reality by hiding its head under the sand. Yet, an alternative trope made famous by the psychologist Abraham Maslow could be used to describe Bonilla-Silva’s work and his concept of color-blind racism: When someone only has a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Bonilla-Silva, in his zeal for anti-racism, sees the entire world through the lens of racial discrimination, even when to do so requires greatly stretching the imagination. By his own admission, “detection of racial discrimination is extremely difficult for the party being discriminated against.” However, this admission does give him pause when he insists that racial discrimination is rampant. He is not concerned that there may be little objective evidence for his claim. This is because—in his view—sociology has made a pact with the “devil of objectivity,” and this is something that ought to be changed. It comes as no surprise that—in the new “woke” ideology—objectivity is a form of white supremacy.

Apparently, as per Bonilla-Silva’s interpretation, if someone simply feels discriminated against (and regardless of the objective evidence), that is reliable enough. Bonilla-Silva prefers subjective intuition over objective evidence, yet, by advocating for this, he fails to notice how perceived discrimination is not necessarily real discrimination.

This view leads Bonilla-Silva to some quite paranoid ideas. If someone greets him in a store and asks “May I help you?” Bonilla-Silva assumes this is color-blind racism and “smiling discrimination.” Ultimately, Bonilla-Silva’s view amounts to a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation. The civil rights activist Jesse Jackson has famously denounced that black clients are allegedly not duly taken care of in restaurants and stores. So, the implication is that—if one does not smile at these customers and greet them at the store—then he is a racist. However, then, as per Bonilla-Silva’s claim, if one does smile and greet them, he is also a racist.

Very much as Robin DiAngelo, Bonilla-Silva has decided that a particular thesis is true, and then he sees all evidence as confirmation of his thesis. He believes that in the United States (as well as in basically all white-majority countries in the world), so-called “systemic racism” is the order of the day. By this, he means that the whole system is racist and, therefore, everything within the country is permeated with racism. One can begin to see where Robin DiAngelo received inspiration for her preposterous claims. This is a classic example of confirmation bias, the same type of bias that characterizes those conspiracy theorists who argue that debunkers of conspiracy theories are part of the conspiracy itself. Bonilla-Silva’s theories are not falsifiable (in the Popperian sense); but, then again, he insists that sound methodological principles in science are—themselves—tools of white supremacy.

Bonilla-Silva’s main reason to believe that—even without any detectable form of racism, the system is still racist—is that racial inequalities are unquestionably present in countries such as the United States. The problem with this argument is that Bonilla-Silva gratuitously assumes that racial inequalities are due to racism, when, in fact, many other explanations are possible. This is correctly referred to as the “disparity fallacy” by Coleman Hughes, who defines it as follows: “the disparity fallacy holds that unequal outcomes between two groups must be caused primarily by discrimination, whether overt or systemic.”

In discussions over the last three decades, white supremacists have been fond of arguing that black people in the United States and other countries underperform for genetic reasons. But one need not embrace a racist (in the biological sense) view to explain why particular ethnic groups have different outcomes.

Culture may play a significant role in this disparity. Indeed, at least in the United States, the comparison of black immigrants (whether Caribbean or African) with African Americans is informative. Racially, the groups are the same, which means that both groups are similarly exposed to the same discrimination. Yet, black immigrants have better outcomes than African Americans. Discrimination—or, for that matter, natural intelligence—is clearly not sufficient to explain this difference. It seems more likely that the cultural values of black immigrants are more suited for success than the values that are more prevalent among African Americans.

From the outset, Bonilla-Silva refuses to acknowledge any role that culture plays in disparities between ethnic groups. And, according to Bonilla-Silva, whoever dares to bring up cultural variables in this discussion, is a “cultural racist.” In his words, “the cultural racism frame relies on arguments based on culture to explain the position of racial groups in society. In essence, whites ‘blame the victim’ by suggesting that the position of minorities is due to their family disorganization, lack of effort, or laziness.”

Bonilla-Silva’s work relies on multiple interviews with non-academic white subjects who express these views—but in rather clumsy and vulgar terms. These comments make an easy target for Bonilla-Silva’s label of “color-blind racism.” Yet, Bonilla-Silva fails to engage with more sophisticated scholars who have extensively documented cultural shortcomings of African Americans in the United States and how this might partly account for differences in outcome.

The rude stereotype of the African American “lazy” person surely has a long, vicious history, and Bonilla-Silva’s white interviewees presumably echo it. However, Bonilla-Silva paints cultural critiques with too broad of a brush. Ever since Max Weber’s 1905 work The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, there is a strong sociological tradition of comparing work ethics across different ethnic groups. If a study offers data that suggests that the African American work ethic is weaker (such as this one), then the reasonable response is to either accept it or to critique its methodology. However, it simply will not do to dismiss it by assuming that any cultural comparison is fundamentally racist.

As opposed to laziness, family disorganization in the African American community is not a rude stereotype. This characterization has a strong basis in reality. In 1965, the Moynihan Report already warned about this; and, ever since, it seems the situation has not improved: In 2017, 77.3 % of non-immigrant black births in the United States were illegitimate, as compared to 25% in 1960.

By insisting that bringing up such statistics is a form of “cultural racism,” Bonilla-Silva dismisses the importance of family organization in explaining disparities. But, these are not trivial variables; family disorganization has a significant impact on criminality. In an important study on male delinquency, William S. Comanor and Llad Phillips conclude that “the single most important factor affecting these measures of delinquency is the presence of his father in the home.” It is not hard to see the chain of reasoning here: Greater levels of family disorganization in the African American community lead to higher crime rate, which, in turn, decreases positive outcome on other metrics. Culture matters, and disparities cannot be entirely blamed on discrimination.

Bonilla-Silva falls into the same trap that, unfortunately, many anti-racists have fallen into: cultural relativism. He assumes that—inasmuch as it is extremely difficult to argue that one race is superior to another—this also holds for cultures. Given that he refuses to believe that not all cultures are equal, Bonilla-Silva concludes that if there are racial inequities, these must be solely due to discrimination (because all cultures have the same worth). Yet again, this is the disparity fallacy.

However, in the United States and other countries with a history of racial conflict, racism has, at times, been overused as an excuse for failure—or has been illegitimately brought as an argument into matters that have little to do with it.

It is, of course, true that racism still exists in the United States and in other places—and even in some of the insidious manners that Bonilla-Silva describes. His work, however, relies mostly on mere anecdotic evidence of white people claiming to be color-blind yet not having black friends and not fully approving of interracial marriage. (Let us recall that, for Bonilla-Silva, hard evidence that goes beyond the anecdotal is not necessary because sociology must get away from the “devil of objectivity.”) Yet, he does cite more robust studies of racist practices, such as real estate agents declining to rent apartments to a black subject.

However, in the United States and other countries with a history of racial conflict, racism has, at times, been overused as an excuse for failure—or has been illegitimately brought as an argument into matters that have little to do with it. Again, in his studies, Bonilla-Silva aims for the easy target of unsophisticated white subjects who, though claiming not to be racist, accuse black Americans of “playing the race card.”

Predictably, Bonilla-Silva accuses these people of being color-blind racists. Yet, he refuses to acknowledge that there is such a thing as playing the race card. And, once again, he refuses to engage with more sophisticated authors who—without the emotional overload of a non-academic white subject—do carefully document and analyze how the race card is played in many aspects of life. Consider, for example, Richard Thompson Ford’s 2008 book The Race Card: How Buffing About Bias Makes Race Relations Worse; in this particular piece of scholarship, Ford carefully analyzes how irrelevant racial arguments are frequently brought up in scenarios where they ought not be, from Hurricane Katrina to professors waiting for taxis.

But, perhaps the danger of Bonilla-Silva’s views—and his concept of color-blind racism—is not so much his eagerness to see racism everywhere but, rather, his proposed concrete alternatives for societies such as the United States. By disparaging a color-blind approach to racial relations, Bonilla-Silva proposes a color-conscious approach in which race is very relevant—and in which the enhancement of ethnic identities is encouraged. In his view, the State should nurture awareness of ethnic differences so as to fight racism. In other words, Bonilla-Silva encourages playing the identity politics game.

One may sympathize with his anti-racist intentions, but he fails to notice that he shares with old-fashioned racists (hate groups, segregationists, and so on) this fixation on race. Bonilla-Silva pays lip service to integration, but he insists that the way to reach real integration is by disregarding a color-blind approach. Again, it is difficult to understand how focusing overwhelmingly on racial differences and deriding the idea of coming together as a unified nation can possibly bring forth integration. Indeed, it is very telling that—according to Bonilla-Silva’s own confession on a podcast interview—he chooses to engage with whites only on workdays, from 9 am to 5 pm, “to keep sanity.” In his writings, the professor is a bit more careful and keeps his chauvinism to himself; however, in conversation, the pretense is over: He does not appear to care much for integration.

Bonilla-Silva is concerned that the United States is becoming “Latin Americanized.” In Latin American countries, governments have typically made sure that national identity is more important than ethnic identity; consequently, race, as a concept, is not as salient there as in the United States. In Bonilla-Silva’s view, this makes race relations worse—inasmuch as oppressed groups have no consciousness of their situation. The jury is still out on how bad race relations are in Latin America. Racial disparities in those countries certainly exist (but again, why assume ipso facto that disparities are evidence of racism?), but after the (mostly peaceful) abolition of slavery in those countries, there was nothing like Jim Crow, anti-miscegenation laws, or redlining. The level of racial confrontation that is frequently experienced in the United States is largely absent in Latin America. Racism surely exists in Latin America, probably in more subtle ways, but I am not at all persuaded by Bonilla-Silva when he claims that racism in Latin America is much worse than in the United States.

Be that as it may—even if Bonilla-Silva is correct to be concerned about the Latin Americanization of race relations in the United States—he fails to see that his emphasis on racial identity carries the far greater risk of “balkanizing” the United States—or, for that matter, any other country that excessively promotes identity politics. To this point, at the time of the wars that broke apart the former Yugoslavia, many scholars in the United States were concerned that the emphasis on ethnic identities could, very well, destroy their country too, leaving all ethnic groups with a far worse outcome. Most notably, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. criticized what he called the “cult of ethnicity.” As Schlesinger put it:

“In the 20th century, new immigration laws altered the composition of the American people, and a cult of ethnicity erupted both among non-Anglo whites and among nonwhite minorities. This had many healthy consequences…But, pressed too far, the cult of ethnicity has unhealthy consequences. It gives rise, for example, to the conception of the U.S. as a nation composed not of individuals making their own choices but of inviolable ethnic and racial groups.”

Racism can only persist when there is an excessive awareness that people vary in their physical traits. This excessive awareness is not truly natural to the human species. Racism has some very precise historical origins. Thus, in the same manner that there was a time when race was irrelevant, there may well be a future time when race again becomes irrelevant. Yet, instead of resisting racism, good-intentioned authors such as Bonilla-Silva are actually reinforcing it, by making people more aware of race than they otherwise would be.

The political ascendency of President Donald Trump may be proof of this argument. In the years prior to President Trump’s rise, identity politics (as encouraged by people such as Bonilla-Silva) was on the rise among minorities. It was only a matter of time until white Americans figured out that if other groups can be so conscious of their ethnic identity, why can’t white Americans be, too? In a recent piece for Spiked, Inaya Folarin Iman writes, “…in recent years we have witnessed the gradual erosion of universalist ideals, in favour of multiculturalism and race-based identity politics…Unfortunately, this development has consequently provided a new vehicle for far-right groups who seek to coalesce around and elevate whiteness as an identity. It provides a new social justification for racial thinking, which can gain traction by framing whiteness as an ‘oppressed’ identity that is being demonised and is under threat by an asymmetric status quo that favours ethnic minorities.”

Racism can only continue as long as people structure their social relations around the concept of race. In one of the great exercises of academic sophistry in our times, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva wants to persuade us that color-blindness is racism, and color-consciousness is anti-racism. In the same manner that Socrates confronted the sophists of his day by calling a spade a spade, we now face the task of returning to common-sense and coming to terms with the fact that the only way to overcome racism is by ceasing the obsession with the very concepts that give rise to it.

Dr. Gabriel Andrade is a university professor. His Twitter is @gandrade8o.

Yet, there is a culture of hard data and objective information, that has no evidence of being better. In the west we have histórical record of scientific racism and white supremacist with their biológical reductionism and scientism, making the race war worse.

I can desgarre with Bonilla without using an obssesive “see the logical fallacy” framework. It’s disgusting that thre is no way today for make a great joke or a wise comment without being virtue signalling by logical-Analytic morons. I know tha in my latín america country we have little problems with racism against black people, but situations against not capitalist people and natives. I don’t know if I can call those situations racism, but there is supremacy in the core. USA can be better with more latinos in this issue, actually.

Who was it who said that only an intellectual could believe such absurd ideas?