“To tell you the truth, I am drawn to these dangerous events even though they scare the hell out of me. I am sure a shrink would have a field day with that…I guess there is an adrenaline rush in trying to capture images under dangerous situations and making it out alive.”

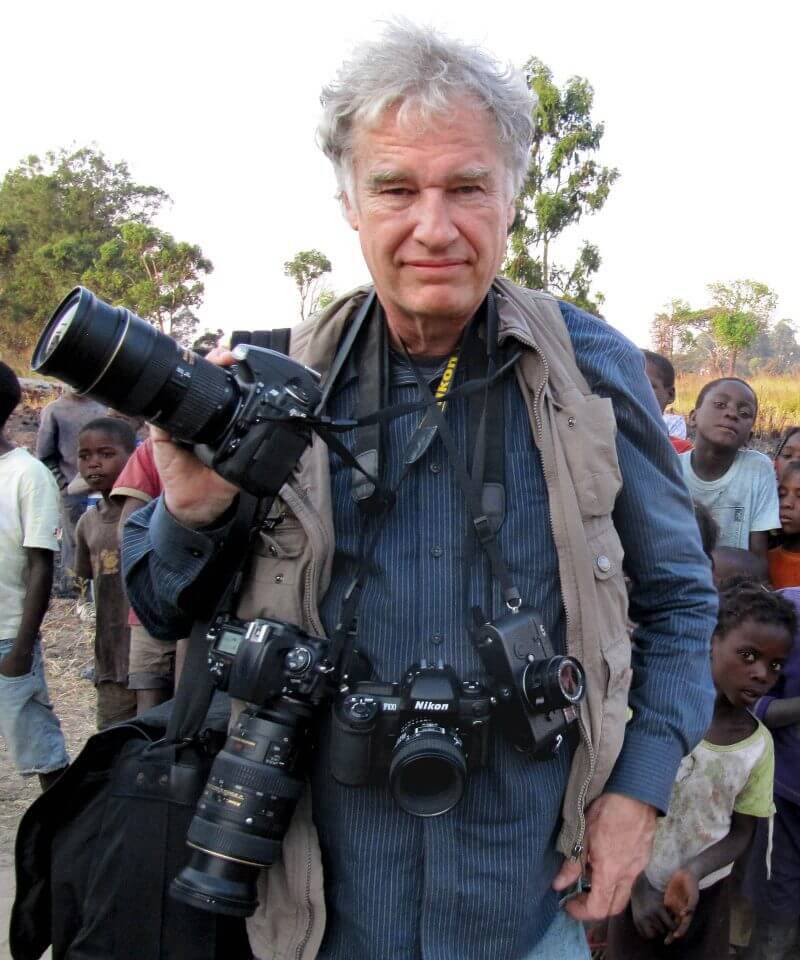

Jeff Widener is an American photojournalist best known for his “Tank Man” image, taken during the 1989 Tiananmen Square uprisings in China. The iconic image of a lone man standing down a column of tanks earned him a Pulitzer nomination, and it would later be selected by Time as one of the 100 most influential images of all time. In addition to covering the Tiananmen Square uprisings, Mr. Widener has also covered major news stories in over 100 different countries and was the first photojournalist to file images from the South Pole. He is the recipient of many photojournalism awards throughout his career, most notably a Dart Award for Excellence in Coverage of Trauma from Columbia University. He is currently based in Hamburg, Germany. On June 4th, he sat down with Merion West‘s Erich Prince to discuss the beginnings of his interest in photography, the psychological toll of photographing tragedy, and the lead up to his world-famous photograph.

You’ve spoken about your first experience, as a child, seeing that Life magazine and the work of Leigh Wiener and how that got you thinking about a potential career in photography. What photographers or photojournalists active today do you think might be inspiring the next generation of photographers coming up?

Magnum photographer Josef Koudelka has been my main inspiration since high school, and I was thrilled to receive a handwritten response to a letter I wrote him a few years ago. Another legendary photographer I was lucky enough to meet was Elliott Erwitt at his New York studio. It’s hard to express how strange it is to meet a legend who you have followed in school and seen in multiple magazine articles and exhibitions and then finally come face-to-face. It can be very intimidating and tends to dramatically reduce one’s self-artistic worth. I think it is something that every photographer should experience because it really makes you reflect on your own limitations and strengths.

In some ways, it may be much more difficult these days to be an influential photographer just because of the sheer magnitude of great images flowing over social media. The brain has limited capacity to digest a single artist’s body of work. The standouts will be masters of self-promotion. I think it was Elliott Erwitt who once said: “To be good, you need to be seen.” Photojournalists Carol Guzy, Michael Williamson come to mind, and their body of work will certainly inspire future photographers.

Can you talk a bit about what brought you to China during the tumultuous events leading up to Tiananmen Square? I recall you mentioning in your interview with Charlie Rose that you were injured badly in the mayhem. How did you persevere through that injury and all that was going on to snap that iconic “Tank Man” image?

Everything starts with an idea. You hear the phrase, “Make your own luck.” At an early age, I wanted to be a combat photographer during the end of the Vietnam War, and I fantasized about following in the footsteps of great war heroes like Eddie Adams and Larry Burrows. But the dreams of a young teen can be a stark contrast to reality.

When I finally had to stand up to the plate during the Tiananmen massacre in one of the most dangerous armed conflicts of my life, I completely froze. There was never a moment following the Chinese government’s crackdown when I was not trembling. It is really hard to explain to someone in the cozy atmosphere of a McDonald’s or Starbucks what it was like to ride a bicycle down a deserted main boulevard—littered with blood stains and smashed bicycles embedded in asphalt by tank treads—as AK-47 gunfire echoed in the back alleys. Imagine photographing a burning armored car as protesters wave steel pipes over a soldier who is curled up dead on the ground. Or how could I explain the sensation of my neck being snapped backward and temporarily blacking out from a large brick that hit me in the face? My titanium Nikon had absorbed the blow, sparing my life. Then, there was the shock of looking down at my destroyed blood-spattered camera, which once held a lens and flash.

There are so many aspects to the chain of events which led me to taking the “Tank Man” photo, but it would literally take an entire book to reveal the magnitude of hurdles I had to overcome. Suffice to say that I was just a very lucky guy, who survived armed soldiers in the street, a massive head injury, and plainclothes security who were using electric cattle prods on journalists. The final dramatic chapter was not knowing whether my flawed execution of a correct camera film speed had ruined the [depiction of an] important moment in history. The June 4th film had to be pried out of the shattered camera in the darkroom with pliers. With all the obstacles in my way, I somehow managed to reach the Beijing Hotel and make the “Tank Man” photo. The film was smuggled past hotel security in the underwear of a college exchange student.

“Tank Man” would appear in papers around the world and is regularly included today in lists of the most influential photographs. Do you find that your photographs ever take on a certain interpretation, political or otherwise, after the fact that you might not have intended them to? Do editors and commentators ever ascribe interpretations to your photos that you disagree with or find to be a stretch?

Media and politicians can spin pictures pretty much any way they want. I admit to sometimes having a little fun with subtle editorializing, and if any photojournalist claims otherwise they are not being truthful. My intentions are more about creating tension in a photo rather than making some political statement. I grew up in the years of Walter Cronkite when journalism was a noble profession. I was taught in school to be a neutral and unbiased journalist. This notion has since evaporated in both the mainstream and non-mainstream media, which is tragic. The left and the right are trying to annihilate each other, and it is tragic. There is no more agreeing to disagree.

I’m thinking of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya’s book Is Journalism Worth Dying For? Final Dispatches. Clearly, some of your work has taken you to dangerous places. Being hit by the brick is one particularly glaring example. How does one process the physical risks of following journalism into dangerous places?

All things considered, I think I have processed things pretty well over my 45 year career, but sometimes the gremlins sneak in like [at] the 2017 G20 summit in Hamburg. There had been mounting anti-government protests going on, and I was trying to be a one-man band, both photographing and filing images to my news agency ZUMA Press. Because I had to edit during the daytime marches, I was missing the action on the streets, so the only time I had for conflict pictures was at night. When I finally had a chance and managed to pass through the police checkpoints and join the riot police, who were facing off with mostly street thugs, I started to pick up really bad vibes.

I was poorly prepared and felt horribly vulnerable without a helmet, body armor or gas mask. My legs got weak, and my heart started really pounding. Something very familiar had taken over me, and I did not like it. My flash in the darkness would make me a target just like my situation in Tiananmen Square many years earlier. Ugly memories flooded back. Just as I tried to process the situation, a shattered beer bottle sent me stumbling in the darkness for safety. The whole situation felt wrong, and I went with my instincts.

It is always a crapshoot with these situations. I was angry at myself for wimping out. I recalled another German photographer who was killed by a rock during a similar protest many years earlier, so I tried to convince myself that safety was the better part of valor. Nonetheless, I made a second attempt the following night and managed to briefly capture images of people running from police as they fired tear gas.

Is there a psychological toll one feels when photographing tragedy or difficult events? Kevin Carter, who won a Pulitzer for his photograph of the 1993 Sudanese famine and later committed suicide, is often cited to this effect. From the Seton Hall dorm fire series to 9/11’s “The Falling Man,” many of the most iconic photos are photos of tragedy. Does photographing these events weigh on the photographer or is there some relief to be found in showing these unpleasant happenings to the world?

To tell you the truth, I am drawn to these dangerous events, even though they scare the hell out of me. I am sure a shrink would have a field day with that, but I am not the only newsperson out there who feels this way. I guess there is an adrenaline rush in trying to capture images under dangerous situations and making it out alive. I am probably more scared thinking about going back than actually being in the thick of it; your mind goes into a weird comforting defense mode when you are in hell. At my age, these stories are not easily doable, but that does not stop me from contemplating future dicey news events. I have never been depressed or suicidal, though I have heard confessions from other photographers about it, and some have actually gone through with it.

Obviously, the “Tank Man” photograph is the image you’re best known for, but what other photos that you’ve taken do you think are particularly significant or important that people ought to take a look at?

Many iconic photographers are one hit wonders. You never see their other body of work. This is why I started posting my other pictures on Instagram, and it has been a lot of fun. People can judge for themselves whether I have anything to offer. I do think it is safe to say, though, that I will probably be remembered more for the “Tank Man” moment, and that’s okay.