“While BTB is the most visible approach to signal support for reintegration, it is perhaps not the most effective way to bring about substantial criminal justice reform and truly help ex-felons build a new life.”

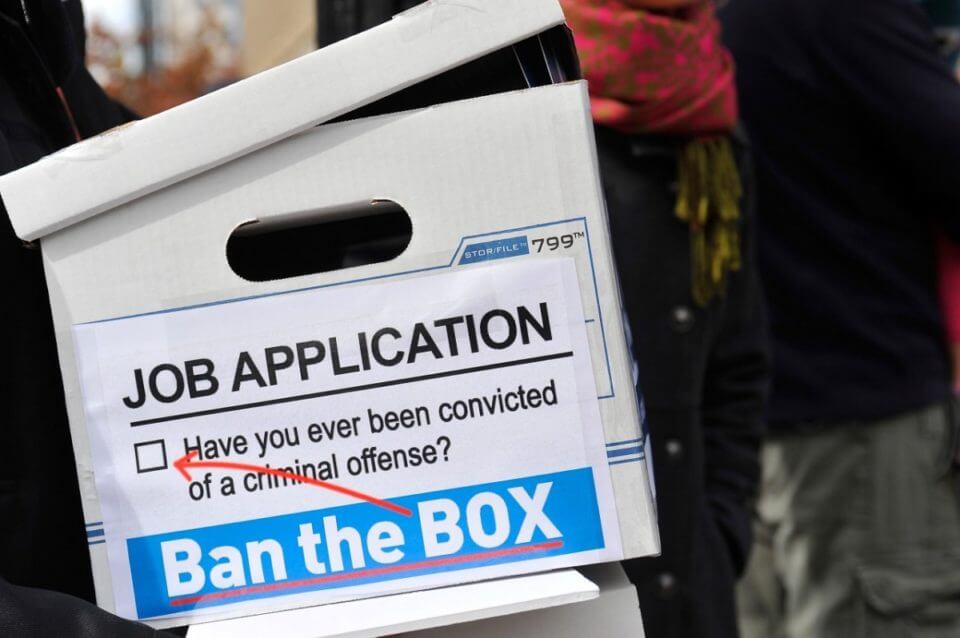

In January, some Duke University classmates and I were asked by the North Carolina Governor’s Office to write a memo about how to incentivize employers to hire more formerly incarcerated people. For a month, we researched several common policy options, including tax credits, staffing agencies’ guarantees, Ban the Box (BTB), post-conviction certificate, and support of state contractors that employ ex-felons. BTB is, of course, the recent grassroots effort that aims to stop employers from asking candidates about their criminal history on a job application form until later in the hiring process. In the end, we decided to drop BTB, which was and still is the most popular approach, and instead recommend supplementing federal tax incentives, along with expanding access to rehabilitation certificates and prioritizing contractors who hire ex-offenders.

About a week after we submitted the memo, we had a call with the correspondent from the Governor’s Office who told us that they are actually deep into the process of considering banning the box. She did not mention that they wanted to look at any of the other policies we had proposed to help with ex-felon employment. We walked out of that call feeling a little down and confused.

The hope of BTB is that employers can give ex-offenders an opportunity to tell their stories and prove themselves beyond what their history presumes. The movement has caught on. As of 2018, 33 states have officially banned the box, and over 150 cities have taken the initiative to adopt this policy at the municipal level. Although North Carolina has not adopted statewide BTB laws yet, many cities and counties, including Asheville, Buncombe, Carrboro, Charlotte, Cumberland County, Durham, Durham County, Forsyth, Mecklenburg, Spring Lake, Wake County, Wilmington and Winston-Salem, have banned the box on public-sector job applications.

Moreover, though BTB fulfills the public’s desire to expand civil rights and liberties, it still preserves the social and political ordering that pins ex-offenders as second-class citizens. In this sense, BTB is like a window dressing and shifts our attention away from demanding more comprehensive reintegration reforms.

However, at the time of our research, findings about BTB were mostly dominated by criticisms of its unintended negative consequences. In 2016, one study done by Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr from Princeton University created fictitious job applications for private-sector positions in New York City and New Jersey and found that BTB significantly increased the racial gap in callbacks from 7% to 43%. White applicants are much more favored than racial minorities after BTB because employers start using racial stereotyping as a substitute of criminal history.

Published around the same time, another study, conducted by Jennifer L. Doleac from University of Virginia and Benjamin Hansen from University of Oregon, covered both private and public sectors and found that “banning the box” lowered employment for young, low-skilled black men by 5%. These researchers believe that removing employers’ access to job applicants’ criminal record does not remove employers’ desire to still want to know, thus inviting racial profiling.

Although these findings are not universally supported, they have indeed shed some light on the impact of BTB laws. While BTB is the most visible approach to signal support for reintegration, it is perhaps not the most effective way to bring about substantial criminal justice reform and truly help ex-felons build a new life.

The problem with BTB is that it doesn’t directly address employers’ concerns when it comes to hiring formerly incarcerated people. Even though some ex-offenders might be able to build rapport with employers during interviews, many companies are still held back by concerns for workplace productivity and risks of lawsuits. BTB by itself also doesn’t help ex-felons acquire more skills or pursue further education to make up for the schooling and vocational training they might have missed. Under BTB, even the lucky ones who are able to find a job are often locked into low-skilled labor work and continued cycles of poverty. Thus, BTB remains largely symbolic. The reason why it can get easily passed is that it demands very little from both the companies and the government. Employers are still free to discriminate against ex-offenders—just not right away—while governments don’t have to invest money and human resources in more comprehensive reintegration efforts. Moreover, though BTB fulfills the public’s desire to expand civil rights and liberties, it still preserves the social and political ordering that pins ex-offenders as second-class citizens. In this sense, BTB is like a window dressing and shifts our attention away from demanding more comprehensive reintegration reforms.

But that is not the original purpose of BTB. In fact, it’s exactly the opposite. According to Dorsey Nunn, a co-leader of the movement, “We decided to push Ban the Box to organize people with criminal records, not the other way around, meaning we did not organize people with records to only pass Ban the Box policies. That was not our primary objective. For us the larger objective was to get people with criminal records to become organized and active in the fight against mass incarceration and the second-class status that comes with a criminal record.”

Thus, when we ask employers to keep an open mind in the hiring process, we should also advocate for other visible and straightforward policies to further encourage employers. When we urge the public to give ex-felons a second chance, we should also demand that the topic of criminal justice be given the focus it deserves in the upcoming election. When we applaud the discussions about rehabilitation and reform that BTB has opened up for us, we must not forget the bigger picture of pushing politicians and lawmakers to end mass incarceration and injustices.

Eva Hong is a student at Duke University and an intern at Merion West.