“Any bill that’s passed by 100% Republicans and no Democrats or 100% Democrats and no Republicans is not the best piece of legislation that could have been forged.”

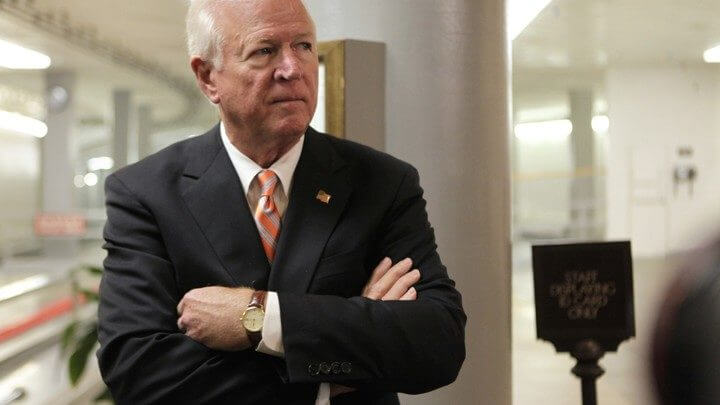

From 2003 to 2015, Saxby Chambliss represented Georgia in the United States Senate. During this time, he was known, in particular, for his work on behalf of national defense, a timely issue in the years following 9/11. He spent time as the Chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee and as the ranking member on the Select Committee on Intelligence. Prior to his service in the Senate, Mr. Chambliss served in the U.S. House of Representatives, entering in 1994 during the “Republican Revolution.” Here, he joins Merion West‘s Erich Prince to discuss his reflections on his career, the role of bipartisanship in effective governance, John McCain, and what advice he would most want to give new politicians beginning their careers.

Senator, good afternoon. Thank you for joining us. I’d like to begin by drawing attention to your recent appearance speaking at the University of Georgia. The Red and Black, the school newspaper there, discussed the portion of your remarks where you alluded to similarities between the political environment in the mid-1990’s and the divisions of today. Are some lessons from then particularly applicable today?

I was asked to speak to the College Republicans in Athens a couple of weeks ago. My comments about the divisiveness in the mid-90’s relative to today had more to do with the progression of the divisiveness between members of the House and members of the Senate, which is a reflection of the divisiveness of the country. In 1994—when I was elected—we were a group of very conservative members of the House. We were elected from all around the country, and the country had made a very conscious decision that smaller government and lower taxes were hot-button issues. That was the direction which America wanted to take itself. So we took control of the House for the first time in 40 years.

We developed over the years, within the Republican party, a hardcore right faction that began during that timeframe and moved further right with the Tea Party movement. Now, you are seeing a large group of members of the House on the far-right, but you also see the Democratic Party gradually start moving further and further to the left. So you not only have the hardcore members of the House on the right, but you have a hardcore group of members just as far to the left. That group that remains in the middle has usually been the group that gets legislation done. Now, it has become more difficult because the word “compromise” has become a four-letter word, and you see that same thing happen on the Senate side. You are seeing a larger group of folks on the far-right and a larger group of folks on the far-left, and it has just changed the dynamics of the Senate.

I do not pretend to even think that is a positive sign. When you had senators, who were willing to cross the aisle and work deals, legislation not only got done—but the type of legislation that got done was favorable legislation. Any bill that’s passed by 100% Republicans and no Democrats or 100% Democrats and no Republicans is not the best piece of legislation that could have been forged.

And you’ve received attention for your bipartisan work in the areas of deficit reduction, energy, and immigration reform. Do you imagine that it is harder to be bipartisan in 2018, as compared to when you were in office?

Very much so. It has become more and more difficult for members of both parties to sit down and take the best ideas from Democrats and the best ideas from Republicans and put those ideas together to legislate. It has unquestionably become more difficult with the 51 vote rule on the executive calendar. It is particularly difficult to get middle-of-the-road leadership in various agencies. You are going to get more far-left and far-right [individuals] in leadership roles within agencies of the government.

In previous interviews with other members of the Senate, we’ve discussed the importance of personal relationships across the aisle as being essential to forging bipartisan agreements. A number of these friendships have been widely publicized, including that of Joe Lieberman and John McCain for example. When you retired, Dianne Feinstein, for one, had some favorable comments about you and your service in the intelligence realm. What is the role of these personal relationships in finding the middle and passing legislation?

There is no question that personal relationships are critically important within the United States Senate. As long as you have to have 60 votes, you need to find the best way forward to get them, and that means that you need support on both sides. The Senate has always functioned best when those personal relationships were exhibited in the legislative process. It makes for unusual collaborations—such as Barack Obama and my good friend Tom Coburn. You could not have somebody more far-right and far-left. Yet they were able to work together in the legislative arena.

Likewise, Senator Kennedy would take somebody on the very conservative side from time to time and forge legislation. The personal relationships are of critical importance to make sure the right things are done legislatively—or otherwise—in the Senate. My relationships with Mark Warner and Senator Feinstein and other Democrats were very public, and with respect to Feinstein, they were in relation to national security. Mark Warner’s was more on the topic of fiscal responsibility. Those relationships were critically important to get good positive legislation work done.

On the subject of national debt, there has much discussion going on currently about whether this issue is more a campaign talking point than an actual topic members of Congress want to address. Senator Rand Paul, for instance, has talked about how Republicans claim to want to tackle the deficit. However, once they get into power, these talks fade away. Is this a concern you share?

Absolutely. Republicans are spending money at a faster rate than Democrats. I agree with Senator Paul. We are not as concerned from a Republican standpoint today as we were back when we were the minority.

Another issue that was a focus in 1994—and also came back up during the Trump campaign and Mr. Trump’s presidency—is the idea of term limits. This was part of the “Contract with America” in 1994 but has not been implemented. Is there still a desire on the part of the American people to see term limits for Congress?

Term limits were part of the platform that all Republicans and I ran on in 1994. That was documented within the “Contract with America.” It did not take me long to realize once I got to the House that we do have term limits. Term limits do not take into account how smart the American people are as a whole. They can figure out if you are doing your job or not. What I came to conclude was that formalizing the issue of term limits was not in the best interest of the country because you would lose some very valuable, experienced people, if you enforced term limits. The voters also have the opportunity to enforce these limits every two or every six years, depending on the House or the Senate.

So you are sympathetic to the argument that there is no substitute for the experience of veteran members of Congress when it comes to making difficult decisions?

Yes. I told my colleagues when I left the Senate that there is a time to get elected—and yet also a time to leave. You have to have a lot of self-reflection on that issue if the system is going to work the way that it should work. Sometimes that is hard to do since there is a lot of power associated with being in the House or Senate. Finally, you have to make up your mind that you’re going to give it up despite that fact that if you’re there longer, you can get even more power.

However, that power brings with it a vast amount of experience by understanding how things get done and making sure things do get done. So at the end of the day, you need that experience, but it is also up to the American people to decide when it is time for you to come home.

I remember your farewell speech to the Senate. You said that making hard decisions is why a senator’s constituents sent him to Washington in the first place. In your time leaving office, are there any tough decisions made by a senator or senators that you were particularly impressed by?

John McCain’s vote on healthcare was a thought-through decision. He did not cast any controversial vote without giving real thought to what he was doing. That is the one that stands out in my mind.

I never talked to John about it, but I knew him very well. I didn’t have to ask anyone. I knew John thought he was doing the right thing. At the end of the day, that is what you have to do: make up your mind that your vote is in the best interest of the country.

You and Senator McCain were known for your work on foreign policy and defense. Do you have any particular memories of John McCain that stand out in your mind?

John was such a fascinating guy. I had my differences with John, but we worked through them. I traveled the world many times with John, particularly to Iraq and Afghanistan. John was just an American patriot and a hero in every part of the world we went together. He was so admired, and it was very humbling on my part to be with him when he was honored or recognized by leaders of other countries for his work.

John was just so respected from the perspective of being a world leader.

During his funeral proceedings, the assertion was made that he deserved the title of “statesmen.” In the minds of many, he had passed from being a mere politician to being warranting this designation of “statesman.”

No question John was a statesman. He was no politician, I will say that. Whatever was on John’s mind was what came out, and politicians do not do that very often. He was very plain-spoken, opinionated, and a patriot, all at the same time.

The last question I want to ask you, Senator, is if there is any piece of advice you would most want to give to someone who is running for office for the first time—or is about to be elected to Congress?

What I would tell a first-time Congressmen is that there are certain people you need to watch, know, and emulate. It might be a different person on the conservative side than on the liberal side, but it should be people who have the experience or who are well-respected by their peers. These are people you need to have conversations with, become friends with, and get advice from on a regular basis.

I did that with Senator Nunn. He has always been a mentor to me. He was a Democrat, and I was a Republican. But that did not matter because he was someone I had great respect for. Even after he left, I still took his counsel from time to time. That is primarily what I would tell a young person—or even an experienced person—entering Congress. You need to look to those people who true leaders, who are not on the far-right or far-left. The ones who know how to get things done and done right. That is whom you need to get advice and counsel from.

It reminds of a speech Senator Johnny Isakson gave at the retirement of Senator Cochran. Senator Isakson said that when he was first elected to the Georgia House of Representatives, he was advised to spend his first term observing someone he admired. And that’s what he did. Later when he got to the United States Senate, he did the same thing; and the man he observed was Senator Cochran. He tried to learn from him and let him show the way.

It does not surprise me that Senator Isakson and I would think alike on this topic. Johnny has been my dear friend since our college days. The one thing I truly miss from the Senate is my friends. I don’t miss what they’re doing day-to-day, but you do miss those relationships. My relationship with Senator Isakson was unparalleled. We were the envy of the Senate because we were such good friends, and we always have thought alike. So it does not surprise me that we would have the same thought process, with respect to how you should approach elected office.

And, in some instances, these relationships can extend across party lines?

Senator [Zell] Miller was a person I had great respect for and would seek advice from. It made no difference that he was a Democrat. He was an American first, like Senator Nunn.

I appreciate your time today, Senator.

Very good, Erich. Thank you.