“Like [how] the Southern District of New York became the hub for financial crimes, the Northern District of Georgia has become a hub for online financial crimes and cybersecurity because it all runs through our network.”

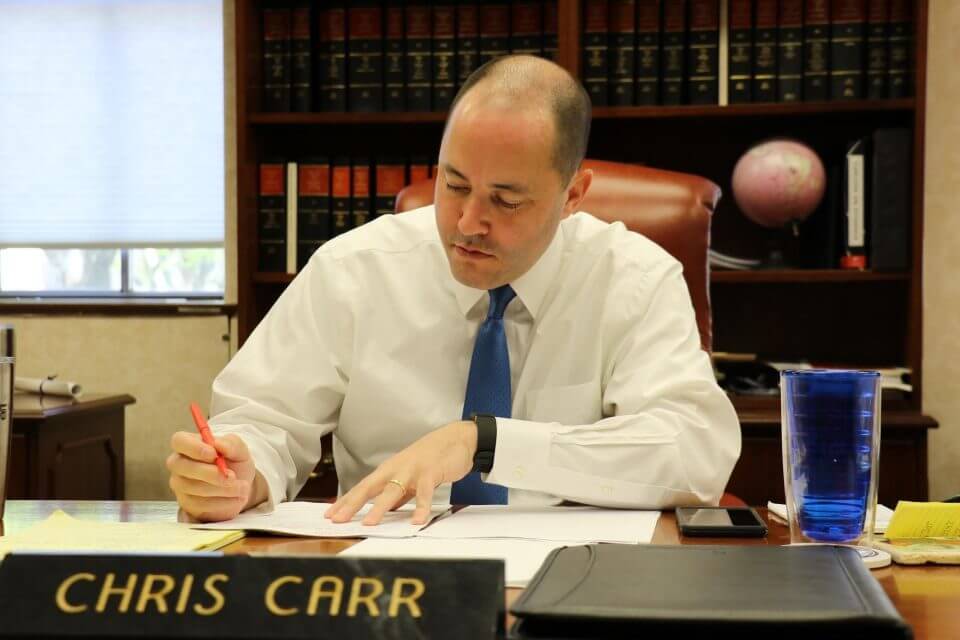

Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr has served in his current role since November of 2016. Mr. Carr had previously been chief of staff to United States Senator Johnny Isakson (R-Ga.). Since assuming the role of Attorney General, Mr. Carr has made addressing gang violence a priority, and, in concert with Governor Brian Kemp and First Lady Marty Kemp, he has been involved in an initiative to raise public awareness about human trafficking. Mr. Carr has also gained attention for appearing in a series of online videos with various athletes to discourage underage drinking. Merion West editor Erich Prince speaks with Attorney General Carr at the Attorney General’s office in Atlanta. The interview focuses on the Attorney General’s efforts to address gang violence in the state, reduce the prevalence of human trafficking, and ensure that cybercrime is properly prosecuted.

Starting off, I want to bring up the op-ed you you had with us in September. You talked about the extent of gang crime, the extent of gang violence, and I think a lot of people are a little surprised to hear how prevalent it is. I know in that op-ed you cited that, “nearly half of all violent crimes are gang-related.” Why are we not hearing more about this, and can you talk about the extent of the problem because a lot of people hearing this for the first time are fairly surprised about the extent of it.

Sure. And I think the reason that folks haven’t spoken more about it is—I think there was some sort of fear of talking about it. Or maybe there was some sort of embarrassment that this might be happening in our community, but what we’ve seen is that the gang issue and this crisis is not unique to Georgia. It’s not just an urban or suburban or rural issue; it impacts the entire state, as it does many other states. And so what I’ve seen is—and I’ve really seen it over the last twelve to eighteen months—I commend Governor Kemp; he has raised this issue. He ran on it when he ran in 2018. He has hired Vic Reynolds, an outstanding former prosecutor as head of the GBI; he has put resources toward it. But the media has also been paying attention to this issue. So I’ve really seen—in the last twelve to eighteen months—that there has been a greater awareness in the community at large—and I mean that statewide—to address this issue. And what I have found is [that] people have seen gang activity in their community. They just wanted to know the cavalry’s coming. What you’ve seen in Georgia is you’ve seen this emphasis on making sure we take care of violent criminals, get them off the streets, dismantle those who are trying to sell human beings, or guns, or drugs, or perpetrate cybercrimes, or steal benefits, or whatever it may be—and make sure that we do something about it.

And you think in the past—and maybe still ongoing—[that] there’s a disincentive for some elected officials, communities, or chambers of commerce to say, “We have this problem, let’s do something about it”—maybe it’s been easier to sweep it under the rug?

I think there’s been a concern about talking about it. And the way I’ve seen it—I’ve said this many times, as it relates to gangs, I think there’s two ways you can look at it. You can acknowledge there’s a problem and get everybody on board to solve it, or [you can] pretend you don’t have a problem, and it’s going to get worse. I think we’ve been very fortunate—at this point in time—[that] we have three U.S. attorneys that are outstanding [and] have focused their attention on the federal level. The FBI’s been great, so we’ve got federal partners. As I mentioned, the Governor, the GBI, corrections, juvenile justice, state-level folks. Our office has been focused on it; we created the Georgia Anti-Gang Network to get them into the room, and we have sheriffs that have been on the front lines, the police chiefs, and DA’s throughout the state. So for the first time, through our Georgia Anti-Gang Network, we got everybody in the room saying: “Alright, we need a network to fight this network,” as Bobby Christine, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District talks about—this is the network; let’s talk about how we can solve the problem and get results.

So one of the things I hear fairly frequently in the various op-eds we’ve had on the topic, and even this morning over at GBI—a lot of the folks there are supportive of this federal anti-gang law. Can you talk about how, at the federal level, that might make people’s jobs easier in the various states?

As a state AG, I’m a big believer in federalism, so we’ve obviously got a great gang statute in Georgia. And I honestly don’t know why a federal gang statute has not made it farther in Washington, but if you talk to law enforcement, they say it would be an outstanding arrow in the quiver to allow our federal partners to be able to go down that path. Why hasn’t it gone farther in Washington? I’m not sure, but I do know this: it works in Georgia. And our folks at law enforcement and the GBI will tell you [that] it’s an effective tool to make sure we protect communities that are vulnerable and are being taken advantage of. And I think you’ll see more awareness as we go down the road.

So as people try, across the country, to understand the gangs of today, I’ve heard a lot of comparisons to how they’re similar to and different from the Italian mafia, which people may be more familiar with. I’ve heard described to me that certain newer gangs are less focused on profit and minimizing violence and some are more focused on showing strength through violence—how do these gangs differ, and do they have this code of silence that’s strictly maintained? Do they have a strong hierarchy? And I know there’s a variety of different gangs: white gangs, Hispanic gangs, black gangs. The President talks a lot about MS-13, but that’s only one of them. Maybe it’s hard to make sweeping generalizations about all these new gangs, but how do you see it—for those more familiar with the Italian mafia, how does it compare and contrast?

I’m probably not the best historian on the mob, but Mike Carlson, who works for the GBI, would be a great person to talk to.

Yes, I was with him for a while this morning.

He can tell you about that. What I have seen, regarding the gangs we are dealing with now, is two-fold. One, it’s all about making money right now: selling guns, selling drugs, selling human beings. Like I mentioned before: benefits too. There’s even an element of elder abuse, as you go along, because any way you can make money, they’ll try to make money. Cybercrime—there’s a profit motive. But within that, there is a violent element to it. We know that eighty percent of all human trafficking is somehow gang-related. We know that over fifty percent of all violent crime is gang-related. But we also know that they are out there making money, and they will work with each other in order to do just that. I know that at this point in time, it’s about making money, and the violent element of it is something we have to be aware of and continue to focus on as we go down the road.

So human trafficking wise, I understand that’s been an initiative of the Kemp administration [and] your office. I understand the first lady, Marty Kemp, is very focused on this. When I landed at the Atlanta airport a day or two ago, it was the first thing I heard at the Atlanta airport, on the tram car, was to be on the lookout for human trafficking. What are some of the main efforts you’re doing—I understand there was House bill 732, including those who patronize these folks—what are some of the efforts you’re doing to counteract human trafficking?

The big thing that we’re excited about and that we’re focused on—and that I’m so grateful for the Governor and First Lady, the Lieutenant Governor and the Speaker and legislative leadership—was that the state of Georgia has had the ability to prosecute human trafficking since ’06, but we’ve never put the resources or personnel toward doing that. This past legislative session—with their support—we now have a human trafficking prosecutions unit that’s up and running as of July 1st. And we’ll be fully staffed by Labor Day. So we’re going to have two prosecutors and an investigator; we’re going to have an anti-crime analyst; we’re going to have a victims advocate—and we’ll be able to work with federal, state, and local partners to each and every day prosecute those who are buying and selling kids for sex and rescue the victims. So I’m thrilled about that. We have worked with the legislature for the past two or three years to make sure that soliciting for the purpose of human trafficking is a crime, patronizing is a crime; we worked on making sure that we now have legislation passed last session. One of the big initiatives is making sure we have victim-centered treatment. These are unique cases, as we talk about domestic minor sex trafficking; we’re talking about children. The average age of the victims is a 12-14 year old girl. It’s not just girls, boys as well. So you have a very unique, vulnerable population that we’re having to deal with.

And it’s also training. At the end of the day, we ask law enforcement to be all things to all people. The more we can train law enforcement to build cases, and that’s part of what our prosecution team wants to be able to work with local communities on that. We want to be able to train law enforcement but also the community at large. To be able to see something that’s a red flag.

That’s right, and I was browsing around your website, the Attorney General’s website; you talked about these human trafficking red flags and making people aware of what to look for and observing when something doesn’t seem right. Someone coming with new clothes, for example, and they’re not sure how they got them, and a younger person…

An older male, younger girl, not making eye contact, that sort of thing. And then getting over the stigma of saying, “I’m not going to call law enforcement. I’m sure it’s not anything wrong.”

So part of it is public information—I’m on the way to the airport, and I see something that isn’t right. I make a phone call to the local police and report this, and they can start to look into it. It’s about making the public aware of it as well, so they can be partners with law enforcement.

That’s it. And it’s a partnership. I think it’s a community partnership. As I’ve said, it would be better that somebody reports a situation and be wrong than to let one more child get abused. That’s what we’re looking at. There’s been retail partners, signs posted in restrooms in restaurants, hotels—the hotel industry’s been part of the training. Delta Airlines has trained all of their flight attendants. UPS: two great Georgia companies. Think about it—UPS is in every neighborhood in the world, training their drivers what to look for and that sort of thing. So there’s been great corporate buy-in, as well. Again, it’s like with gangs; you’re seeing the awareness raise dramatically. If you’re leveraging community support—if you’ve got federal, state, and local law enforcement on the same page and working on training or working on prosecuting—we’re going to have some good success.

I’ve read a fair amount on the human trafficking issue about the number of people who are trafficked for labor-related reasons. I know the sex crimes gets the bulk of attention—as maybe it well should—but globally there’s more people trafficked for forced labor than for sexual exploitation. How is it similar and different to look at these cases where people are being trafficked for labor (agricultural sectors and such) versus sex trafficking?

All of it can be wrong; all of it can be a living hell. Our office is focused on domestic minor sex trafficking. That’s just the area that we’ve decided to focus on. But human trafficking is human trafficking. I think Polaris, the national standard nonprofit, will tell you there’s 30-some different subsets of human trafficking. A lot of it, like you said, is forced labor versus sexual servitude. Our office is focused on sexual servitude. But I believe in the dignity of every human being, and if somebody is being forced into anything—whether it be sexual servitude or forced labor—that’s a violation of the law and we need to look into it. We just focus more on domestic minor sex trafficking. Not because the others don’t matter, that’s just been our focus.

And tying this back to gangs—so you’ve indicated that this is one of the ways gangs make money—do you have a sense of the degree to which gangs are responsible for this human trafficking? Are they providing a bulk of it, a large portion?

The study that we’ve seen, and Katie can get that to you, shows that 80% of all human trafficking is gang affiliated. What’s horrific about it is that gangs see these children as a reusable resource. And that just totally demeans children; it demeans humanity, and it demeans their dignity. But [the gangs will] move around; they’ll use the internet. They’ll say, “Hey, we’ll be in this town today, or that town tomorrow,” so they’ll take folks on the go and cross state lines. So you’re seeing state attorney generals, as a group, focused on human trafficking. So that’s because—like with gangs—human trafficking doesn’t stop at the county line or the city line. It’s a statewide issue. It’s a national issue. And so you’re seeing us work together, and hopefully we’ll be doing more of that as we go down the road.

What are some of the challenges in prosecuting this sex trafficking that make it particularly difficult? I was reading Bill Barr at the beginning of the month was describing some of the difficulties and Hillary Axam, who was a top prosecutor for the human trafficking unit, said that sometimes it can be difficult to prove that the victim was indeed being trafficked against the victim’s will because it requires getting to the victim’s mind. John Melvin [Chief of Staff at the GBI] this morning was saying that you can take into account the various factors—coming into hotel rooms, see certain things going on—[but that] there are certain challenges that make prosecuting human trafficking more difficult.

There are, and you might want to talk to Hannah, who’s our lead prosecutor. One of the challenges—when you’re talking about domestic minor sex trafficking—is the age of the victims. And the experiences that they’ve been through and getting them to testify against those that have taken advantage of them. One of the things that Hannah talks about is once you start peeling back the onion—you see that it’s generally not just a one-off case. You start seeing a network. And to have the resources to be able to prosecute those cases—is where our office will be able to play a key role across jurisdictional lines.

Katie Byrd [Attorney General Carr’s Director of Communications]: And that’s why we have a victim advocate as part of the human trafficking prosecution unit.

Attorney General Carr: Which is why it’s key. And why that was a key focus—when we talked about the six [positions that our office would staff]; you had to have a victim’s advocate because of the trauma that these individuals have been through.

That’s a sentiment I’ve heard expressed—I understand recently there was a sting in Georgia about people who were engaging in sex abuse of minors via the internet, and that it frequently hadn’t been the first time. This was something they did on a regular basis.

That’s my understanding as well; that it’s generally not the first time.

And how do you see—looking at human trafficking crimes, as relating to the cyber investigations that I’ve been hearing about going on in the state, and looking into cyber crime, is it a multi-pronged approach?

It is. And another thing—we’ve got a great head of our GBI in Vic Reynolds and all that they are doing. Georgia—just stepping back from a law enforcement perspective—is at the center of the cybersecurity world. If you look at the private sector, about 25% of all global revenue now touches a Georgia company, and a lot of that’s because of Georgia Tech and the industry that we’ve created here. You’ve got the fintech industry where 70% of all North American transactions now touch a Georgia company. As I was told by a past U.S. attorney, it’s kind of like [how] the Southern District of New York became the hub for financial crimes, the Northern District of Georgia has become a hub for online financial crimes and cybersecurity because it all runs through our network. So you’ve got that; you’ve got the GBI doing cyber training in their new facility over in Augusta.

As far as the eye can see, cybersecurity and data protection is going to be an issue and knowing that a lot of these human trafficking crimes occur online, we’ve actually sent one of our prosecutors over to the U.S. attorney’s office for a year. She’s just come back to train on cyber crimes. It all goes hand-in-hand. You’ve got to be communicating. You’ve got to break down silos that have traditionally existed and look at the world in a whole different way. At the end of the day, it’s got to be about knowing and having the relationships, federal, state, local, whatever it takes to be able to go after these crimes, and they get more complex all the time.

Last question: what do you think that other state—looking at what Georgia’s recent been doing, from a criminal justice perspective—what are some takeaways that you think they could benefit from emulating?

I think what we’ve done on gang activity, raising awareness, getting everybody in the room to start talking about it. Again, first time ever, through our Georgia’s anti-gang network, you had U.S. attorneys, FBI, postal service—at the state level, you have corrections, community supervision, juvenile justice, our office, GBI, sheriffs, police chiefs, the DA’s. Everybody was at the table. That had never happened before.

So sort of like an emergent property of them getting together?

Everybody getting together, saying, “What do you hear,” “What are you seeing,” and, by the way, that’s the individual actually handling this. Oh good, we’ll start working together going forward. To raise awareness—when a governor makes an issue an issue, that matters. And having a governor that’s willing to talk about this and be willing to put the resources behind tackling it. And it’s been picked up in the media. Folks recognize that there’s gang activity, and they appreciate knowing there are solutions out there, and there are people that are willing to deal with it. And from a human trafficking standpoint, standing up for this unit at a state level shows the priority that the state plays on this and the value that we place on protecting children. To be able to see that—to me—it sends a tremendous message.

Thanks, Chris. I appreciate your time this afternoon, [and] it’s always interesting to learn about what various attorney generals are doing in their states, and clearly this is the Georgia perspective.