“This explains the turn to nostalgic and resentment-driven politics to seek to elevate authority figures who will not only halt the flow of time but turn back the clock.”

Introduction

Ever since Francis Fukuyama’s seminal end of history thesis, there has been much deliberation about how we understand the relationship among time, meaning, and freedom. These are obviously large questions, and—in this short essay—I hope to provide a brief genealogy of some transitions in how we have come to conceptualize these ideas in Western societies. This essay will primarily draw on the work of Georg Hegel, who was undeniably the philosopher who took these questions most seriously—for better or worse. I also think that understanding how we conceptualize time, freedom, and meaning in what we now call post-modernity can tell us a great deal about contemporary attitudes and politics. In particular, this sheds light on why reactionary movements like post-modern conservatism (see my new book here) have gained much appeal in the early days of the 21st century.

Time and Freedom in the Classical and Christian Periods

“Lastly, why would He make any thing at all of it, and not rather by the same All-mightiness cause it not to be at all? Or, could it then be against His will? Or if it were from eternity, why suffered He it so to be for infinite spaces of times past, and was pleased so long after to make something out of it? Or if He were suddenly pleased now to effect somewhat, this rather should the All-mighty have effected, that this evil matter should not be, and He alone be, the whole, true, sovereign, and infinite Good. Or if it was not good that He who was good should not also frame and create something that were good, then, that evil matter being taken away and brought to nothing, He might form good matter, whereof to create all things. For He should not be All-mighty, if He might not create something good without the aid of that matter which Himself had not created. These thoughts I revolved in my miserable heart, overcharged with most gnawing cares, lest I should die ere I had found the truth; yet was the faith of Thy Christ, our Lord and Saviour, professed in the Church Catholic, firmly fixed in my heart, in many points, indeed, as yet unformed, and fluctuating from the rule of doctrine; yet did not my mind utterly leave it, but rather daily took in more and more of it.”

St. Augustine, Confessions

Hegel made the deep observation that there are many ways to approach the subject of time. Time is obviously a concern for physicists and mathematicians, who both tend to puzzle over its physical characteristics. But it is also a concern for all living beings as the experience their life individually and communally. This makes it crucial to interrogate not just the physical concept of time—but how it temporality presents itself culturally. Hegel argues that for the Ancient Greeks, time had an ultimately unreal quality. For Plato—and to a lesser extent Aristotle—this world of time was little more than an approximation or shadow of the true eternal world, which existed in the beyond. For human beings, time was the realm of fate and fortune but never of freedom. We were driven by forces beyond our control to play out inevitably tragic tales. This was true both for individuals and civilizations. Consider the famous play Oedipus Rex where the titular character was fated to slay his father and marry his mother. Despite desperate efforts to prevent such horror, the clever and brave Oedipus, nevertheless, cannot escape his fate. After inheriting his father’s kingdom, its slow decline forces him to realize the truth, and Oedipus then blinds himself to see no more. There was no escaping such fate, which is why the world of time was not one of freedom but nihilistic tragedy—full of sound and fury but signifying nothing, in Macbeth’s famous words. The only way to overcome this problem was to direct oneself to the eternal and perfect world beyond this one, which occasionally intervened in the world of time through miracles and favoritism to temporality protect its favored beings. Hegel observed that—at the time—there was much to learn from such a fatalistic approach to time. But classicism now is invoked primarily for reactionary purposes—consider the popularity of right-wing narratives of decadent decline and fall ala Oswald Spengler through to Sohrab Ahmari. Such figures, despite their posturing to be saving Western civilization, actually want a regression to a pre-Christian concept of time as governed by fortune, strength, and will—for a while before the inevitable fall sets in.

Hegel then goes on to describe how conventional Christianity occupied a middle place between the fatalistic time consciousness of the Greeks and our modern progressive sensibility. For early Christians, God still existed in an eternal realm outside of time and intervened at various points to improve his creation. But God also felt such agapic love for his creation that he entered time as a human being, lived for a finite period, and died to redeem the world. As a consequence, the Holy Spirit descended, and the world of eternity became permanently available to everyone. However, this imposed an onus on each person to live up to the standards set by eternity within time: an aspiration open to all but reached by very few. This established the conditions for the truly modern emergence of freedom with Enlightenment.

Modern Concepts of Time and Freedom

As time went on, the mythological elements of Christian doctrine began to have less sway while its ethos deepened. With the advent of modernity, we became more skeptical that there was indeed a literal God existing in heaven surrounded by choirs of angels. However, Western civilization internalized the expectation that being moral must come from us. Starting in the 18th century, this blossomed into liberalism—and, in particular, Kantianism, the deepest articulation of liberal philosophy. Modern people no longer see morality as emerging from outside human beings; it was not externalized in any sense. Instead, morality and meaning had to come from within, via the free creation of what mattered to human beings. As Robert Brandom put it in his great new book A Spirit of Trust:

“Where for the Greeks the norms had been part of the natural world, for Faith they are part of the supernatural word. But that is a specific difference within a general agreement that norms are grounded in ontology and matters of fact, in something about how the world just is antecedently to its having human beings and their practical attitudes in it. Those norms and their bindingness are not understood ad products of human attitudes and activity, though they in fact are instituted by people acting according to the pure consciousness of faith. Believers institute these norms by their attitudes, but they do not understand themselves as doing that. Faith has not embraced the fundamental, defining insight of modernity: the attitude-dependence of normative statuses.”

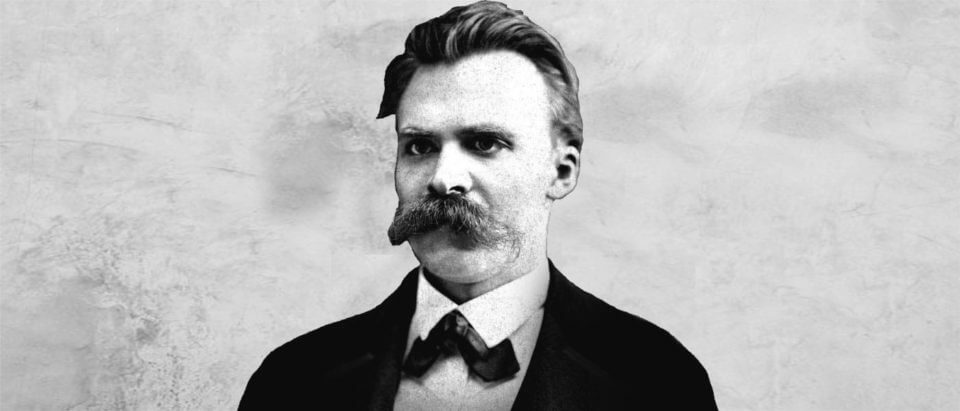

In other words, we were now free to create morality ourselves. For Hegel and other moderns, this was terrifically liberating. It also married onto a progressive vision of history as the gradual movement towards maturity and genuine freedom. From seeing morality as being imposed from the outside, moderns had finally accepted that they alone were responsible for determining what was of value—and for living up to their self-imposed principles. But very quickly the dark underside appeared. Nietzsche observed that the triumph of modernity had been to liberate human beings from the tyranny of externally-imposed morality, leaving us with absolute freedom. But this was also a terrible burden, since nothing could definitively answer many of the key existential questions we had. Freedom to do what? Freedom to be what? Our lost relationship to eternity also had tremendous consequences. Without eternity, all we had was the world of time. As such, we had to face up to the fact that everything was impermanent; even the most enduring human institutions and values amounted to little more than seconds in the cosmic story. Even life took on an unreal quality; since non-existence endured far longer than life, it was as though living were but a shadow cast on the wall before its fragile light was snuffed out by power. Under these conditions, Nietzsche said it would not be enlightened progressive moralists who assumed control, but the resentful. Feeling their powerlessness before endless and destructive time, moderns would pursue even monstrous acts in order to enjoy the sense of domination that came from it. This is where the reactionary temptation comes in, which provides a false solution to these challenges.

Conclusion: Post-Modern Conservatism and Time

Post-modern conservatives embody this Nietzschian spirit of resentment, though in a kind of debased manner. Unlike the great nihilists he predicted, post-modern conservatives are unable to accept a world governed by the endless flow of time and the corrosion of all human efforts. As reactionaries unable to accept such change, they cling to the past as a source of meaning. This reinscribes the unfreedom of earlier historical epochs and their conceptions of time into the present. For post-modern conservatives, the here and now (and the future) represent the possibility and freedom to change the world. But as far as they are concerned, change is the enemy to be confronted at all costs. This explains the turn to nostalgic and resentment-driven politics to seek to elevate authority figures who will not only halt the flow of time but turn back the clock. The impossibility of this was well-noted by Nietzsche, who in addition to being an anti-nationalist saw such nostalgic reactions as the most impotent form of nihilism. Reactionary nationalists and xenophobes were not just nihilists but weak and boring nihilists who could not even face nothingness head-on. They needed to turn to the past and sacral father figures to provide a sense of direction and meaning. We would be well-advised to consider his thoughtful criticisms today.

Matt McManus is Professor of Politics and International Relations at Tec de Monterrey, and the author of Making Human Dignity Central to International Human Rights Law and The Rise of Post-Modern Conservatism. His new projects include co-authoring a critical monograph on Jordan Peterson and a book on liberal rights for Palgrave MacMillan. Matt can be reached at mattmcmanus300@gmail.com or added on twitter vie @mattpolprof

About your conclusion.

Don’t post-modern liberals also embody that spirit of resentment? Unlike their conservative counterpart, they try to demean and destroy the past. Both seem dangerous to me. The past should be evaluated from more of a balanced point of view with things worth building upon and others needing refurbishing. I felt this article might steer a bit too much against the worth of the past.

Trumpism and Nietzschean resentment are integrally related. Your fine essay makes that point well. I would ground your abstractions like time, freedom, etc., in economic and sociocultural factors. Namely, Trumpism is a doctrine for those who lacked the cognitive skill sets to prosper in the Age of Globalization and the New Knowlege Economy. Trumpists are less educated than their more successful counterparts. So they resent bicoastal elites who managed to thrive in a changing interconnected world. A similar envy existed against Jews and urban professionals in the late 1920’s and 1930’s in Germany. A better essay would have grounded abstract concepts like time, meaning and freedom with social and racial resentment driving Trump worship among the rural, the White, the less educated and the religious. Regardless, thanks for

your great essay. (I apologize for not being able to edit my reply).

May I ask, do you see the resentment in your own argument? The essay, it should be said, fails to point out that Nietzsche writes of two different types of ressentment.

“Ressentiment itself, if it should appear in the noble man, consummates and exhausts itself in an immediate reaction, and therefore does not poison: on the other hand, it fails to appear at all on countless occasions on which it inevitably appears in the weak and impotent.”