“Modern society has always had a secret love affair with the criminal.”

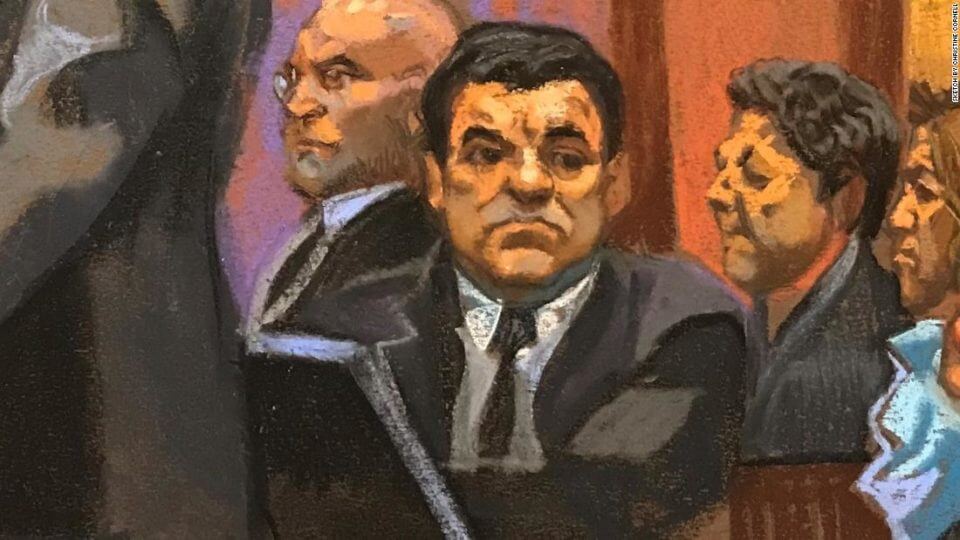

In a recent Merion West article, Dr. Gabriel Andrade offers a subtle rebuke to the glamorization of notorious drug lords such as Pablo Escobar—and more recently—El Chapo. Arguing that such adulation is both unsightly in sensationalizing bloodthirsty criminals and misguided in attempting to humanize those in Latin America profiting off the chaos of the War on Drugs, Dr. Andrade chides both Western thinkers on the Left and American popular culture for embracing such heinous figures. In his eyes, El Chapo represents more than just an edgy meme or a blot in the eyes of American imperialism; El Chapo is a twisted mirror into which the cultural and political sensitivities of modern society can be divined.

It’s clear that whatever the shortcomings of the War on Drugs, criminal drug lords such as El Chapo are beyond reprehensible for their crimes. One need only recall the grisly torture and murders ordered by El Chapo himself, as evidenced in a testimonial at his trial. Or one could look to the violent murders of several dozen students from a Mexican teaching college, who were arrested for their activism against government corruption and then handed over to a local gang to be butchered and left for the crows. Clearly, the perils of the drug trade have truly brought out the monster in man. But while Dr. Andrade correctly notes the complicity of criminals like El Chapo in the human tragedy that is the Drug War, he erroneously makes two vast and sweeping conclusions, one about the latent decadence of American popular culture and the other on the ethical conscience of Western leftists.

Andrade’s first error concerns the supposedly unprecedented nature of El Chapo’s popular stardom. He laments El Chapo’s popularity and compares it with the cult status of Charles Manson, though he qualifies it by admitting that Manson’s fandom was mostly confined to the mentally deranged. The unprecedented degree of fame attached to El Chapo’s persona represents—in Andrade’s view—a new low for American cultural decline.

While it may seem unsightly for a notorious gang leader to have a cult-like following in modern society, the truth is that we cannot be surprised by the fame that accompanies criminality in the modern world. From age-old cultural icons like Edward Teach (better known to posterity as Blackbeard the Pirate) and Western outlaw Billy the Kid, to more modern figures such as Prohibition gangster Al Capone and Depression-era bank robbers Bonnie and Clyde, modern society has always had a secret love affair with the criminal. Even today, society pays a premium for the entertaining antics of those stuck at the margins of mainstream society. The widespread popularity and influence of cult films such as Pulp Fiction and television shows like AMC’s Breaking Bad, both featuring the criminal element in its dramatic allure, are a showcase to the modern fascination with the criminal underground. And who can forget the hit television show The Sopranos, which forever made its mark on American popular culture with its unique narrative style and dualistic portrayal of the family man/mob boss, with one foot in the respectable atmosphere of suburban life and the other firmly entrenched in the cutthroat world of the mafia?

The reason for this not-so-secret tryst is perhaps not so complex: it arguably stems from the constraining and conformist aspects of modern life. Contemporary society is defined by its unprecedented capacity to shape and influence (i.e. constrain) individual behavior; this capacity takes the form of government surveillance, rule-dragging bureaucracies, intrusive employers, and the omnipotent panopticon of social media. The tedium of daily life often leaves little excitement for the average person, whereas the dark and imaginative underbelly of the criminal underground leaves open a whole world of possibilities. The criminal is a rebel, a self-actualized agent expressing his autonomy and agency by breaking down existing structures and norms and creating new ones. However reckless this vision may be—or however much blood pours as a result of it—the criminal represents one of the few “liberating” archetypes in modern culture, one that is shamelessly exploited by the demi-gods of television and film entertainment.

Interestingly enough, Karl Marx presciently observed the alienation present in modern society and which produces a need for “liberation” via popular entertainment. Contrary to some today, Marx did not reject the concept of “human nature” out of hand; indeed, he even offered a theory about the fundamental forces that drive human behavior. Marx argued that humans desire to produce new things, and that contrary to contemporary (and modern) moralists, the fundamental action of man is production, not consumption. By subjecting the individual worker to unseen and impersonal (i.e. economic) forces and controlling his behavior via regimented work schedules, modern (read: capitalist) society produces alienation by depriving the worker of control over his production process and treating him as a machine, interchangeable with any other worker and whose value is ultimately reducible to pure quantitative units (money).

Hannah Arendt echoed this perspective by observing that man is distinguished from animals and other lesser beings by his (or her) capacity to produce new things, a phenomenon she called natality. Because all humans are driven by this desire to create new things, whether in the form of artwork and institutions or the purely biological process of reproduction, any system that deprives humans of this capacity is fundamentally oppressive and detrimental to the individual.

With a society as all-encompassing and conformist as our own, it is only inevitable that the alienated masses flock to entertainment to serve as a release for their unfulfilled creative potential. It is no surprise that many of the most popular television shows in recent years have all incorporated a mixture of gritty realism, existential introspection, and varying degrees of historical adventurism and/or fantasy (Mad Men, Game of Thrones, The Man in the High Castle, etc). Criminal dramas serve as the ultimate combination of these three key themes, as they excite their audiences with the free-wheeling antics of groups and individuals relegated (in one way or another) to the margins of society. When the working day is done, regular people just want to have fun, and the best way of doing that is savoring the fantastical subscript of modern entertainment.

To be fair to Dr. Andrade, his fixation is less on El Chapo and his newfound popularity and more on his supposed enablers and apologists in left-wing academia. Chastising them for their libertine attitudes towards drugs, Andrade argues that leftist critics of the War on Drugs are unwilling to face the serious social and cultural problems that emerge from widespread consumption of “hard drugs” such as cocaine and heroin. Moreover, their systemic approach towards the issue of drugs and organized crime focuses too much blame on policymakers in Washington and too little on actual participants in the drug trade, i.e. El Chapo and other drug kingpins. According to Andrade, leftists (both in Latin America and abroad) are infatuated with the romance of a Robin Hood-esque bandit, a modern-day Pancho Villa who terrorizes the oligarchs of Latin America and redistributes wealth to the poor masses. This romantic fetish is the source for leftist apologetics for the actions of drug lords such as El Chapo.

Yet Andrade’s rather heavy-handed critique of left-wing perspectives on crime misses the mark. While it is true that the Left, at least today, is generally more forgiving of criminals and crime in general (at least in capitalist countries), Andrade fails to acknowledge how the advocates of the drug war have created the very criminals that they claim to oppose. As he himself concedes “Liberals are indeed onto something when they claim that the War on Drugs, if not a failure, at least requires a different approach.” To this point, he ought to have mentioned more specifically is that the United States’ various drug policies, from outright criminalization to underwriting other governments’ bloody (and often unsuccessful) militarization of anti-narcotics operations, have only increased the chaos and erosion of civil liberties without measurably reducing drug consumption or the power of the drug cartels.

Moreover, Dr. Andrade overstates his case on the issue of the Left’s favoritism towards the criminal and authoritarian element in Third World nations. Andrade cites the work of eminent historian (and noted Marxist) Eric Hobsbawm and the fawning praise given to left-wing caudillos such as Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez as evidence for the Left’s need to exorcise its own demons. Clearly, no self-respecting observer will deny the distastefulness of supporting authoritarian strongmen wherever they seize power and no matter what ideals they claim to champion. But Andrade is unwilling to give the Left the same nuanced perspective that he demands of them regarding the Drug War. Much electronic ink has been spilled over the failures of left-wing revolutionary projects and the black heart of totalitarianism that supposedly exists at the center of every left-wing political project, but nary a word is about the many crimes of Western policymakers ( and the tough choices they impose on leftist activists in and outside of the Third World.

Of course, Andrade is correct in asserting that the problems of drugs and crime run deeper than the sociopathic persona of El Chapo. Glamorizing drug lords and crime bosses may make for good entertainment, but it is a poor substitute for proactive policies that can end (or at least greatly reduce) the suffering produced by those profiting from the Drug War, those who have let the monster overtake the underlying humanity.

Elie Nehme studied political science at California State University, Long Beach.