“Today, it is science fiction that often carried the torch of the utopian aspiration.”

Introduction

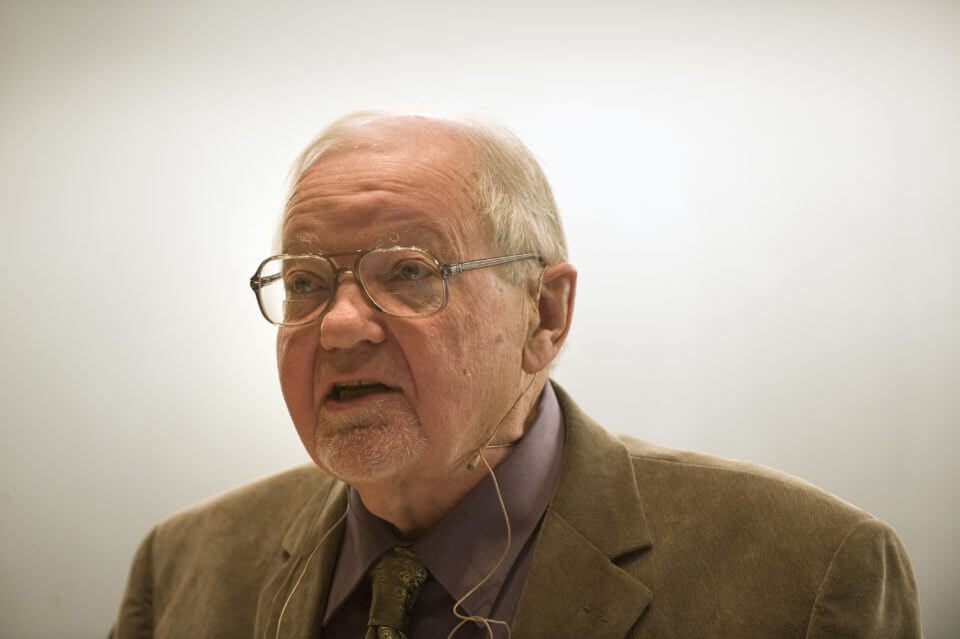

Fredric Jameson is among the acclaimed theorists in the world today, influencing areas from literary analysis to political philosophy. Critical theorists like the late Mark Fisher (discussed here), literary interpreters like Chaohua Wang, and many others have been inspired by his challenging but ever rich account of what Jameson calls “late capitalism” and postmodernity. Now in his 80’s, Jameson continues to be active with a new book Allegory and Ideology, which was released with Verso Books this year.

While it would be impossible summarize the richness of his work in this short article, I’d like to gesture to one of his more important ideas: the importance of science fiction and utopian literature as an artistic genre. He has written many essays on these subjects over the decades, but the most important source for understanding his perspective is probably the book Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, which was published in 2005. Jameson argues that the fascination with science fiction and fantasy which has developed since the 1970’s stems in no small part from a growing sense of anomie. We increasingly find it very difficult to change the actual world we live in, given that it is so driven by the influence of money and power. And so we take various forms of solace in the fantastic worlds of our imagination where it is still possible to contemplate a radically different future.

Jameson on Postmodern Culture and Late Capitalism

To the reading public, Jameson is undoubtedly best known for his work on postmodern culture. His interest in postmodernity goes back a long way, and one can find references to it as early as 1971 essays like “Metacommentary.” However, Jameson hammered away, in particular, on this topic in the 1980’s and 1990’s. In 1984, his seminal paper “Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” was released with the New Left Review and quickly sparked a storm of controversy. This was followed in 1991 by a book of the same name. In these pieces, Jameson argues that with the emergence of what Mandel called late capitalism, we also witnessed the development of a new kind of culture. In it, one saw the end of traditional ideologies and interpretations of everything from identities to value systems. This generated a very serious problem for post-modern subjects, who were unable to figure out who they were or what they should do by appealing to a living set of identities and values. What was instead available were the cultural products of mass media, presenting stereotyped and hyperreal images of the past. This offered a vampire-like power to live again on the sentimental nostalgia of the present. Many of us—eager and even desperate to find some bearing within an increasingly deconstructive post-modern culture—latched onto what Jameson called a “pastiche” of different tropes, identities, and values to help us make sense of the world. As he put it in Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism:

“This approach to the present by way of the art language of the simulacrum, or of the pastiche of the stereotypical past, endows present reality and the openness of present history with the spell and distance of a glossy mirage. Yet this mesmerizing new aesthetic mode itself emerged as an elaborated symptom of the waning of our historicity, of our lived possibility of experiencing history in some active way. It cannot therefore be said to produce this strange occulation of the present by its own formal power, but rather merely to demonstrate, though these inner contradictions, the enormity of a situation in which we seem increasingly incapable of fashioning representations of our own current experience.”

Almost paradoxically, this fixation on images of the past—whether it be drawing on the events of Nazi Germany as inspiration for villains in Star Wars or invoking the already dated 1980’s by bringing action heroes out of semi-retirement—reflects the fact that we are no longer really connected to history. As a historical materialist, Jameson, of course, finds this quite worrying. The more disconnected from the past we become the more necessary it is to draw from it in a museum-like fashion to construct hollow echoes of time gone by.

Jameson isn’t entirely pessimistic about post-modern culture. In some respects, it has opened vital cultural space to analyze identity and theorize on more emancipatory ways of being in the world. Moreover Jameson acknowledges that having a genuine relationship to past identities and values is necessary to frame new and creative visions for the future, but he also observes that too much fixation on what has been rather than what could be can turn someone into a reactionary very quickly. This demonstrates the importance of science fiction as a genre which has truly blossomed in modern times.

Instead of pursuing material benefits and social power, the humans and aliens of Star Trek often seek to better themselves through exploration and intellectual inquiry.

Science Fiction and the Fantasies of Possible Futures

Jameson’s work on science fiction finally puts the nail in the coffin of traditionalist “high culture” critiques of the genre. He takes science fiction and fantasy very seriously as works of art, which means the genres can both be praised for their aesthetic accomplishments and criticized sharply without recourse to the, “it’s just pulpy fun” excuse. In Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, Jameson focuses on one particular element of the sci-fi and fantasy genres: its relationship to possible utopian and dystopian futures. Jameson points out that the utopian genre has deep roots in Western culture. One could arguably trace the first utopian sketches back to Plato in The Republic carrying on through the work of writers like Thomas More and, of course, down to the often misplaced optimism of the socialists and communists today. Today, it is science fiction that often carried the torch of the utopian aspiration. Authors like Ursula K. Le Guin wrote novels about hypothetical futures where new kinds of human potential—in realms as diverse as technology and sexuality—could be explored with greater depth and complexity. Television shows like Star Trek: The Next Generation depict human societies which have largely transcended the problems of resource scarcity and inter-group animosity. Instead of pursuing material benefits and social power, the humans and aliens of Star Trek often seek to better themselves through exploration and intellectual inquiry. Jameson alerts us to how these kinds of genres—far from just being silly entertainment—can express deep yearnings on our part to believe in something better.

By contrast, the dystopian genre seems relatively new. While there have always been scathing and even apocalyptic critics of the course of events, the notion that a whole society could be arranged to make things worse seems to have sprung from the nightmarish experiences of 20th century totalitarianism and war. Aldous Huxley and George Orwell wrote about states where dictatorial leaders wielded absolute power over the masses, who were rendered ever more stupid and obedient through propaganda and mass communication. Phillip K Dick, who Jameson (rightly) considers the greatest science fiction author, relentlessly depicts a future where technology has advanced but human beings are more alone and confused than ever before. Dick’s anti-heroes often turn to drugs, alcohol and other distractions to divert themselves from the emptiness of their atrophied existence.

And contemporaneously popular culture is filled with depictions of dystopian universes. From The Walking Dead through Black Mirror, major forms of “entertainment” seem united in their conviction that the future is destined to be worse than the past. The most transparent of these depictions are found in the apocalypse genre, where humankind is literally wiped out, and it isn’t clear whether the universe is really worse off for our absence. In Cabin in the Woods, a 2012 horror film by Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard, the protagonists discover that they and other young people are routinely being sacrificed to demonic Gods in order to prevent them from destroying the world. Rather than the movie concluding with the protagonists sacrificing themselves for the greater good, they decided to let the world be destroyed. This is because any system or species which would allow innocence and youth to be annihilated to save itself is unworthy of carrying on. Everyone else’s love for themselves does not entitle them to sacrifice the few for the many. This pessimistic inclination is at the root of many of the bleakest dystopian works, which suggest that everything humankind loves will eventually destroy us.

Conclusion

For Jameson, the appeal of both the utopian and dystopian science fiction and fantasy genres lies partly in their describing futures which are very different than ours. Whether utopian or dystopian, they have the advantage of suggesting that something dramatic has happened, and it remains possible to change the course of history. Jameson argues that this is very different from our experience in postmodern culture, where the general sense is that everything of consequence has already happened and the only task left to us is raiding the sepulcher’s of the past the create grim pastiche like caricatures of identity in the present. He awakens us to the human desire for real history—and more importantly—the freedom to make changes for the better regardless of the potential risks.

Matt McManus is currently Professor of Politics and International Relations at TEC De Monterrey. His book Making Human Dignity Central to International Human Rights Law is forthcoming with the University of Wales Press. His books, The Rise of Post-modern Conservatism and What is Post-Modern Conservatism, will be published with Palgrave MacMillan and Zero Books, respectively. Matt can be reached at mattmcmanus300@gmail.com or added on Twitter via @MattPolProf.

Jameson wrote the foreword to a recent Vol. II of Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason, wherein Sartre actually tackles the topic of science fiction; to wit: “[]Readers of science fiction [seek] to recover an awareness of the being-in-itself of our history. But … some Martian … endowed with an intelligence and a scientific and technical level superior to our own, … reduces human history to its cosmic provincialism.”