“People do not truly want an end to suffering in all cases…They need challenges in order to feel the thrill of victory, guilt over their actions to have a chance at redemption, and the possibility of rejection and hatred to feel any deep form of love.”

Editor’s note: Following this piece, Matt McManus will on vacation until mid-August. As such, his next column will be published in around a month’s time.

Introduction

“’Plato, Rousseau, Fourier, aluminum columns—all that is good only for sparrows, not human society. But since the future form of human society is needed right now, when we’re finally ready to take action, in order to forestall any further thought on the subject, I’m proposing my own system of world organization. Here it is!’ he said, tapping his notebook. ‘I wanted to expatiate on my book to this meeting as briefly as possible, but I see it’s necessary to provide a great deal of verbal clarification; therefore my entire explication will take at least ten evenings, corresponding to the number of chapters in my book..’ (More laughter was heard) ‘Moreover I must declare in advance that my system is not yet complete.’ (Laughter again). ‘I became lost in my own data and my conclusion contradicts the original premise from which I started. Beginning with unlimited freedom, I end with unlimited despotism. I must add, however, there can be no other solution to the social problem except mine.’”

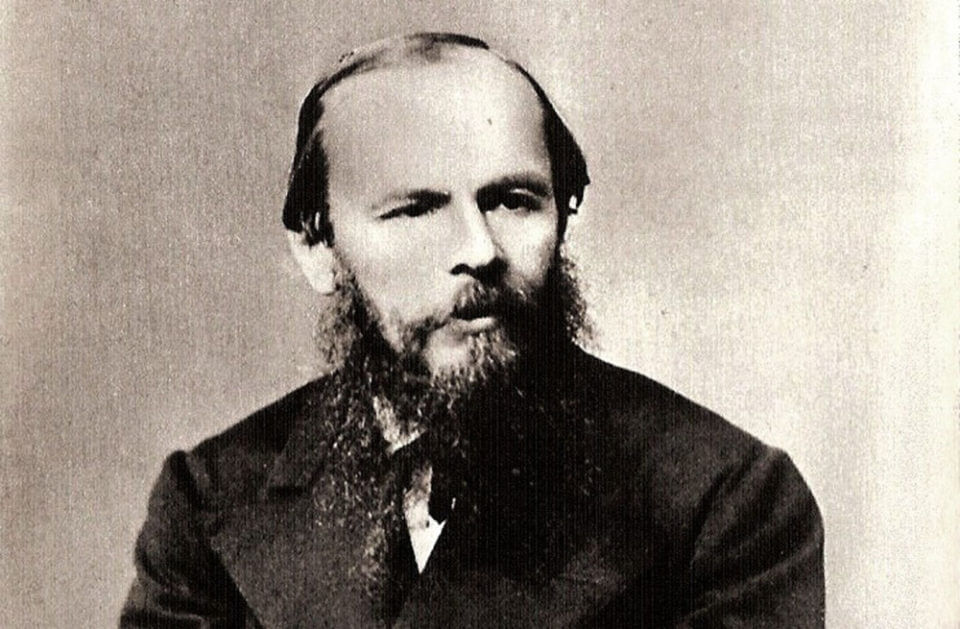

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Devils

In his great if overlong book The Devils, the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky weaves a black comedy about a group of radicals who want to take over a small Russian town as a stepping stone to a general revolution. Most of them parrot various platitudes about how their coming utopia will be best for everyone, expressing universal compassion and sympathy for the poor and dispossessed. But in their personal behavior, none of these conceits bear out. In their meetings, the radicals are vain, overestimate their abilities, and constantly seek to one up one another. Far from really believing in equality, each radical tries to outdo the others with their affectations about how much they care or by developing ever more radical “systems” to prove their genius. The parody reaches its pitch with the intellectual Shigalyov, who is the groups unofficial philosopher in chief. He gives a speech at their meeting expressing his alleged desire for the perfect society, but admitting that his original desire to achieve unlimited freedom ended with calling for “unlimited despotism.” It turns out Shigalyov’s system, the only “solution to the social problem” according to him, is about taking all freedom away from 90 per cent of the population and vesting power in the hands of a small group who is to organize everything. No credit for guessing who is to make up this group and lead the masses.

They are led by Peter Stepanovich, who is the unloved son of a low-level academic who has enjoyed some minor celebrity in the small town. Stepanovich is charismatic and manipulative, constantly agitating for revolutionary violence. In a moment of weakness he admits that ultimately his goal is not to bring about a utopian society. Driven by resentment at his father and the gilded life he embodies, Stepanovich ultimately wants power and violence for their own sake. He and his followers mask such demonic impulses under the guise of pleasant and smart sounding egalitarian platitudes and self-aggrandizing statements of compassion for the world. Dostoevsky ultimately compares these progressive radicals to the swine described in the Gospel of Luke, who were possessed by devils, ran into a lake and drowned. Dostoevsky predicated that the Satanic ideas propagated in 19th century Russia would lead to the destruction of their adherents and many other victims. Many regard this as prophecy, given what eventually happened once the Bolsheviks seized power.

Rather than regarding his aesthetic mission as drawing attention to the unnecessary suffering in the world, he came to see pain as a potentially purifying experience.

Unpacking Dostoevsky’s Critique

What gives Dostoevsky’s critique of radicalism its real bite is it comes from a knowing place. Early in his career the great novelist flirted with socialism and other kinds of utopian political projects. His early novel Poor Folk at points outdoes Dickens in its searing denunciation of a social order which would allow wretched poverty to exist in the midst of affluence. But Dostoevsky never cared much for the personalities of the socialist and utopian radicals, particularly their frequent emphasis on atheism and their attacks on the Orthodox Christian religion. After being arrested, nearly executed, and sent to Siberia for his radical associations, Dostoevsky experience a profound change of heart. Rather than regarding his aesthetic mission as drawing attention to the unnecessary suffering in the world, he came to see pain as a potentially purifying experience. Darker still, he pointed to how deeply many individuals actually crave suffering for themselves or others, whether out of feelings of guilt, resentment of the world around them, or simply to experience powerful emotions. The first of his great novels, Notes from the Underground, describes a very modern individual in the midst of an existential crisis. The titular underground man constantly tortures himself in part to give some sense of significance to his life, which he regards as meaningless and comical:

“I am a sick man…I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased. However, I know nothing at all about my disease, and do not know for certain what ails me. I don’t consult a doctor for it, and never have, though I have a respect for medicine and doctors. Besides, I am extremely superstitious, sufficiently so to respect medicine, anyway (I am well-educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious). No, I refuse to consult a doctor from spite. That you probably will not understand. Well, I understand it, though. Of course, I can’t explain who it is precisely that I am mortifying in this case by my spite: I am perfectly well aware that I cannot ‘pay out’ the doctors by not consulting them; I know better than anyone that by all this I am only injuring myself and no one else. But still, if I don’t consult a doctor it is from spite. My liver is bad, well—let it get worse!”

This theme continues down through Crime and Punishment where the anti-heroic protagonist, Raskolnikov, becomes influenced by a mishmash of modern radical ideas and decides to murder a vindictive elderly woman to take her money. Raskolnikov invokes utilitarian doctrines about the need to ameliorate his own suffering, that of his family, and ultimately all the people he intends to help once he gets himself settled. The woman he killed exploited the poor and was generally despised by all, meaning her death had little negative consequences for anyone. Raskolnikov also invokes proto-Nietzschean ideas about being a great man with a superior intelligence, which entitles him to take the steps he needs to achieve his ends. Much as Napoleon felt little problem with snuffing out the lives of whole armies on his road to power, why should Raskolnikov feel guilt at taking the life of a wicked old woman who the world is better off without? As in The Devils, Dostoevsky argues that things are not so simple. The guilt he feels over his actions makes Raskolnikov unable to relate to his friends and family—and more importantly to sincerely love the sacrificial and deeply spiritual Sonya. He tries to avoid getting caught for his crimes but is constantly told that the only way to actually relieve his deep suffering and guilt is to confess and accept punishment. In the end he chooses to willingly go to prison in Siberia accompanied by Sonya, in shackles but with the possibility of redemption held out.

Dostoevsky’s point in all of these works is that the influence of modern radical ideas is having a corrosive effect on Russian society. The most dramatic example is the way they are both undermining faith in traditional practices and religion, while driving intelligent individuals to embrace ever more outrageous and transformative ideologies which it will require immense bloodshed to enact. In this respect, Dostoevsky’s work is a powerful iteration of the conservative argument that permissive liberal modernity is undermining the stability of the world. But his position runs deeper than the usual traditionalist critique. Dostoevsky is arguing that the efforts of radicals to end suffering and bring about a utopian society—even if enacted in good faith—do not have a deep understanding of the real drives in the human heart. People do not truly want an end to suffering in all cases and will even bring pain into their lives simply to feel something. They need challenges in order to feel the thrill of victory, guilt over their actions to have a chance at redemption, and the possibility of rejection and hatred to feel any deep form of love. Like Aldous Huxley in Brave New World, Dostoevsky is powerfully arguing that progressive utopianism isn’t just doomed to fail but misguided.

Moreover, he points out that oftentimes the efforts of these radicals and reformers are not carried out in good faith. They are actually driven by a resentment of the world and a deep sense of arrogance. Raskolnikov and Peter Stepanovich invoke modern radical ideas to justify a belief in their own superiority and to avenge themselves against a world which has fundamentally let them down. Both consider themselves men of great intellect who should be entitled to kill as needed to achieve their goals. The superficial platitudes they invoke are lies told to others (and just as often to themselves) to mask a demonic impulse under the veil of compassion and modernization. They will bring ruin to themselves and anyone they come into contact with.

Conclusion

It is not difficult to draw parallels between Dostoevsky’s critique of radicalism in the 19th century and the arguments directed against so called social justice activists today. Figures like Jordan Peterson revere Dostoevsky because they see him as unmasking the dark truths behind both progressive doctrines and personalities. Much as the petty bourgeois radicals in The Devils sit around demanding people address them properly and policing the terminology used by their peers, today’s social justice activists demand censorship of ideas they dislike and invoke politically correct tropes to bully people into accepting their worldviews. And as with Peter Stepanovich, these actions belie a deeper and darker impulse to take revenge on the world by seizing control of it. This is why Peterson can say that the “philosophy” which guides the utterances of a Maoist and a trans-rights activist is effectively the same.

Dostoevsky’s critique of the Left is among the most powerful and knowing ever put forward—probably because unlike, say, those in the Intellectual Dark Web , he actually knew the positions of the Left well and had once deeply empathized with them. But I also believe it is highly flawed in a very deep respect. Dostoevsky was hardly a man lacking in compassion, as his staggeringly beautiful portrait of Christian love in The Brothers Karamazov proves. But his understanding of compassion is also highly individuated and personalized. Dostoevsky constantly emphasizes the small scale acts of mercy and generosity in life which give it meaning and their dialectical relationship to the suffering we must endure to have our attention drawn to the good. Yet, there can also be great and sincere love behind actions to make the world in general a better place.

Dostoevsky’s contemporary Leo Tolstoy knew this well, and his epic works like War and Peace offer a scathing criticism of aristocratic society and its indifference to the plight of the least fortunate in Russia. Tolstoy knew, as did Martin Luther King Jr., that though the arc of the moral universe may bend towards justice, that we have an obligation to help it along through creating just social conditions. This is an insight found in Tolstoy that is occasionally lacking in Dostoevsky and has bearing on his critique of progressive activism today. While it may be true that some activists are driven by resentment and a desire to revenge themselves on the world, countless more are giving of themselves to take incremental steps to eliminate the most pressing social ills of our time. These ills are exacerbated by political and economic indifference, which generate not just great suffering but also much evil in the world. We should do whatever we can to eliminate it.

Matt McManus is currently Professor of Politics and International Relations at TEC De Monterrey. His book Making Human Dignity Central to International Human Rights Law is forthcoming with the University of Wales Press. His books, The Rise of Post-modern Conservatism and What is Post-Modern Conservatism, will be published with Palgrave MacMillan and Zero Books, respectively. Matt can be reached at mattmcmanus300@gmail.com or added on Twitter via @MattPolProf.

I very much enjoyed that. A spirited fight back in the conclusion but Dostoevsky was well up on points.

PS Tolstoy tried to save Russia and arguably the twentieth century when he personally pitched Georgism (aka land reform, a very old idea) to the Tsar a few years before WW1.

Dostoevsky, like Nietzsche, was a profound psychologist – not only of individuals but of society in general. I believe Dostoevsky’s “conservatism” was grounded in a distrust of ideas disconnected from reality which is what he saw as symptomatic of modern thinking. He even claimed that increases in consciousness only arise from suffering, or more precisely, the transformation of suffering.

When Dostoevsky speaks of suffering (which he does often) I don’t think he simply means personal discomfort or pain. Rather, like the Buddha, he recognizes conflict as an elemental fact of reality. Modern thinking is very much thinking which takes on a life of its own because it has become dissociated from the elementary nature of experiential reality. This disconnect is what characterizes virtually all ideologies and particularly leftist ideologies.

Could you say more about your statement, “While it may be true that some activists are driven by resentment and a desire to revenge themselves on the world, countless more are giving of themselves to take incremental steps to eliminate the most pressing social ills of our time,” and the need to push back against “political and economic indifference”? It seems to me that much activism involving political issues has become ideological, harsh, and unbending in its righteousness. I also notice enormous generosity among certain “activists,” if that’s the right word, in the non-profit and religious realms who help people in quiet and hidden ways, but outside of politics. How many activist groups are seeking to change the economic and political landscape that do so with the kind of spirit that Tolstoy and Dostoevsky advocated? And who are they?

I wouldn’t be able to give you an exact number. But if you want a good example of a few I’ve worked and volunteered for, anything associated with local charities are usually pretty grounded and focused on helping. Amnesty International and Plan International both do good work in different areas.

You might want to change your opinion on Amnesty International

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/06/amnesty-international-has-toxic-working-culture-report-finds

Unfortunately, there is not much of a spirit of “volunteerism” in the left’s hard lean, despite their excessive claims to the moral high ground via open borders, and among other things like free college for everyone. The examples you give have ALWAYS existed, and truth be told, without the self-congratulating [self-conscious] need to force everyone to bow to it. Doing good deeds in secret, without fanfare, or compulsion [as Jesus encouraged] is what keeps social programming in check and out of the ridiculous realm of virtue signaling for political gain. Something else is going on today, and it has very little to do with the spirit of kindness and volunteerism. Lets not conflate the tradition of charity with social progressivism.

I am illuminated by reading Rene Girard, who has thoughts on “The Underground Man.”

In his conclusion, the author betrays his complete misunderstanding of Dostoevsky’s insights on human suffering and love; namely, by interpreting politically, or worldly, concepts which Dostoevsky understood as essentially spiritual, the author serves only to confuse the concepts. Had he understood ‘The Brothers Karamazov’, it would never have occurred to the author to write, “Yet, there can also be great and sincere love behind actions to make the world in general a better place.” On the contrary, actions with the sole aim “to make the world a better place” cannot be done out of true and sincere love, if only because such a sentiment is the vaguest of vagueries. Love, in the highest sense, can never be “in abstracto,” “in general,” etc. This is Dostoevsky’s point, and why he believed that if the world was going to be a better place, it is only by loving one another “in concreto,” – individually, or at least in community. Thus, while the human race en masse busily runs around attempting to exterminate what they understand as “social ills,” “political and economic indifference,” etc., the rate of suicide and suicide attempts by- please note- individuals, increases among the most affluent and politically free people in the history of mankind. “Oh, if we could only reduce the stigma of depression, or hand out anti-depressants in a care package through the mail, then our world would be a better place.” What nonsense! What utter pride, which seeks to boost one’s own ego with the self-satisfactory justification of “making the world a better place,” instead of humbly loving one’s neighbor in their suffering. By suffering with them in love –“personalized” and “highly individuated”. No, but the world could never live this way, could never be so humble as to give up its own markers of success, could never be so bold as to live by faith and love one another individually. Why? because there is no worldly reward. There is no money or honor or glory in such a life. “We had rather build a system,” says the world, “where we can quantify, identify, and annihilate ‘suffering’ en masse, so that we can assure ourselves that we are progressing — so we can pat ourselves on the back and finally live comfortably.” This type of pusillanimity is precisely what Dostoevsky wrote against. His message, in part, was one of willing, in a sense, suffering. Since, to love and to suffer are essentially one in the same. Since, to truly love in this world which is full of those who hate true love, one will inevitably suffer. No, his is not a call to attempt to rid the world of suffering, which is ultimately impossible and akin to cutting off the head of the hydra. No, his is a call to love in the midst of suffering, to suffer for love, in love. It is essentially a Christian message — which, of course, is “an offense to the Jews, and foolishness to the Greeks.”

Chris

Following your line of thought, it’s relevant to note that the etymology of the word “compassion” means “suffer with”. Today the word compassion seems to have been redefined as “paying someone else to suffer with”.

Brilliant comment. Where does the quote at the end regarding offence to the Jews and foolishness the Greeks come from?

Thanks, I appreciate that. The quote comes from 1 Corinthians 1:23.

Hi Chris,

Have you written any books? A blog? Twitter? Your comment so specifically addresses some ideas I’ve had recently that I would really enjoy reading more of your thoughts.

Hi Maxx,

Insofar as your question suggests that it is a possibility that I might have written a book, or the like, I am honored. Regretfully, I haven’t undertaken any such project, which to me seems so daunting, though I have often thought about doing so. In any case, I thank you for your comment, which indeed inspires me to begin such a venture. Nevertheless, in the interim–that is, between now and the publication of my own hypothetical book, or blog, etc.–I would enthusiastically recommend the author-ships of, in my opinion, two of the greatest writers to ever live, and by whom much of my thought is influenced and inspired: namely, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Soren Kierkegaard.

Chris,

Thank you for responding and thank you for the Soren Kierkegaard recommendation. If you do take on a blog or book, please feel free to share. goadmaxx@gmail.com

You may be skeptical to a fault.

This is a great point. The author misses out on the grounded God mysticism that Dostoevsky had integrated into his being and was working out from. This is not simply nature mysticism or soul mysticism or the monist standing on the top of a mountain all by themselves harping about their self-realization, as scholar of world religions R.C. Zaehner states in his own way. This is the truly religious way that the progressive socialist and the conditioned institutionalized religionist cannot go. It is the narrow gate that your worldly ideals and egotistical concepts cannot enter into. It is kenosis, or self-emptying, in the Christian mystical tradition. It is Krishna’s teaching to Arjuna in The Bhagavad Gita on true work. It is Jesus’s teaching to his disciples when he washes their feet at The Last Supper. True love is relational and not an abstract theory or philosophical concept. That’s why God is truly personal to God mystics of various religions. For God is the very ground of their being. Not in any kind of abstract sense, but in the fullness of their humble personhood. Spontaneous loving service flows out from this eternal fountain.

I saved this message over a year ago. I come back to it frequently. Is there any chance you would be open to an interview? I don’t have a podcast or plan on publishing so it would be closer to simple email correspondence. But, if you’d be open to sharing more wisdom I would be very appreciative.

Brilliant article. Stunningly prescient on Dostoevsky’s part to so analyze the true motives behind the cloaks of compassion. We see it all around us today. A worthy contemporary of Tolstoy. Like a light shining in the darkness, those things that are hidden in the secret places in mens hearts shall be shouted from the rooftops.

Good article until the last paragraph where the author feels compelled to defend leftist activists with a pathetic #NotAllLeftists screed.

The author wasn’t specifically talking about “leftists”.and by the way, not all so-called leftists are vain, resentful, or insincere pretenders like your comment seems to imply.

We cannot love without suffering. The two are linked in perpetuity – love always leads to suffering because in love there is always loss, separation and anxiety. Dostoevsky understood this dilemma well. It is true that some activists are disguising their resentment, however, many others genuinely wish to eradicate the conditions that lead to inequality, deprivation and suffering. Modern thinking is filled with angst, and modernists all tend to suffer from moral relativism when it comes to issues of personal responsibilites.

“We should do whatever we can to eliminate it.” This final sentence destroys the whole theme in my opinion. It seems to show the dark underbelly of the author’s desire and prove Dostoevsky to be more correct.