“Just being a woman in politics has not necessarily meant supporting policies in favor of other women. For example, a deputy in Veracruz proposed establishing a 10pm curfew for women to avoid more femicides in her state.”

Women all over Mexico are afraid in their everyday lives. We are afraid to take the metro and be taken or assaulted, but we must work and study. We are afraid of partying because someone might just rape us, but why must we stay hidden? We are afraid of walking down the streets on our own because we might get killed. The reality is that we are afraid of living in a country where the powerful and influential have chosen to ignore us. I understand from my experience studying abroad that women are afraid all over the world because rape, sexual assault, and gender violence have no nationality. However, upon my return to Mexico I realized the situation is far worse than what I ever imagined.

Yet no matter how hopeful I am, I cannot help but wonder if having more women representatives will actually translate into a decrease in gender-related crimes such as rape, femicide, statutory rape, and sexual assault.

The 2018 elections were ground-breaking for gender equality in Mexico. For the first time in history, the country had elected 50% of women in Congress and named a gender equal cabinet, with the first woman as Secretary of State. For girls and women all over, having a more female political body sounded hopeful. Yet no matter how hopeful I am, I cannot help but wonder if having more women representatives will actually translate into a decrease in gender-related crimes such as rape, femicide, statutory rape, and sexual assault. Could it be that no matter how many women enter the political scene, we will still be disenfranchised and unable to see past Mexico’s internalized machismo? I decided to review plenty of government databases and reports on gender violence, and the results were frightening, especially because available data only shows the number of reported crimes to government agencies and the real number must nearly double, having at least 1019 femicides between 2015 – 2018. Not only was there an asymmetry in the information presented officially by different governmental agencies, but, in fact, it seemed as if the government is knowingly hiding facts and figures. Additionally, I searched for the number of female political representatives as well as their proposals, and any glimmer of hope I had just vanished. In this article, I present both the most horrifying and optimistic numbers I found.

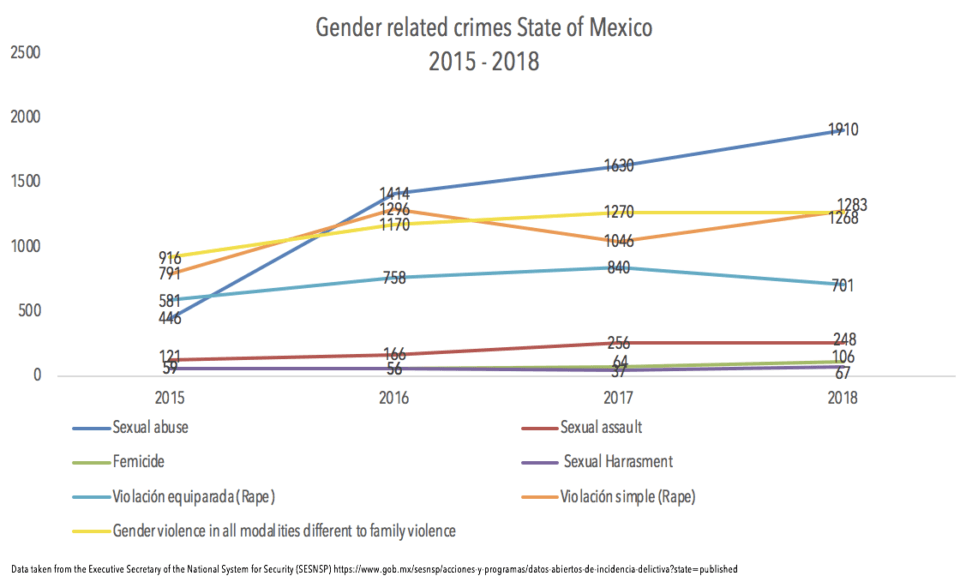

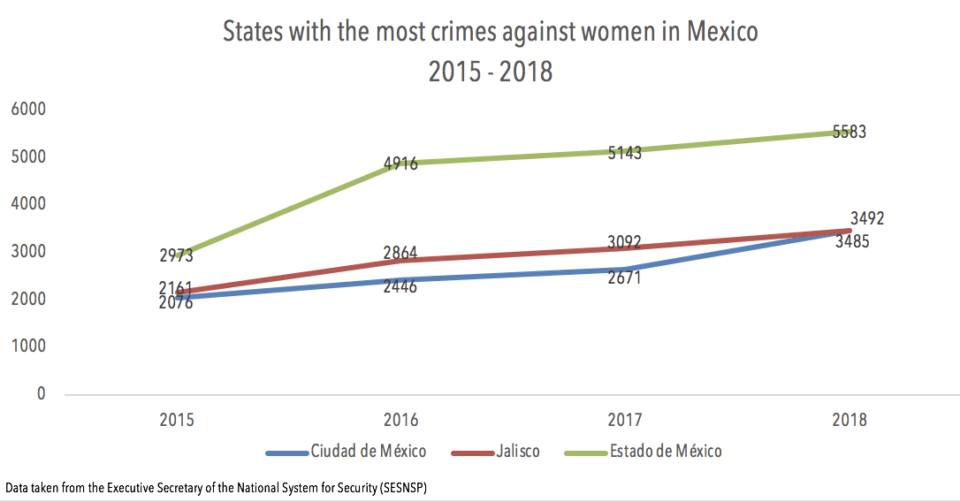

A couple of weeks ago three girls were taken just six minutes away from where I live. They were hanging out in the local coffee shop when some men took them away in a van. One of the girls managed to escape and plea for help. This is an everyday story in the State of Mexico. Families being dismembered and young girls losing their dreams forever. Historically, the state where I live has had some of the worst rates of gender-related crimes; just between 2015 and 2018, they increased by 82%. In these years there have been 18,615 reported crimes that include sexual abuse, sexual harassment, femicide, sexual assault, rape, and gender violence outside the household.

Due to the stratospheric number of women being assaulted or killed in the State of Mexico, since 2015 the government declared a Gender Alert (solicited since 2011), which consists of a set of emergency actions to confront and eradicate femicide violence in a determined territory exercised by individuals inside their communities and backed-up by the Secretary of State (SEGOB). Most protocols and laws to prevent gender violence have been ignored by the authorities of the state, having no local protocol to protect women even when some of the most gruesome cases like El Monstruo de Ecatepec have occurred in the state’s municipalities. (In this case, Juan Carlos “N” and his wife, kidnapped and murdered at least 10 women in the most ghastly ways. They were detained after being found with a stroller full of human remains.)

In addition to the lack of action, it is important to point out that the State of Mexico has only 30/66 women representatives in the national Chamber of Deputies and one female senator at the national level. The most dangerous state for women and girls has a rooted female political disenfranchisement and machismo, preventing equality from happening.

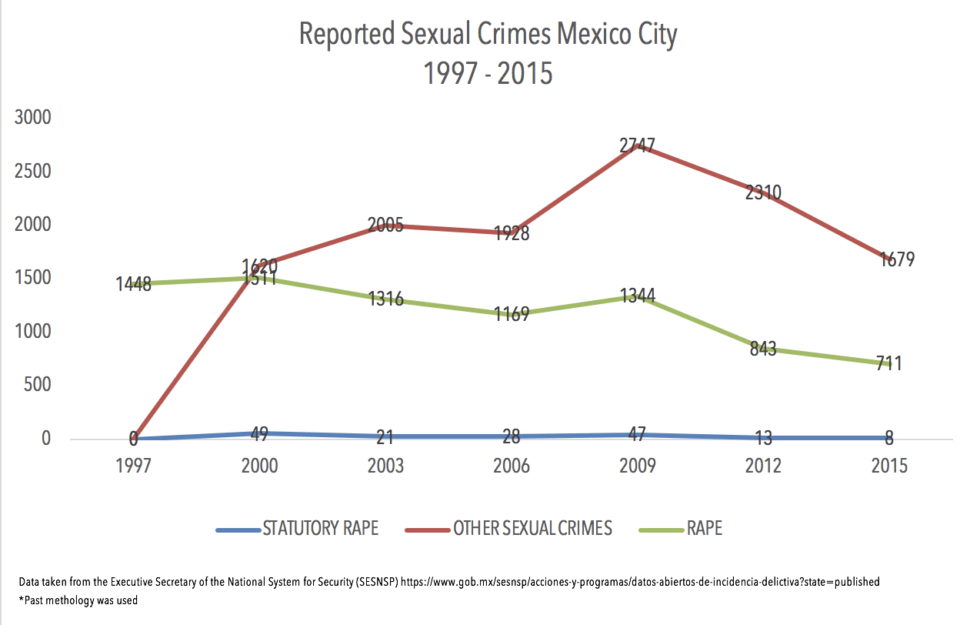

Mexico City is the country’s capital and my future job destination; however, I am equally afraid to go out on my own and have to take precautions every time I leave home. Most of the locals and people traveling from the metropolitan area of the city (located in three different states) use public transportation to get around. Recently assault and kidnapping cases in the Mexico City metro system have caught the eye of media outlets, but such crimes have been happening for years. All the while, pleas for help have mostly been ignored. Authorities are now turning to mechanisms to help victims report assaults or any suspicious behaviors by men; nonetheless, shaming and victim blaming continues to be a problem. Claudia Sheinbaum is the first governor of Mexico City—being the second woman in history to be the head of the country’s capital (the first was Rosario Robles as interim in 1999). But she has been criticized for not taking enough action to prevent and eradicate gender violence and related crimes, even when keeping mechanisms and protocols implemented in past administrations.

By virtue of the government’s inefficiency in addressing the rise in gender violence, several organizations and civilians have been forced to come up with initiatives to combat the wave of attacks against women. For example, the #SafePlaces campaign was created, in which shops and restaurants volunteer to be safe havens in case one feels endangered. Another campaign that emerged in the last few weeks was #MeEstanLlevando, which promoted collective defense for women who cried out for help. Governor Sheinbaum stated that the campaign was created by her adversaries to use it against her. Being a woman herself this is somehow a selfish claim, especially after having at least 48 open files of attempted kidnapping in the Mexico City metro. The campaign has already been taken down.

With the escalation of violence since Sheinbaum started her administration, representing at least a 10% increase compared to January 2018, the capital has had some of the highest rates of reported sexual and gender crimes in the country since the 1990’s. Despite the rise in gender related crimes, political equality in Mexico City has slightly risen. In the present administration there are 26/47 female deputies as national representatives for Mexico City in Congress and one senator, as well as five women candidates for governor before Sheinbaum was elected.

There does not seem to be a relationship between the number of politically empowered women and a decrease in gender related crimes.

Jalisco is mostly known for its tequila, its growing metropoli, and the traditional mariachi. However, in recent years it has also been recognized as one of the most insecure states in the country, especially due to the rise of violence against women. Jalisco is home to one of the most important and industrialized cities of the country, but it is also home to 10 municipalities with an active Gender Alert. From 2015 to 2018, the number of gender related crimes has gone up by 61%, with a total of 11,602 reported felonies. The amount of femicides reported by the SESNSP has nearly doubled in just one year, with 48 femicides in 2018. As I analyzed the data on femicides, I realized something was off; the number seemed too little for a state plagued by violence and machismo. I decided to search for an unofficial and more reliable source of data and came across the outrageous number of 171 femicides in 2018, mapped by Maria Salguero in FeminicidiosMx.

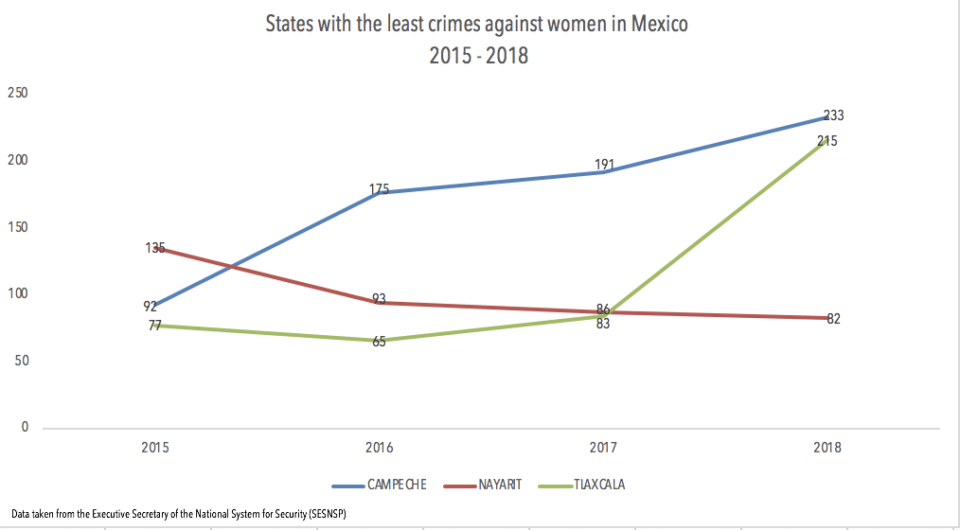

After reviewing the situation in the three states that have a larger impact on working class women such as myself, I compared them to the states with the least amount of gender violence in Mexico. In some places, the results seem fairly more optimistic. However, even the “best” or supposedly safest states for women to live in, have a ridiculous amount of reported gender crimes. Let’s take for example Nayarit in the western part of Mexico, which reported the least number of gender violence in the country, having only 396 cases between 2015 and 2018. In spite of this, Nayarit has 7 municipalities with Gender Alerts. The state has 6/8 women as deputy representatives, but there does not seem to be a relationship between the number of politically empowered women and a decrease in gender related crimes. Very similarly, the states of Tlaxcala and Campeche present some of the lowest rates in violence against women but also have requested Gender Alerts in 13 and 8 municipalities respectively.

Even the states that seem to be the best destinations for women and girls in Mexico, have important increases in gender violence. Additionally, states with smaller populations—like Tlaxcala—present a worrying number of crimes against women. Strictly speaking, we are not safe anywhere.

Mexican authorities claim that more and more opportunities are being carried out for women across the country. This may be true to a certain extent, but how can we access these so called opportunities if the femicide rate has gone up in the last three years? If we are still being shamed and blamed for crimes against us? If we are still politically disenfranchised how can things really change?

While going through data of several government agencies I noticed that an important deal of information did not coincide. In fact, there are different classifications for crimes according to local laws, which makes coordination even more difficult. A major complication related to this is that not all states have regional programs or mechanisms to address gender violence—and instead rely on federal laws that have proven to be insufficient. Adding to the problem, some states have deliberately massaged numbers so they do not affect their public image or the image of those in power; some states even present a zero rate of femicides, which has proven to be untrue by NGOs and initiatives like FeminicidiosMx.

Massaged numbers and inefficient policies are only part of the problem. As I wrote a year ago, Mexico’s ingrained machismo does not only harm women at home or at work, it unquestionably impacts the way politics is conducted throughout the country. 66 years ago women in Mexico gained the right to vote and be elected to office. Since then, the country has had seven female governors, but sadly their presence has not solved political disenfranchisement nor has it dramatically decreased gender violence. Representation is crucial; however, just being a woman in politics has not necessarily meant supporting policies in favor of other women. For example, a deputy in Veracruz proposed establishing a 10pm curfew for women to avoid more femicides in her state. When I heard about her proposal, I was outraged. Nevertheless, I understood that we are still far away from deconstructing machismo within ourselves and our societies. The lack of questioning of our deep-seated machismo makes us think women should be accountable for situations where they are victims and not perpetrators. In other words, for many female politicians it seems easier to blame women and make them change their habits, their clothing, their routines—instead of attacking the root problem.

To be a strong supporter or member of the feminist cause and create better public policies or mechanisms that eradicate violence against women, one must understand the different contexts thousands of women are put into and question our own privilege. I was privileged enough to attend elite schools both in Mexico and the U.S., to live with my parents, and to access as much information as I wanted. Even with a comparative advantage over many women in Mexico, I have been exposed to situations of machismo, misogyny, and gender violence. We cannot have better policies and mechanisms, if we do not understand that these must be intersectional. Women, transwomen, and girls will continue to die, will continue to have little access to opportunities until those who have any type of privilege or influence actually raise their voices in favor of all. And even so, political disenfranchisement will still be a challenge, but we must understand that gender violence is consequential to the established social norms that reinforce machismo. It is not enough to have more women in power. We must eradicate patriarchal and machista ideals inside and out.

What happens in my country is not only related to gender and being female. It has also to do with race, age, socioeconomic status, and geographical context. Most importantly it has to do with the impunity and corruption in Mexico’s government. Those so-called monsters who rape and murder are a product of a rotten system that does not punish them and becomes deaf to victims. Such impunity exists in both high and low rank employees, policemen who contaminate crime scenes or agency directors who chose to ignore the problem. So if you are comfortably reading this piece elsewhere, think about your own context, can you do something to make it better? Are you part of the problem by being an aggressor or normalizing machismo or sexism? Remember, violence is not only rape or assault or murder; violence is having to be careful every second of the day: carrying two cell phones in case you get robbed on your way home, using your makeup mirror to see if anyone’s following you, texting your mom a photo of what you were wearing in case you disappear.

If we don’t act now, violence will continue to be normalized, thousands of women will continue to die, and the rest will continue to be afraid of being who they are. The fight against gender violence starts with fighting our own demons. I am hopeful that one day we won’t need to shout any longer #NiUnaMás #NiUnaMenos.

Verónica Lira is an honors graduate with a B.A. in International Relations from Tecnológico de Monterrey, who is currently focusing on gender studies and developing student programs against gender violence. She can be reached on Twitter @vero_alo.