“I want to tickle a certain part of your brain, a thinking person’s part of your brain. We don’t really like giving answers on our podcasts. I ask questions.”

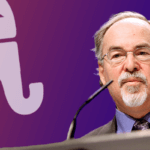

On April 12th, podcaster and historian Dan Carlin joined Merion West to discuss his unique approach to studying history, the transition from traditional radio to Internet broadcasting, and the future for how people consume history.

Thank you for joining us today, Mr. Carlin. To begin, what were the major factors that influenced your transition from radio to podcast and internet broadcast?

Well, radio was starting to suck, for lack of a better word. The difference between what it was like to be in radio when I started and what it was like when I was at the end stages of doing it was like night and day because the laws had changed.

When I first started in radio you couldn’t own more than a few radio stations, so most radio stations were owned by small time management people that were probably in the building with you. So you could literally talk to your boss if you wanted to. The people that were working at those stations were unique employees that were tied to the community because the station owners lived there.

Then in 1996 I think, there was something passed called the Omnibus Telecommunications Act, and one of the things it did was lift those requirements on how many stations an owner could own. Very quickly, three or four giant corporations bought almost all of them. You’d have Clear Channel or Cumulus with nine hundred radio stations. All of a sudden, if you were at one of those radio stations, things got a lot more cookie-cutter. You were taking orders from some program directors states away, who were trying to program hundreds of stations all at the same time.

It just took all the creativity, fun, and uniqueness out of it. So I’d already been approached years before by somebody who was talking about what they called ‘Internet radio’ back then. So the seeds had been planted. More and more opportunities were coming to jump ship and try to make that dream (a dream that goes all the way back to 1995) a reality. Once things got bad enough in traditional radio, it made it easier and easier to contemplate some radical move like that at the time.

Can you elaborate more on what you mean when you describe your new ‘prudentist’ approach to politics and current events?

Nobody has asked me about that for a while. I was trying to come up with a name. I was always really jealous of those people that could tell you everything they believed just by giving you a label; you were instantly introduced to everyone in the room if you could say “I’m a liberal Democrat” or “I’m a conservative Republican” or whatever it might be. Like many Americans, I seemed to be so many different things. I didn’t know how to wrap it all into one label, so we started playing around asking what sort of label represented people who thought like us.

The one thing that I’m always hoping for andand that I think a lot of people think is missing in our system, is wisdom. So I try to think of a term that implied a greater level of wisdom than we bring to things like politics and leadership today, and the word that I kept coming back to was prudent.

Neo-pragmatist actually sounds better because it sounds like a real thing. “He’s a neo-pragmatist!” But pragmatism seemed to me to allow for people to act in short-term interest, like it might be pragmatic to take over these oil fields right now because we’d make a lot of money. But is it the right thing to do two generations from now? Well, that would be a more “prudent” question to examine. So that’s kind of how we went to neo-Prudentist because I think wisdom used to be more of a commodity than it is now, so we’re not like the old prudent. It’s a return to an attempt to inject more wisdom into the conversation.

I wanted to ask you about your podcast on the Greatest Generation, which asks questions about how certain conditions might create tougher people. Can you speak a little more about what you were discussing in that episode?

We did a show where we focused on the question of toughness because it’s a strange sort of question for historians to try to deal with today. So, for example, if I go back and read ancient Greek writings and they’re talking about the Spartans, they’re going to say in one adjective or another that these people were defined by their toughness. But what does that mean?

It’s obviously something the contemporaries consider to be important. We can recognize that as a human trait on an individual level. I can say Dave is tougher than Joe and explain why I think that. But can countries be tougher than other countries? What would the criteria be?

For example, if you wanted to decide that, yes, the Spartans are tougher (and we know this because all the evidence from history says that they were tougher), then you have to ask how do you quantify that? Do you say they’re tougher because all the other Greeks thought they were tougher? So then the next question is: how tough were the other Greeks. Maybe they were all wimps, and the Spartans were just the toughest people in the region.

It becomes this extremely hard human element for experts today to deal with because there’s no way to quantify it. There’s no evidence you could point to that’s unbiased. There’s no good way to make use of that fact, and yet it’s one of those things that seems to have played a key role in history. If there is something like toughness, how does one get it? Do tough times make tougher people? If you go through the Great Depression and you have to learn to save every penny, are you tougher than a generation that gets raised in luxury?

The funny thing is that these were ideas that earlier historians used to talk about as though they were laws of history. They’re called tropes because they’re so commonly brought up, so modern historians spend a lot of time shooting down those tropes because they recognize how ridiculous they are. But, at the same time, there’s still that little kernel of interesting truth somewhere in there.

Is one group of human beings tougher than another group of human beings and what sort of difference does it make? So, for me, that toughness question sort of encapsulates all these wonderful unanswerable questions that belong in some discipline, and history just seems the best fit. It’s easy to identify in individuals; it’s a lot harder to say Venezuela is tougher than Ecuador. I mean what would you use for evidence, right?

Certainly an interesting new conception of how we might conceive of “toughness.” So what is the future for how people consume history? You’re on the cutting edge of new patterns in how people today learn about history. Have books been overtaken by audio and visual media?

I don’t know and I’m not the best person to ask because I’m a book fanatic. I like the touch, the feel, and the smell, even the print that was chosen, so I’m a nut that way, I’m almost a collector, so my family is still trying to get me to use digital book e-readers. I won’t touch it because I’m old school. So in my weird warped way of thinking I feel like if people are not consuming as many books as they used to, that’s more books for the rest of us.

I don’t know how they consume their history. I think at ground zero, history comes from the books. When we start looking stuff up to form the information for our audio production or our visual production, but somebody is picking up a book somewhere. So I would suggest that even if in the chain of supply, more people are actually consuming a finished product that’s an audio or visual product, somewhere in the chain somebody is reading the original material to come up with facts to use in that audio or visual reformatting, repackaging of the real information. One way or the other, I think books are safe. But, again, for people like me, I have to have the information in my hands, so I’m not even qualified to answer this question. I might just be too old!

Is it possible that some people might be relying

I think that’s a useful point to make. If you want to get into the whole fake news question and which media do you believe, I think studying history is subject to the exact same need for vigilance. This is true for interpreting the correctness or accuracy of information that’s coming to you.

If you’re asking whether people possibly rely too much on a podcast for their historical data: well, absolutely. But on a lot of these subjects that I’m researching―for example, I’m reading history books, which disagree with each other, and that’s a good thing. But it shows that in history, the concept that there is a right answer is flawed from the get-go. History is just the reality of the past. If you look at reality now and ask someone to give you the right answer―well, that’s an opinion question, isn’t it? The reality of the past is the same way. So my answer would be, even if you’re relying on a book, you shouldn’t rely on one book. You shouldn’t rely on one point of view in one book. If you really want to understand an issue, you need to look at it from multiple viewpoints. The best way to do that is to grab a couple of books, which disagree with one another. Same with podcasts.

Lastly, what do you hope listeners

I want to tickle a certain part of your brain, a thinking person’s part of your brain. We don’t really like giving answers on our podcasts. I ask questions. I ask the sort of questions that speak to humanity because history is human history, after all. I always compare it to how we’re a bunch of lab rats, and human history is like a laboratory.

What do the lab rats do when you put them in various situations under different kinds of pressure, in different kinds of societies, with different kinds of cultures. How do we react, and what are the extremes of what you can expect? What’s the shyest we could be? What’s the most obnoxiously loud we could be? What’s the most sedate-looking we could be versus what’s the wildest-looking we could be?

These extremes are the range of human behaviors. So if we do the questions correctly without any answers at all, we can get you thinking about what it means to be human and touch a nerve. For example, a little earlier, we talked about that toughness question. There’s no answer to that question. But, if you think about it long enough, it’s a fascinating discussion.

Does toughness change anything in the outcomes―or is everything the same in the end? Does modern warfare eliminate any advantages that toughness used to offer when it was just about who could sock each other in the face harder? Those are interesting questions that prompt other interesting questions that don’t necessarily have any answers. So, when you say what do people take away from the show, I like to think that when we do a good job, we ask these questions that are intriguing enough so you walk away thinking about them.

Hopefully, they’re still interesting when you think about them later. We say at the beginning of hardcore history: the events, the drama, and the deep questions. The deep questions are all those unanswerable things about what it means to be human. The answers are not necessarily why you’re asking the questions, simply wondering sometimes what it means to be human prompts a self-introspective sort of examination that tells you more about ourselves than you would if you didn’t ask the question.

Thank you for joining us, Mr. Carlin. It was a pleasure having you.

Thanks for having me.