“On campuses so far, I have been pleasantly surprised that I have been invited to talks that have been well-received and civil.”

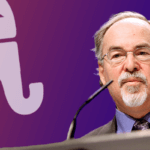

Greg Lukianoff is the president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), an organization that seeks to promote First Amendment rights of American college students and faculty members. He co-authored the 2018 book The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure with Dr. Jonathan Haidt. Mr. Lukianoff is also the author of Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate, which examines the state of public discourse on college campuses. He joins Erich Prince and Merion West to discuss his experience collaborating with Dr. Haidt on the book, reactions to their work, as well as his upbringing and lessons that cognitive behavioral therapy might shed on campus political debates.

Mr. Lukianoff, thank you for speaking with us today. In your book, you and Dr. Haidt talk about sitting down in Greenwich Village to discuss your plans for undertaking this project. You have written other books in the past; however, what is the main difference writing when you have a co-author? How does this process differ from books one writes on his own?

Writing with a co-author is risky, especially if you are friends with the person. A lot of people have their egos tied up in the particular way they construct their prose. Something that was really helpful in writing with Haidt was understanding that he is a phenomenal writer and trusting in that. The way we ended up dividing it up was I took the lead on most the preliminary work, the structure, some of the ideas, and researching some of the major incidents. As we got to the end of the book, Jon added in a lot more about the science, data, and areas of his expertise from psychology to Emile Durkheim and really perfected the wording. All throughout, we got fantastic help from the staff at FIRE (The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education), especially my chief researcher Pamela Paresky and my assistant Eli Feldman. We got careful, thoughtful help and feedback from dozens of people and we were so thankful that we even put the acknowledgments up online so even people who did not read the book could see them.

Jon is incredibly gifted as not just a writer and editor—but as a re-writer as well. A lot of times as a lawyer when you re-write, editors can think they are only changing something slightly but by the way they reword it, something can go from being technically legally correct to simply wrong. Jon is very skilled at taking very complicated ideas and explaining them clearly.

You dedicate this book to your mothers. An interesting point throughout the book is how children born beginning around 1995-1996 started to have a different sort of upbringing than children born prior. Can you talk about some of the differences between these young people and childhoods of the past—how your mothers raised you, so to speak?

My upbringing was dramatically different than the way that I will be raising my own kid in a lot of ways. Part of it was the fact we were first generation immigrants to the country and very broke for most of my childhood. Plus, my parents were divorced, and being the youngest meant that my parental figures on a day-to-day basis were my older siblings. That is not a system I would really recommend for everybody—and not one I claim is perfect and that we should continue to do it as we did back then. Certainly there were strengths to how people parented back then, and the fact everyone took for granted was that kids should be outside and playing a lot. This is more important than we realized at the time and one of the most pleasurable chapters to write for the book was the one about the importance of play in the development of all mammals.

I have a 3 year old and a 1 year old and am very adamant not just about making time for play—but for free play where the child decides what he or she does. Also if possible, with other children—in a group of children who are mixed in terms of age and background.

Another way my mom influenced me is that she is British, with those sensibilities that can be described as “a stiff upper lip.” I spent most of my life watching that way of life be put down and mocked but really that is a misunderstanding of what the wisdom of British stoicism really is. My mom is a very warm person, but a lot of the British norms about emotions and interactions are about the autonomy of your friends and the respect for space. Sometimes you do have to talk yourself down. However my Russian father would sometimes talk himself up: where you find yourself a little sad and then convince yourself about why you should be sadder. Mom would talk about how in some situations it is perfectly okay to distract yourself, but if you are feeling particularly blue, feel free to take the weekend to mope around but be back on Monday. This is sometimes described as just telling people to get over it, but they are really very functional ways of dealing with your emotions in a way that is really constructive.

Did this differ from how your father might advise you to get over a bump in the road?

My father is Russian; in Europe, you are hard-pressed to find any cultural normals that are more different than Russian and British. I think that Russian culture has a strong value of loyalty to friends, which is very positive. A strong sense of directness to the point where Russians sometimes come off as rude to Americans. When it comes to how you deal with emotional ups and downs…Well, I can’t assume my father is the end-all-be-all of all things Russian, but he did have a tendency to wallow and go deeper into moments when he was depressed, moving gradually from sad to despondent. Whereas, I recall moments where I would be in a terrible mood, and I would be hypothesizing about all the things that could be going wrong and my mom tells me, “You haven’t had any protein today, how about having some cheese?” I remember being super offended because I thought, “This is not about cheese, mom,” but then having some, I actually felt better.

I guess mother knows best?

Exactly. My mom’s much maligned “stiff upper lip” was far more functional than my dad’s “let’s see how sad we can make ourselves” approach.

So I think this may be a good moment to focus on the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy aspect that you bring up a lot in the book. What was it like to channel your own personal experiences to apply it to the situation nationally?

I had always had issues with depression as you can probably tell from my talking about it. It kind of runs in the family.

You spoke candidly about this on Twitter recently.

Yes, I did. I got very explicit because sometimes people can be very hard on people who commit suicide and get angry at them. Wondering “How dare they do this to me,” with a little bit of an assumption that people are in their right minds in that state. The thing that I felt I needed to say was back when I was at my darkest and deepest in 2007 where I had to get myself hospitalized, I really kind of thought if I asked my brother and sisters if they would help me kill myself they would actually do it. That is insane. It is the kind of thing that when you are in the kind of depressions that lead to suicide attempts, a lot of the times people are not themselves so to speak. They’re in a bad way.

So yes, this all happened about two years after I started as president of FIRE (The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education). And I will say that it was in part due to the difficulty of being in the middle of the culture wars at the time. It was exhausting. People who are 100% on your side in a free speech case when the speech involves someone they like—can suddenly curse you to high heaven when it is from someone they they don’t. It can be very isolating and was in many ways. After this terrible bout in 2007, with the addition to help from therapists and medication, what helped me long term was Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. This also agrees with my mother’s approach—and also with my own way of processing things where what you did is look at those exaggerated voices you have in your head telling you that if something goes wrong your life is over, and realize that 999 times out of 1,000, it isn’t really over.

This is the antidote to the advice offered by the fictitious Greek sage in the book that tells you to listen to that voice in your head?

Exactly. I was learning all of these techniques for talking down to my exaggerated voices, while working on campuses where I felt administrators were sending the opposite message—which was you are in great danger, or very fragile, and if you are emotionally hurt, you won’t bounce back. All of this dysfunctional stuff I was learning to talk back to in my own head, administrators were demonstrating to students often unwittingly, usually to engage in cognitive distortions. That is what really got me thinking about the relationship between CBT and free speech on campus.

What really made me decide to talk to Jon about this was the shift we saw in 2013-2014. And during the entire period from 2007-late 2013, I was seeing cognitive distortions modeled by administrators; students themselves didn’t seem to be buying it or trying to emulate it. Students understood freedom of speech very well. But it was around 2013-2014 where we started seeing student demands for censorship, them not allowing voices to speak on campus.

We really started seeing this around that time, but the rationalization for these around that time were really being framed around psychology. People were saying, “I do not want to talk to this guy around campus because it would really be psychologically traumatizing” usually not to the speaker but to others on campus. That just didn’t sound right to me at all and felt like dysfunctional ideas of psychology.

A particularly striking part of the book is when you say that, “avoiding triggers is a symptom of PTSD and not a treatment for it.”

It is interesting because students, in particular, are really defensive of trigger warnings. It comes as a slight surprise that this thing professors sometimes do for students, which aren’t all that common at most schools, is something people are really defensive about. The thing I have to explain every time this comes up in a talk is 1) there is no evidence that trigger warnings are helpful to people who have PTSD, which is the major claim that is made about them. 2) There is lots of mainstream evidence, and even one study, that says they may be harmful to students. They raise people’s sense of anxiety, including in people who never had any anxiety around those issues.

I think the best way it was explained is it is like playing scary music in a horror film. Essentially with trigger warning, say about violence in a book, it may make it a bigger deal than it would be otherwise. So we always say that research indicates that it may actually be harmful. And lastly 3), you have to consider that it puts professors in a situation where they may be hesitant or nervous to talk about something that may be essential to teaching adult students.

I want to ask you how the book has been received in your view. First by the media. I saw your interview with CBS This Morning, for example. Secondly, how have the responses been on various college campuses from deans to students and in general?

We were pleasantly surprised by both the original article we wrote in 2015 and the book. Both were positively received and produced very thoughtful comments among people who may not even agree with it. It led to a high level of discussion about serious issues and had very few serious attacks in the media. Some of those that we did see were mostly guilt by association attacks that had nothing to do with the book. I remember reading some amazing piece in The Guardian that we were favorably quoting Solzhenitsyn—and that Jordan Peterson was writing a forward for Solzhenitsyn. Of course, it was apparently assumed that readers thought he is evil, so we must be evil. It really wasn’t really so much an argument, as a litany of odd attempts at guilt by association.

On campuses so far, I have been pleasantly surprised that I have been invited to talks that have been well-received and civil. I do, however, see when you watch this on Twitter that some of our harshest critics are those who have no idea what the book actually says. Most of the criticism we see on campus is from people who don’t like what the title implies. The president of Northwestern talked about our article when it originally came out by saying these imbeciles don’t believe that microaggressions exist. But nobody really believes that microaggressions don’t exist. The question is whether or not we should be policing them or what the definition is. It’s been interesting to see that some administrators think they can score points with students by blasting the title of the book.

You said at one point in the book that a faux pas doesn’t make you a bad person, and maybe some of these microaggressions are more of the faux pas variety than having any nefarious intent behind them?

Let’s be clear here. Microaggressions are absolutely a fascinating topic. By all means, let’s find out the ways we slight each other. But if you create a situation where any interpretation that could be seen as discriminatory could be seen as true, then it doesn’t matter what your intent is. It the way speech is then interpreted on most of the campuses is the by the norms of usually upper and upper middle class administrators who live in a highly “group-thinky” environment, which can bounce back and forth from sounding tolerant to sounding Victorian to sounding like Portlandia.

Since both of my parents grew up in foreign countries, my dad talks about how if you show up to an environment and just assume that everyone has to adjust to your way of speaking and talking, you are (in Russian accent), “Acting like a hick.” You are just transposing your politeness norms onto other people. So there’s a reason that people have to be so careful about these ideas in higher education; it is no surprise to us that we hear from people from different economic backgrounds and from different parts of the world showing up on campus and not wanting to engage with topics because they realize there are so many landmines for anything controversial.

Does it seem these days that there is a role reversal, where now the college dean or president is serving the students instead of the other way around? Seems a far cry sometimes from Merle Haggard singing “that the kids still respect the college dean.”

Yes. That is something we really see in this Sullivan case at Harvard where they are trying to get a dean removed from his job at a residential dorm because he criticized due process in a harassment case at Harvard and represented Harvey Weinstein. In this case, universities have been too patient with claims by students where they don’t understand the right to insult or the right to freedom of speech. In order to stop these cases cold, you need some presidents that will stand up early and often and say, “I understand you may not want this man to be the head of a dormitory, but he is going to be that; and we are not going to undermine his freedom of speech and his ability to defend people that you may dislike.”

I remember in 2015 the students put together almost a Martin Luther-style 95 Theses and marched on the president of Yale’s house on Hillhouse Avenue asking for their demands.

What Yale should have done in that circumstance, early and often, was state clearly, unapologetically, unambiguously that Nicholas and Erika Christakis will not be punished for what they say period. They should have said it very publicly and very early

Thank you for speaking today, Mr. Lukianoff.

Thanks, Erich.

LBut nobody really believes that microaggressions don’t exist.“ – Yeah, maybe in your own self-deluded bubble. Most people that are either sane of don’t suffer from double digit IQs know that “microaggressions” are just one of many fabrications to make white people regret their heritage. Boo hoo, someone says they don’t see color and it’s now the end of the world. Take the clown shoes off you fucking imbecile!