“I’m a Vietnam era veteran myself. The stigma of suicide today is only a fraction of what it was back then…Times are changing, and we are trying to meet those changes to get people taken care of in a timely way.”

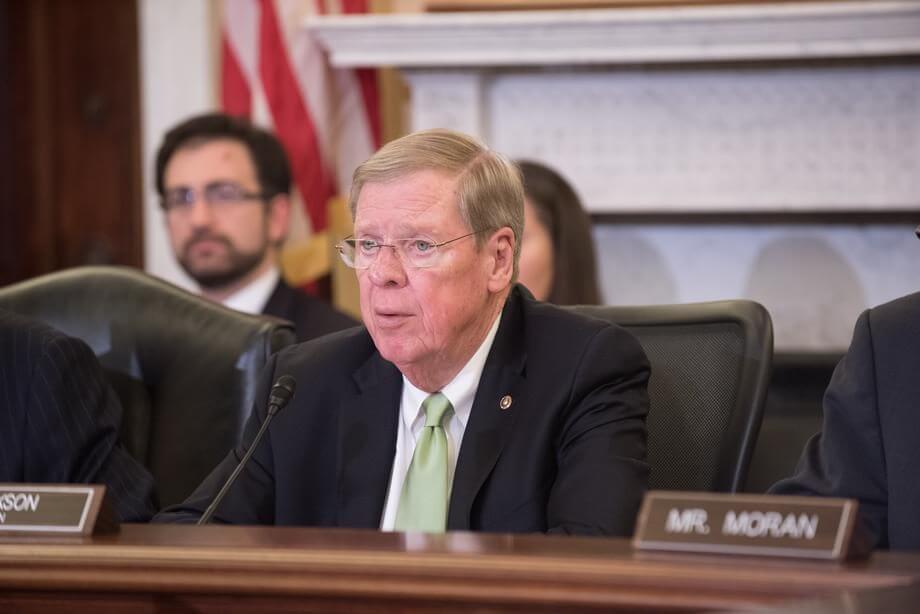

On April 16th, U.S. Senator Johnny Isakson (R-Ga.), who is also the Chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, joined Merion West‘s Erich Prince to discuss issues facing veterans today and his efforts to combat suicide and opioid abuse among those who have served the United States in uniform.

Senator, good morning. Very nice to hear from you, and I look forward to chatting about issues affecting veterans, an area of particular advocacy for you. So to start off and set the scene, I want to ask you about your op-ed last Memorial Day in the Savannah Morning News.

You describe this very moving experience of walking among the headstones and noticing the grave of a soldier, who was killed on the very day that you were born: “All of a sudden, the meaning of Memorial Day became clear. On the day my mother gave me life, Roy C. Irwin sacrificed his life for the freedom I have enjoyed and cherished for 72 years.” What are some of these moments that help remind you of the sacrifices our veterans make?

I think that we, as Americans, take for granted so many things that we have and that we treasure. Some of these things we have only because our veterans fought and, in some cases, died so that we have them. That was just a good example, a very moving moment and a moving incident in my life. I was at an American cemetery, where the soldiers from the Battle of Bulge were buried, and I was going down looking at the headstones. My wife was with me. We came to one, and we saw December 28th.

We stopped because that’s my birthday and looked at it. It was Roy C. Irwin from New Jersey, who was killed in the Battle of the Bulge on December 28th, 1944, which is the day I was born in the United States of America. While he was giving his life for the country, I was getting life at a hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. But there are many things we take for granted in terms of liberties that we enjoy that we get solely because soldiers risked their lives to be able to give these to us. So I always use this story to make that point.

I’d like to ask if you can elaborate a bit more on your plan to combat opioid abuse by veterans, including your specific proposal to “hold the VA accountable for over-prescribing.” How can we consistently ensure that the VA is following proper protocols when it comes to dosage and choice of painkillers?

We are implementing them. Some of them have been recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), by the National Institutes for Health (NIH), and by others. I’m on the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, and we are in the process of introducing next week or this week a comprehensive opioid bill. There is nothing more timely. 63,300 people died [from drug overdoses] last year in America, and that number is only going up every year. Every one of those deaths is avoidable. People need to break the habit and get off the opioids. We have to stop playing games with opioids and get to the source: and that is treating addiction, which is the main root cause of it. We need to limit the accessibility [of opioids].

In terms of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), as a chairman, I’ve backed up Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin and others, including Speaker Paul Ryan on the House side, also from the state of Wisconsin. The Tomah VA Medical Center [in Wisconsin] actually turned out to be giving out opioids as painkillers for soldiers who were being treated for other problems. But the opioids were actually contributing to the problem. They were just being used as a passing painkiller, like an aspirin, Tylenol, or something like that. But, in fact, it has addictive properties that are stronger than any aspirin ever had.

We replaced certain doctors. We replaced the director [of Tomah VA Medical Center]. We sent out a directive to all of the VA hospitals and clinics around the country about the CDC recommended protocol on prescribing opioids in the first place. We are doing everything we can to limit access, except for in times of actual need—not as a casual painkiller. Also, we are better educating both the patients and the doctors about the tremendous damage that opioid addiction can cause.

Along similar lines, when it comes to mental health issues among our veterans, in your Caring for our Veterans Act of 2017, which specific efforts are you most confident will help address mental wellness and suicide rates among veterans returning from conflict zones?

That’s a great question—because, in terms of mental health and, particularly, in terms of suicide, timing is everything when it comes to stopping that from happening. When someone is at risk to take their life, you don’t have much time to get to them, to counsel with them. You don’t have much time to be accessible. We have to, first of all, do a better job of keeping our mental health services accessible to our veterans. To that end, we’ve done that in the past year by establishing three hotlines around the country. One of them is in Atlanta, which is no longer manned by a machine.

We [previously] had some hotlines that were manned by machines, which were saying: “We’re too busy to take your message.” In the case of a suicide attempt, ten seconds is everything. You want to be able to talk to somebody at all times, anytime you need them. We’ve done a good job of bringing in people in those settings to answer those initial calls to get the veterans stabilized. In some situations, we can get them to doctors or physicians in a hospital.

We are having a significant impact in terms of veterans coming into the VA for counseling and then staying in a program to deal with their suicidal ideation—rather than having them run the other way. Accessibility is everything. Our hotlines have a link on our telemessaging where they can talk not only to the individual who answers the phone at the hotline; they can also go to a specific doctor that they have been talking to or working with. We’ve done a lot to remake the veteran’s ability to select a doctor and find a doctor more easily. In concert with the VA, we’ve made it easier for veterans to find a doctor in residence to work with them on their recoveries.

It’s all about timing. It’s all about accessibility. Just like if you’re doing surgery, the more operating rooms you have, the more surgeries you can do. The more doctors and psychiatrists you have, the more people with neurological or clinical challenges—and the more people with a tendency towards suicide or mental health problems—you can help.

We’re trying to explore every way we can to expand access to your veterans to qualified medical care, all on a phone call basis.

Are there any policies that you are pursuing to encourage veterans to seek treatment by reducing the stigma around mental illness and suicide? Clearly, if all these resources are available, how do we make sure veterans are going to, in fact, take advantage of these resources?

Your question is an excellent one—because the stigma of suicide is a twofold problem. One, the veteran has a stigma on himself or herself. Second, society takes a negative look and not a clinical look at suicide. Suicide is a byproduct of mental health problems and disease, which are treatable.

The first thing is that we need to make everyone understand is that this a treatable condition that anyone is subject to, if the wrong circumstances happened to them—number one. Number two, the timeliness of getting them to talk to or work with someone is critical. Many times, privacy is critical as well. In our VA hospitals, in our clinics, in our warrior transition centers in our bases, we have question-and-answer sessions on mental health with a computer—so they are not talking to a human being. So there is not that stigma where they think: “I don’t want this person thinking I’m crazy.”

They’re answering questions that are being fed to them by a computer, so they are a lot more honest and forthcoming. We have learned a lot of the triggers that help direct us towards early diagnosis of someone who is potentially suicidal.

Given some of these new programs now in place, do you think it’s easier now for veterans coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan, as opposed to those from the Vietnam era?

No question about that. I’m a Vietnam era veteran myself. The stigma of suicide today is only a fraction of what it was back then. You couldn’t get a soldier—or anybody—to talk about suicide at all. Times are changing, and we are trying to meet those changes to get people taken care of in a timely way.

For the last question, in November of this past year, you and Senator Ed Markey (D-Ma.) introduced a bill to honor certain World War II special forces. Also, around that time last year, groundbreaking took place for the new World War I memorial, long-awaited by many. Are there any current efforts to honor veterans of wars past and present that you are particularly proud of—or speak to what you were talking about earlier: making the public aware of the sacrifices veterans make?

I appreciate the question because I am sitting in my office looking at a collage of six photographs of American cemeteries in Europe that I took when I toured the American cemeteries there. I’m in the process of trying to visit every American cemetery by the time my term is up in three years, as chairman [of the United States Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs].

If you ever go to an American cemetery, under the Veterans Administration’s care, it is absolutely pristine, absolutely immaculate. It is a beautiful place and a real tribute to the care we have for our veterans and those who sacrificed their lives in war.

I’m going to work on everything we can do to make sure that when someone is interred in a U.S. veterans’ cemetery, they have every accommodation they should. Most recently, we have two cemeteries that are American veterans’ cemeteries that are not run by the Veterans Administration; they’re run by the Park Service. The Veterans Administration makes sure that every grave has a grave liner. They don’t do that at the Park Service. We are now supplying the Park Service with grave liners for any veteran’s funeral that goes through their cemeteries. This is just to make sure there is absolute equal treatment for every casualty, for every veteran.

If you visit our Georgia cemetery in Marietta—or also our Georgia cemetery in Canton, they are beautiful cemeteries. They are beautiful places that are a real tribute to the men and women, who honored us by fighting and dying for us. They are also a tribute to our country for taking care of them.

I continue to make those cemeteries not only places where you go to reflect—but also monuments to our soldiers and those who sacrificed everything. We continue to work on things like the National Infantry Museum at Fort Benning—a great facility. We’re working on the changes at Fort Gillem with Fort Mac [Fort McPherson] being surplused out at the last round of the Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) and Fort Gillem remaining in the full ownership of the Army and the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory. We’re continuing work to improve that and doing everything we can to invest in our CBOC’s, our community-based outpatient clinics.

I went to Macon, Ga., in March and opened another one. So we have our CBOC’s, and they are closer to our veterans when they are in need. The bottom line is to establish mental health care for our veterans that has close proximity [to our veterans] and with quick access to clinical psychologists and caregivers.

The last thing is on caregivers. I have said it publicly in Washington, and I almost delivered a month ago. I want to see to it that we have caregiver benefits for all era veterans as soon as possible, which means that those loved ones: cousins, wives, spouses, family members caring for veterans at home have part of the benefits that post-9/11 caregivers have. We need to support those being cared for in every way.

Thank you for your time this morning, Senator―very interesting perspectives, so thank you.

Have a great day, and thanks for calling.